Civil rights do not fare well in wartime, tested against the feverish jingoism of the martial spirit. As the old adage goes, inter armas silent leges — in war the law is silent. In the United States, liberty has too often been sacrificed (without hesitation, we might add) to the gods of wars, forced to prostrate herself before them, accede to their demands. But never completely is liberty’s light extinguished; undaunted and filled with righteous indignation — and, perhaps, naivety — a few idealists always stand as her partisans, prepared to sacrifice their own liberty in their own kind of war.

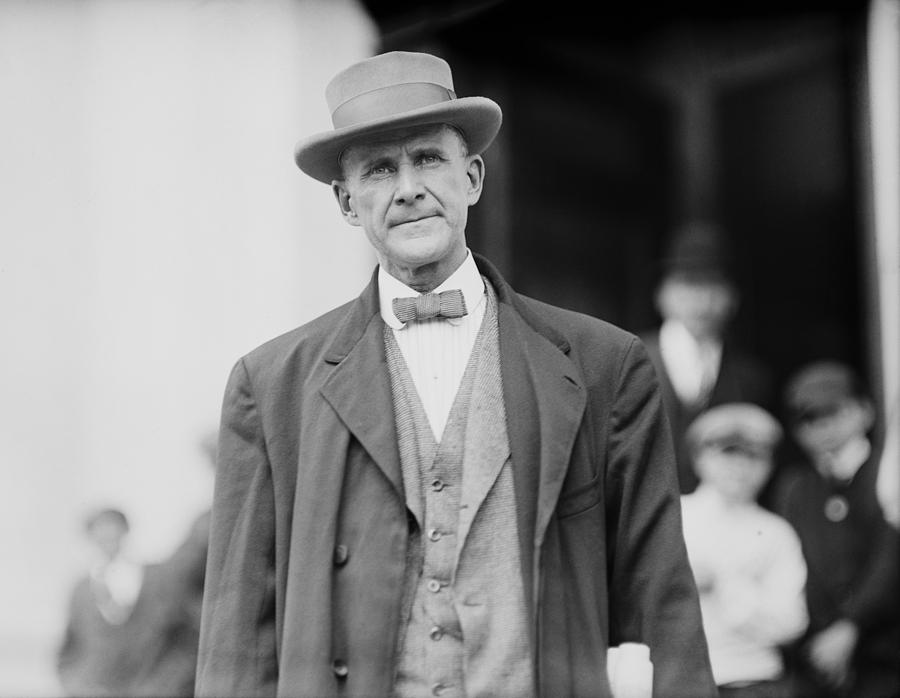

Eugene Debs, whatever his faults, was one of this kind, a true believer. He was born in 1855 in Terre Haute, Indiana, a town west of Indianapolis and near the Illinois border, the son of immigrants from the French region of Alsace. Far from steeping the young Gene Debs in left-wing radicalism, his parents owned a small grocery store and led a quiet life devoted to their many children. But Debs was curious, compelled toward literature, debate, and the world of ideas. From humble beginnings, he would go on to become, in the words of Max Eastman, “the spiritual chief and hero of American Socialism,” but he is important to the libertarian tradition, too, as a symbol of free speech. His trial in 1919 represents a travesty of justice, an egregious affront to the individual’s inviolable right to speak his mind. It also speaks to the fragility of mere words on a page, confronted with the power of a growing modern state in the hands of Progressives. Woodrow Wilson’s administration embraced centralized government power enthusiastically, seeing in it an expression of the true social organism.

Passed the year that the United States entered the fray in the Great War, the Espionage Act of 1917 was one of several successive attacks on liberty and the constitutional order during Wilson’s presidential tenure. Lest the title of the law cause confusion, it addressed itself both in theory and practice to a range of activities that few would readily associate with spying. Together with the Sedition Act, an addendum passed the following year, it gave the federal government broad discretion to prosecute virtually any speech critical of the government or the war. Under the statute’s vague, overbroad language, even the faintest criticism of U.S. participation in the war could be considered an attempt to aid the country’s enemies or otherwise hinder the war effort.

It was to this draconian law that Debs, outspoken in his anti-war convictions, eventually fell victim. Intellectually and morally abased by the hysteria of war, the American political and media establishment could conceive of no way one could be so unreservedly critical of the war without also being “an agent of a foreign power.” Distrust of foreigners in general reached new heights. The war rendered the nation amenable to the most extreme public-policy expressions of nativism and anti-immigration sentiments, already, in the words of Thomas C. Leonard, “a chronic, debilitating illness” in American public life. German-Americans, widely treated as a presumptively suspect other, were now the subjects of sweeping registration requirements, with thousands interned at camps across the country.

Read more at the Future of Freedom Foundation.