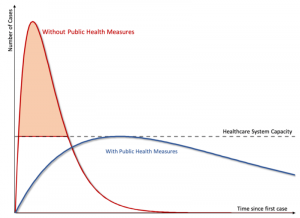

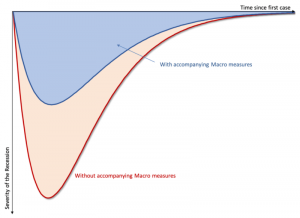

Back on March 19th, 2020, I pointed to this piece by Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas at my blog – Coordination Problem — where he states very clearly the reality constraint in public policy deliberations in the current coronavirus crisis. Without committing one way or another on the debate over the epidemiology models being used, I thought, and still think, this way of putting it could serve as a very useful point of departure for serious conversations about trade-offs, short-run/long-run, and public policy in a liberal society. By now you have seen these graphs numerous times, but they are still useful to draw your attention to the issue at hand.

Public Health in Pandemic

Economic Policy During Pandemic

My sincere hope was that by framing the public discourse in a discussion concerning trade-offs, we would be able to deliberate our way to a rational consensus that will reduce regime uncertainty, and free up the creative powers of our civilization to both address our public health crisis and make sure the economic future is bright. That was perhaps a foolish hope given the reality of politics and the state of our intellectual culture, especially the divisiveness and mood affiliation attractors of social media and much of cable news coverage.

When I wrote Why Perestroika Failed: The Politics and Economics of Socialist Transformation (1993) the public conversation was different inside and outside of the former Soviet Union and East and Central Europe. The problem with the communist economies was a feature of those systems, and thus the policy conversation focused on changing those features as quickly and clearly as possible. I discuss this in chapter 7 of the book.

That created its own set of serious difficulties, and the subsequent history has no doubt revealed the consequences those difficulties presented. But there really is no debate that structural change of the system was required. The situation was also different at the time of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09, which again identified deep structural weaknesses in the system that resulted from misaligned incentives and the distorted signals caused by monetary mischief as Steve Horwitz and I argue in our monograph The House That Uncle Sam Built (2009).

The problems revealed in 2008 were a feature, not a bug, and thus required changing those features as quickly and clearly as possible if the economic vulnerabilities were going to be addressed. Again, doing the sort of structural change required has its own difficulties, and subsequent history again reveals the consequences of failing to overcome those difficulties.

But, in my opinion, this crisis is different not in degree but in kind from those previous shocks. It is literally and figuratively a bug in the system. Our current crisis was not endogenously created, though no doubt significant vulnerabilities of key sectors are being exposed (e.g., my own industry of higher education). Those vulnerabilities will need to be addressed, but it is important to stress that they were not caused by the coronavirus; they were revealed by the policy choices made in attempting to fight that coronavirus.

And, those vulnerabilities are a function of policy choices that were made over the years — in particular since 9/11 and 2008, but more generally dating back decades (consider, e.g., the third-party payer problem in health care). These vulnerabilities must be addressed because they exacerbate the negative consequences of this shock, and many of the policy “mental models” that politicians and intellectuals propose only will augment the negative, rather than ameliorate the problem in health, education, inequality, and economic volatility.

This public debate must take place, and sound economics must once again be stressed if we are to have any hope in sustaining a liberal society of peace and prosperity. However, while never far from our minds, that debate must wait in line as we first have to see ourselves out of this morass.

The current situation is a result of an exogenous shock and the policy responses to that exogenous shock that have in effect shut down significant sectors of the economy. In tackling the trade-offs, we need to think hard about how to meet the challenge and unleash the creative power to simultaneously reduce human suffering and restore economic prosperity and peaceful social cooperation. The administration has released a plan that comes in 3 phases. The primary criteria for moving from Phase 1 to 2 and finally to 3 will be public health indicators.

As Doctor Anthony Fauci put it at the press conference last Thursday.

But we feel confident that sooner or later we will get to the point, hopefully sooner with safety as the most important thing, to a point where we can be–get back to some form of normality.

The one thing I liked about it that Dr. Birx said so well is that, no matter what phase you’re in, there are certain fundamental things that we’ve done that are not like it was in September and October. You want to call it the new normal, you can call it whatever you want. But even if you are in phase 1, 2, 3, it’s not okay, game over. It’s not.

At that same conference, it was made clear that the US with its large land mass and its 330 million population will still pay lip service to federalism, and the authority rests with the state governors to decide when and how to re-open their respective economies. Some of the governors have formed regional agreements with each other.

Those of us who look to Hayek as an inspiration for their research program view economics as a coordination problem, and we see entrepreneurship as the solution to that problem. We study entrepreneurship in the public, private and independent sector to see how a variety of coordination problems are in fact solved or at least ameliorated by creative and clever human actors.

These acts of entrepreneurial alertness and creativity are never trivial acts ex ante but are often acts of bold courage; of voyages into an unknown and uncertain world. But unless these acts are taken, the coordination problem persists and opportunities for gains from trade and gains from innovation are unrealized.

In short, absent the productive specialization and peaceful social cooperation that is realized when coordination problems are solved improvements in the human condition are lost. This is not exclusively a loss of material progress, but a loss of all the things that lead to human betterment that material progress delivers for us.

Within the set of serious coordination problems to be addressed we must include macro volatility problems associated with the manipulation of money and credit, and the corresponding misallocation of capital and labor. In short, a standard boom-and-bust story in the Austrian Theory of the Business Cycle. But not all macro volatility problems are money- induced distortions and corrections.

The Real Business Cycle focused attention on exogenous shocks to the system – be they from non-monetary policy changes or random events. These exogenous shocks can be, and often are, compounded by errors in the policy responses to them. When we were conducting the Katrina project at Mercatus, one of the issues we focused on repeatedly was how to try to avoid “compounding the fury of nature with the folly of mankind.” Unfortunately, that problem is almost as difficult to manage as the consequences of the external shock itself.

But collective action will be required. The great economists Thomas Schelling put his finger on this in an interview in the LA Times back in 2005. As he put it:

“There is no market solution to New Orleans,” said Thomas C. Schelling of the University of Maryland, who won this year’s Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his analysis of the complicated bargaining behavior that underpins everything from simple sales to nuclear confrontations.

“It essentially is a problem of coordinating expectations,” Schelling said of the task that Vignaud and her neighbors must grapple with. “If we all expect each other to come back, we will. If we don’t, we won’t.

“But achieving this coordination in the circumstances of New Orleans,” he said, “seems impossible.”

But Schelling was too pessimistic; private, public and independent sector entrepreneurs figured creative and clever ways to serve as focal points of orientation for individuals to come back and rebuild in New Orleans. The task was daunting, but it was not impossible. They solved the coordination problem through ingenuity, grit and determination, and once their bold and courageous acts were taken, others found hope.

I have written here already about the trade-offs, and about expectations, and the plans to reopen the economic system following public health guidelines. These all must be studied carefully and dispassionately — without over-optimism or over-pessimism. But one thing is clear in my mind; we will need to solve once again a problem similar to what Schelling identified for New Orleans. If we don’t, expectations will guide actors away from moving in the desired direction.

One of the key issues to stress, which I don’t see stressed enough, is that we do not need a cure to get back to a semblance of a functioning economy. All that is needed is credible assurances that effective treatments have been developed, and hospital capacity is not exhausted. Ben Powell recently reminded everyone that the original intent of the policy path chosen was not to eradicate the virus, but to buy time for the hospital system to be able to function properly rather than be overwhelmed by patients.

Our hospitals must have the capability of servicing patients that have become infected, and also conduct their normal operations of caring for those who are acutely ill, who suffer from accidents, develop chronic illnesses, or are victims of violence. In other words, the medical system has to be able to function. Solve these two issues – treatments that ease us through the illness and adequate hospital care if needed — and the coordination problem of getting back to work will go a long way toward being solved. Or, at least solved enough that we can all start to get back to our lives.

Which by the way is not just our jobs, but our relationships and our plans to spend quality time with loved ones, to celebrate the joys of reunion, to find comfort in each other as we struggle with the trials and troubles of living. Our commercial lives are not limited to our professional lives, but are intimately interwoven with our personal and communal lives.

A society of free and responsible individuals who can participate and benefit from the market economy and who live in caring communities with family, friends and neighbors; that is what the liberalism of Tocqueville as well as the libertarianism of Nozick promised. We shouldn’t forget that vision of a free society, and we should not let critics try to use this occasion to slander liberalism and libertarianism with being either ill-equipped or lacking in compassion in moments of public crisis like this. We must demonstrate in theory and in our deeds that true radical liberalism provides the robust answer to these turbulent times.

Again, it is not a cure we must wait for; we just need credible assurance from entrepreneurs in the public, private and independent sector that treatments and medical capacity are such that our own risk preferences and risk management strategies can take over.

There are other serious steps that can be taken. We do not need a selfless and saintly super brain to achieve any of these, just ordinary human actors who are alert to opportunities they are presented with. One of the most important realities is that while it is true that the spreading of a virus represents a classic negative externality, and coordinating a response represents a classic public goods problem, as we have learned repeatedly throughout the judicious study of economic theory and history, the ultimate resource is the human imagination and clever and creative individuals that will test out, discover, and create a variety of solutions to externality and public goods problems, and in so doing often transform them into non-problems.

This results from slight changes of behavior on the relevant margins, or from seismic change due to introduction of novel technologies, products, or services. Today’s inefficiency is tomorrow’s profit for the entrepreneur that is able to internalize the externality, or exclude free riders of the public good in question.

Right at this very moment, not just in government-sponsored labs, there are individuals looking for solutions to our current problem. And, not just experiments with potential vaccines, but new products that will help us reduce our risk. Individuals desperate for a return to their normal life are eagerly figuring out practices that will provide a modicum of relief from the current anxiety. A free people is not a helpless people. We adjust, we adapt, and we take on the responsibility of being architects of our own fate.

The obvious public focal point that many point to would be wide scale testing and antibody determinations. This would be fantastic, but if we could get credible assurances that effective treatment options and medical capacity is there I believe that despite whatever calm analysis of the numbers tells us, folks will begin to believe that they are relatively safe to enter social spaces once again. And, it is this entering back into social spaces that will get us over the coordination problem that Schelling identified in the context of Katrina.

The existing pressure on the medical system has to be reduced by ingenuity and innovation, not I would argue, by improvements in command and control management. This includes alternative supplies of needed equipment and personnel being guided to most urgent areas, by scientists working hard to discover effective treatment options by repurposing drugs or through creative combinatorial thinking. Again, the coordination problems we are facing will be addressed by creative and clever entrepreneurs (who are also erring but always striving to correct) in the private, public and independent sector.

When these entrepreneurial acts produce results that can serve as a focal point to others that it is within the reasonable calculations to return to social space in which we work, play, and live with one another, then additional work will be required to clean up the mess that the folly of mankind has created in the wake of the tragic fury of nature. When we embarked upon our study of Katrina back in 2005, we found hope in a classic statement from the great classical economist J. S. Mill’s Principles of Political Economy:

what has so often excited wonder, the great rapidity with which countries recover from a state of devastation; the disappearance, in a short time, of all traces of the mischiefs done by earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, and the ravages of war. An enemy lays waste a country by fire and sword, and destroys or carries away nearly all the moveable wealth existing in it: all the inhabitants are ruined, and yet in a few years after, everything is much as it was before.

Just in the 20th century economic history of the US, calm resolve may be provided in these difficult times by looking at the economic consequences of 1918-1919; 1952; 1957. Horrendous toll and tragedy befell so many families and yet economies recover, grow and develop due to expansion of the opportunity for gains from trade and gains from innovation. This doesn’t diminish the tragic suffering.

Social systems should be judged both by how well they minimize human suffering, and maximize the opportunities for human flourishing — that is what striving for a “good society” is ultimately all about.

I hope someday soon we will once again be having very rational yet vigorous discussions about the fundamental issues related to the liberal principles of justice and political economy, and we can point to the resiliency and ingenuity of a free people even in the face of adversity as one of the main arguments in favor of true liberal radicalism.

Peter J. Boettke is a University Professor of Economics and Philosophy at George Mason University, as well as the Director of the F. A. Hayek Program for Advanced Study in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, and BB&T Professor for the Study of Capitalism at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Boettke is a former Fulbright Fellow at the University of Economics in Prague, a National Fellow at Stanford University, a Senior Fellow with the American Institute for Economic Research, and a Hayek Visiting Fellow at the London School of Economics. This article was originally featured at the American Institute for Economic Research.