If you are middle class and lately feel like you’re not getting ahead, you’re not wrong. The economic facts bear this out. The middle class household is taking home about the same in inflation-adjusted dollars after taxes today compared to their income in 1971.

According to the U.S. Census, in 1971 the median household income (the households in the 50th percentile, the middle-est of the middle class) was $9,030. Adjusted for inflation using Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers for the Consumer Price Index, that’s $67,394.56 in December 2023 dollars purchasing power. By 2023 that median household income number had increased to $74,202.00, about a 10% increase over fifty-two years.

It’s a little improvement, right?

Not really.

Federal taxes have increased significantly on middle class Americans since 1971. While income taxes are slightly lower and other federal taxes slightly higher, the real difference in federal tax burden is the increase in payroll taxes by nearly 50% since 1971.

The payroll tax for Social Security and Medicare on middle class income in 1971 was 10.4%, or $7,009.03 in current dollars for a median household, while it has since increased to 15.3%, or $11,352.91. After deducting the additional payroll tax, middle class families are only taking home about $2,500 more in purchasing power than they were in 1971 ($60,385.53 vs. $62,849.09). That’s a less than five percent increase over more than five decades. It should be stressed that the payroll tax is a tax only working people pay; real estate developers and hedge fund owners generally don’t pay a dime of it.

The median worker in America may actually be taking home a little less in purchasing power than the median worker in 1971 after accounting for state and local taxes. The Tax Foundation reported back in 2000 that “State and local taxes combined took 8.8 percent of the two-earner family’s income in 1975, but 23 years later that share had grown to 13.1 percent. For the one-earner family, state and local taxes make up an even larger share of the total tax burden and have been growing even faster. In 1975, state/local taxes took 9.4 percent of family income, but in 1998 they took 15.0 percent.” The trend since that 2000 report has not been a decline in state and local tax burdens, but if anything a modest increase.

The median worker, that middlest of the middle class, hasn’t gotten ahead since 1971.

And this measly 10% increase in gross pre-tax pay over the past five decades happened during a time the workforce became much better educated; the percentage of working age people with high school degrees increased from 60% to more than 90%, and those with college degrees has more than tripled since 1971 from 11% to 37%. You’d think that would be represented with higher median income levels, but you’d be wrong. The past five decades have also been a time of rapid increase in two-income households since the 1970s, when only the father generally worked outside of the home. Here also you’d be mistaken to think that more of both parents working have increased middle income earners’ take-home pay.

Meanwhile, America as a whole has been getting richer. The real (Consumer Price Index-adjusted) per capita production in the United States increased 154% between 1971 and 2023, from $26,515.87 to $67,547.23. And working people got almost none of it, even though they were getting the majority of the gains up until 1971.

The 1971 Economic Report of the President to Congress reported that from 1946-1970 output per man-hour increased 2.4 times, but hourly compensation in the form of wages increased 3.4 times over that same time period. That 3.4 multiple increase in hourly wages represents an after-inflation increase of more than 50% in real (inflation-adjusted) terms in just twenty-three years, in contrast with the meager 10% increase in family income over the more than fifty years since 1971.

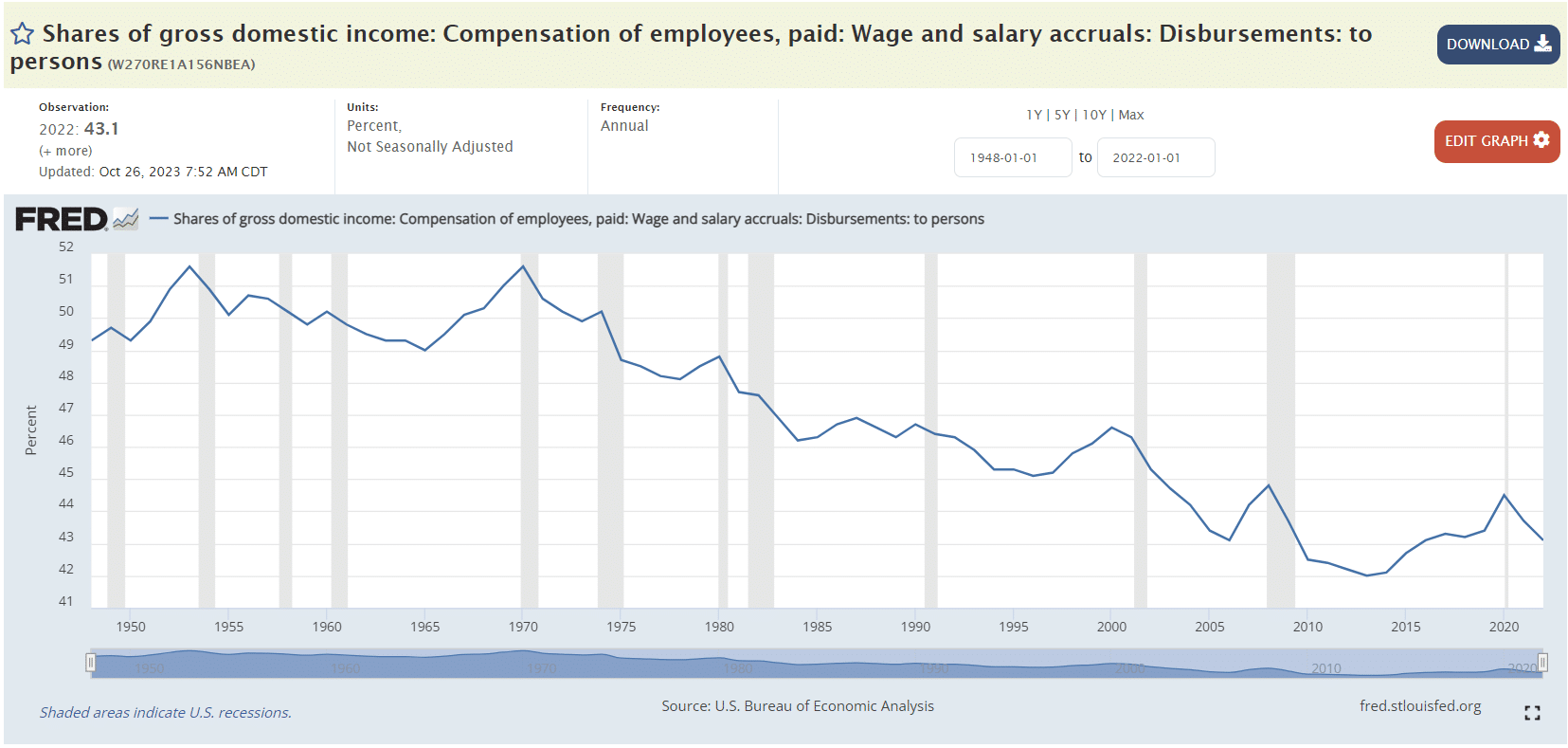

In other words, American workers’ wages have continued to increase, but only at one-tenth the rate of the early post-war period, and all of those gains have been taken from middle class workers in the form of higher payroll and state/local taxes. Not surprisingly, since its 1971 peak, wages as a proportion of Gross National Income has reliably declined from an all-time high of 51.6% down to 43.1% in 2022. The U.S. economy as a whole, both in real and real per capita terms, grew much more slowly after 1971 than the two and a half decades before 1971, with the chief difference in that growth rate being the stagnation of the bottom 90% of income earners.

The continued increase in national wealth in the United States, and to a lesser extent in other Western nations, without a proportionate increase in the wealth of middle and lower-income families has been called the “great decoupling” by social scientists.

The symptoms of the “great decoupling” have been economic stagnation of the middle and lower classes, a moderate increase in the wealth of the top 10% of income earners, explosive growth by the top one percent, and especially the top 0.1%.

Many free market economists fall into the trap of using the “average” income as a metric to tell working people they’ve never had it so good. Most working people know better from their own checking accounts, however, and it’s important to make the distinction between average and median. In an economy of ten people, nine making $1,000 per year and one making $11,000 per year the average is $2,000 per year while the median (the middle income earner) is $1,000. If the top income earner next earns $991,000, the average increases to $100,000 per year, but the median income remains at $1,000. That’s an exaggerated view of what has happened in America since 1971 where the median and the average with respect to incomes have diverged.

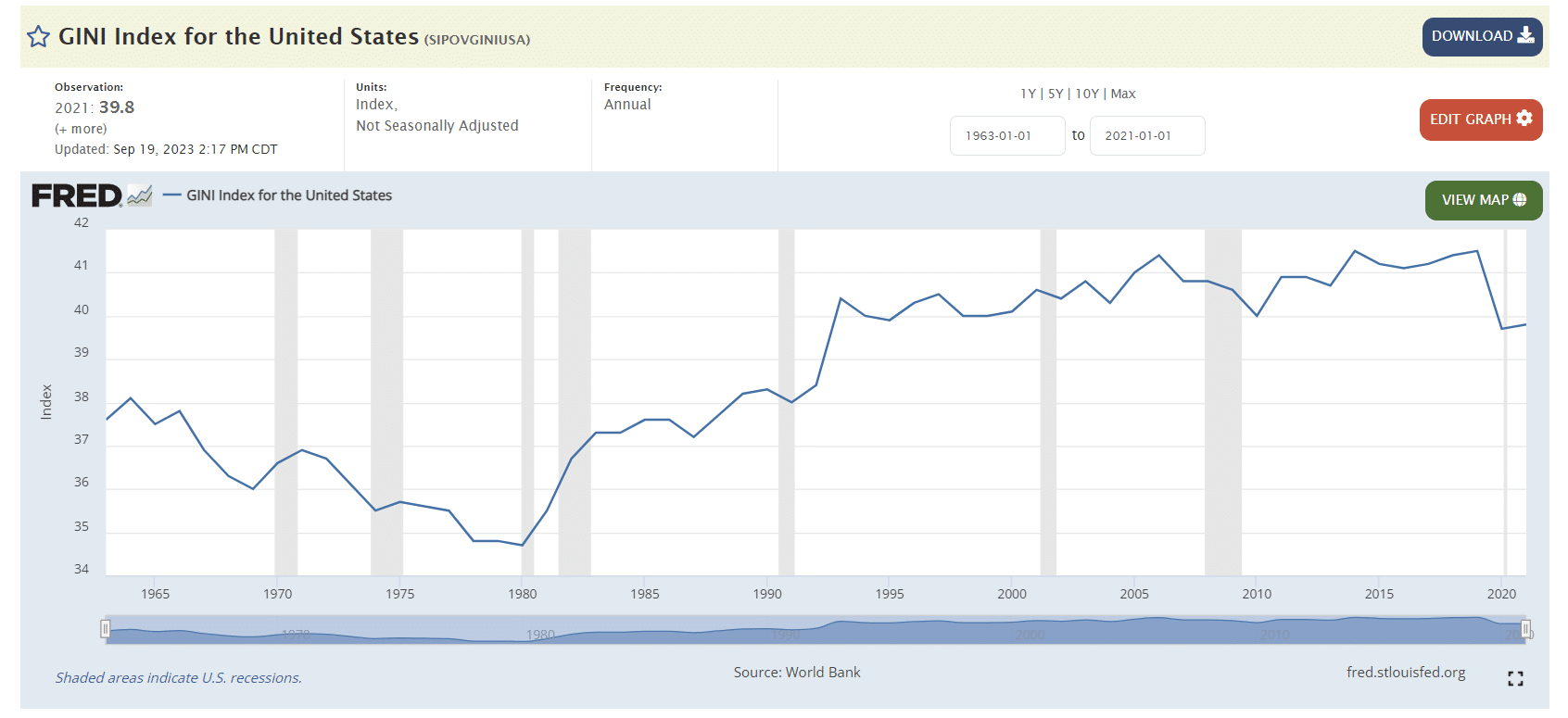

The GINI index, which shows the difference between perfect income equality (0) and perfect inequality of income (1, or a single person owning all the wealth), continued to decline until 1980, despite the beginning of the trend toward a reduction in the proportion of national wealth going to labor. Part of this 1971-1980 trend can be explained by the lower real (after inflation) value of the stock market during that time.

The political left likes to attribute this change in income proportion to Ronald Reagan’s tax cuts and the non-existent economic philosophy of “trickle-down economics.” But unless President Reagan received powers to go back in time and start the impact of his 1981 tax cuts a decade earlier (they actually didn’t have an impact until 1982), it wasn’t cutting taxes on the rich that stymied the then-ongoing economic progress of the middle and lower class.

Moreover, while lower income taxes on the rich might conceivably explain faster wealth accumulation by the rich than in previous decades by allowing them greater opportunity to invest more, it doesn’t explain why the lower and middle classes stopped gaining economic ground.

Another reason some of the super-rich might be getting richer is the opening of the global trade market and the general removal of tariffs globally with the Kennedy and Tokyo rounds of GATT (which took effect in 1968 and 1981, respectively), adoption of NAFTA in 1994, and the WTO in 2000. Under the tariff-based national system, if a businessman sold a product to one-third of Americans for a one dollar profit, he’d have a little over $100 million. But today someone can sell a product in the same way to one-third of the world population for a dollar profit, where he’d earn about $2.5 billion.

But like lower taxes, while freer global trade might explain greater economic progress by some of America’s rich businessmen, it doesn’t explain why the poor and middle classes haven’t also benefited directly from this global trade. Global inequality of incomes has actually been falling for the past five decades, as extreme poverty in many emerging economies like China, Eastern Europe, and India have been dramatically lifted upward.

One key factor already alluded to above that explains the stagnation of middle and lower class working people in the United States is taxation. As noted above, higher payroll and state and local taxes on working people has a direct impact upon their take-home pay and negated all the progress they made since 1971 in the form of wage increases. But it may have greater downstream impacts as well. Lowered income from taxation may limit the ability of working people to save and invest, which are the keys to economic growth.

If the left is going to claim the rich are getting richer because the tax rates on their income was cut, doesn’t it also stand to reason that higher taxes on working people’s incomes explains the stagnating incomes of the middle and lower classes?

The “bi-partisan” agreement of Washington DC of our lifetime has been to keep taxing labor at nearly twice the rate of capital, and keep raising prices on working people through forever-inflation. Both the Democrats and Republicans agree on that.

Democrats think if we keep punishing taxes and inflation on the working poor and also enact more punishing taxes on the rich, the poor will get richer. In essence, Democrats are saying “If I keep punching the jaw of a poor man every day, but punch the jaw of a rich man daily as well, the poor man’s jaw will heal.”

Republicans think if we shift more of the tax burden to the poor by cutting taxes for the rich, the poor will get better. In essence, Republicans are saying “If we keep punching the jaw of the poor man every day, and only punch the jaw of the rich man once a week instead of every other day, the poor man’s jaw will heal.”

But they both agree that the poor man’s jaw must be punched every day.

Perhaps the biggest factor arresting working people’s economic progress is the most regressive tax of all: inflation. The economic timeline is spot-on; inflation, while it started to increase in the late 1960s, really got going when the U.S. government severed the final tie of the dollar to gold in 1971 with Richard Nixon’s closing of the gold window.

And inflation is “wage theft.” Inflation taxes a working person’s wages twice, after he does his labor while he is awaiting payday, and again even after he deposits his pay into his checking account. Only when the worker finally spends or invests his wages in commodities other than dollar-denominated bank accounts does inflation stop taxing working people.

But inflation leaves the rich man’s yacht untaxed. No level of inflation, no matter how high, can take one cent of value away from a yacht. A yacht is always going to be a yacht, no matter what the value of money is. Moreover, inflation actually benefits debtors like real estate developers who take out mortgages on properties they purchase. As inflation cuts the value of debts and cheats creditors, mortgage debts owed by real estate developers and financiers get easier to pay off over time.

Wages on the other hand are almost always a social credit. Laborers do their labor and usually wait a week or two to get their pay. Wages are almost always the largest debt line on every company’s account, and as already noted above, are a social credit still accounting for more than 40% of national income, or more than $10 trillion in the U.S. economy.

In essence, all the poor working man has is his labor. It’s his only asset, and inflation takes it from him and gives it to the real estate developer and the hedge fund owner on Wall Street. Inflation hurts those with the least the most, and those with the most the least.

Because the proportion of wages in national income was more than 50% in 1971, the introduction of more dollars into the economy must dilute the value of wages because wages are necessarily denominated in dollars. Rich people can avoid the inflation tax almost entirely by putting their wealth into inflation-proof, non-dollar-denominated assets like stocks, real estate, and commodities. The working man (and woman) is the one person who cannot defend himself against the inflation tax because the social construct always prevents him from getting an advance on his wages. Thus, it should be no surprise that the value of wages as a proportion of national income has been reduced over time as the money supply has increased.

Price stability is essential to wages increasing. In 1913, $20 in weekly wages was enough to live a comfortable middle class life. Today, that $20 gold coin the laborer earned is still enough, with a melt value of about $2,500. But every constant downward change in the value of the dollar because of inflation has to be negotiated between laborers and management, and that takes time. And during the modern time of constant inflation-adjustment negotiations, labor is continuously losing ground and playing a game of catch-up.

Yet forever-inflation of 2% or more per year is the declared policy of the Federal Reserve Bank and U.S. Treasury officials. Jerome Powell’s Federal Reserve Bank only says, as it did in its September 18 interest rate decision, that, “The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run” because saying “we want to give workers a 2 percent pay cut this year and another pay cut next year of 2 percent on top of this year’s pay cut” would be too obvious.

The middle class disappears almost entirely in nations with very high inflation. The more than 100% inflation rate in Argentina last year caused a huge surge in the number of people back down under the poverty line. Likewise, a decade ago Zimbabwe’s middle class was devastated by hyper-inflation, a prospect that has come back to that country which was relatively prosperous by African standards in the 1980s and 1990s. In America, inflation hasn’t been quite extreme enough to destroy the middle class like it has in Zimbabwe, Venezuela or Argentina, but it has had enough of an effect to stagnate the middle class.

The “great decoupling” as a global phenomenon can also be explained by inflation in a way that Reagan’s tax cuts can’t possibly explain the global phenomenon: The world economy has been tied to the dollar as the global exchange currency, under the Bretton Woods system after World War II where the dollar was tied to gold at $35 an ounce, and since 1971 by the petro-dollar. The inflation of the dollar, along with its impact upon working people, would have global effects in a way that Reagan’s income tax cuts could never have.

Working people need a fair shake, and the American people need to end the plundering of them by Washington now, while there is still a middle class left to save. And that means putting a stop to inflation by ending the Federal Reserve Bank and cutting taxes for working people.