In poor countries, welfare state represents a system where businessmen and statesmen work side by side (to plunder money from the people)

The idea of an economic model able to set an improbable combination of economic liberalism with central planning (a middle way between capitalism and socialism), aimed for the best of both worlds to promote social justice, has been fascinated politicians, scholars, artists, the people (voters) around the world. Surfing this wave, welfare state has spread fast and furiously.

Some even say that Nordic countries are the final evidence that it is possible to deliver a prosperous and egalitarian society through state intervention, mixing free market with high taxes in order to get high living standards and smaller inequality grab.

Well… Latin America tells another history, a narrative where welfare state leads to weak social-economic results and additionally makes feasible a cozy alliance between businessmen and statesmen, which is established to extract huge amounts of money from the people and redirect it to the rich (some entrepreneurs and politicians).

Figures Never Lie

People in Western have repeatedly been told the way of reducing poverty and curbing social inequality is enlarging the government’s role in economy through expansion of public services and works.

In Latin American this train of thought came as a tsunami. From mid-1990s on, welfare state was chosen (by voting… in ballots) to carry the hope for a better future. Brazil, Chile, and Argentina are lived examples of that – their people elected over and over again politicians who promised to bring this agenda to life.

But according to scholars such as Sonia Fleury, earlier than that, since early 1970s, social policies had already started to impose this regime and its variations – there are at least two types: (1) a public universal system of integral social benefits, in which the state guarantees social rights through an equitable system of social policies; and (2) a dual system that locates the poor in the public sector (of health care and pensions, for example), while those who can afford are stimulated to move towards a private market.

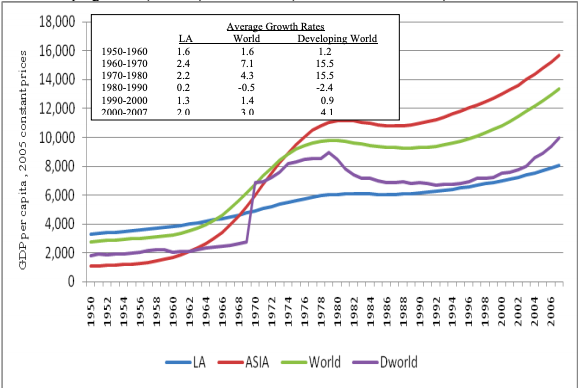

What was the result? We cannot say much good about these countries’ economic growth rates. Latin America GDP per capita rose modestly (not to say it remained stagnated) between 1950 and 2006. Over the same period, comparatively, East Asia and World GDP per capita roared. In other words, particularly (and curiously) after early 1970s, Latin America has lost relative income share on a consistent basis (underperforms consistently) in relation to the rest of the World (on average). Check this out in the chart below:

GDP per capita for Latin America (LA), East Asia (ASIA), the World and the Developing Word (Dworld). Source.

Source: Authors’ own computations on the basis of Penn World Tables 6.3 (2010).

On the other hand, we can say some (bad) things about these countries’ public spending (which skyrocketed). Gross Public Debt of GDP in Brazil rose from 30.6 percent in 1995 to incredible 87.87 percent by 2018. Argentina and Chile followed the same path. In Argentina GPB of GDP boomed from 25.74 percent in 1992 to 86.26 percent by 2018 (it had reached 152.24 percent in 2002). In Chile, it was just 11.08 percent in 2011 and went up to 27.16 percent by 2019.

Nevertheless, until recently, people did not seem so concerned. They assumed everything was being done by the government had an undisputed solidaristic purpose: helping the poor and putting an end to social privileges. Elites were supposedly being overthrown.

But then, came the crises.

In Brazil, the relatively stability reached until early 2000s was shaken especially after 2015. GDP growth shrieked to -3.8 percent, worse result since 1990; real (the national currency) suffered a huge devaluation – the exchange rate real-dollar passed from 1.829 in 2000 to 3.327 (nowadays it is 4.2), inflation (that was 1.65 percent in 1998) reached 10.67 percent.

In Argentina it was not different: GDP growth (stirring 6 percent in 2011) suffered ups and downs and eventually squawked to nerve-racking -2.51 percent by 2018. And how about Chile? Guess what? The same thing! GDP growth went from cheering 6.11 percent in 2011 to shy 1.25 percent by 2017. All over the continent, the combination of slow economic growth and high unemployment along with inflation led to stagflation (what we checked in the chart above).

But what is more remarkable is that while these countries were slumming into crises, a small group of entrepreneurs enjoyed profits that grew exponentially. For instance, between 2003 and 2015, Odebrecht (the largest Brazilian’s construction firm) saw its revenue burst from $4.25 billion to enviable $44 billion. How is that possible? It might sound weird, but the answer was provided by the criminal justice system.

A Fruitful (And Shameful) Alliance

In early 2015, a continental wide anti-bribery operation cranked by the Brazilian Federal Police (Car Wash Operation) discovered that a shocking scheme of illegal payments, over-invoiced contracts, and bribes had been operated for more than a decade throughout Latin America. The public contracts under investigations total a striking $4.2 trillion – money that had fleeced out from taxpayers supposedly to afford public works and services (in the name of commonweal, of course).

And although Brazil was the initial epicenter, the multiple and interconnected trails of corruption were traced far beyond its borders as foreign politicians and companies were dragged in: (a) in Argentina, three public works and $35 million in illicit payments made during Cristina Kirchner government were put under investigation; (b) in Chile, an informant said that the campaign of the president Michelle Bachelet was sponsored with slush funds; (c) in Peru, the former president Alejandro Toledo was arrested due to having taken $20 million in exchange for facilitating contracts related to the building of an interoceanic road linking Brazil and Peru.

By the way, as some of the suspects taken into custody agreed to co-operate with investigations, the whole organization fell into pieces, exposing that the corrupt entrepreneurs had agreed to channel a share (up to five percent) of every over-invoiced contract to politicians, not just to make them rich beyond their wildest dreams but also to fund election campaigns and keep the governing coalition in power (the so-welcomed welfare state) – in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Venezuela, Equator…

Isn’t it scary?

After these revelations, it became pretty clear (I suppose) that Latin American people had been deceived. They have been paying taxes to afford a colossal scheme of corruption which used the need for public services to extract money from most people and redirect it to a small group of corrupt important politicians and the biggest corporate executives.

Capitalism Of Coalition

Nowadays, when someone claims that welfare state means combining market with public utility services, I cannot help thinking the reality shows it forges a capitalism of coalition where statesmen and businessmen agree on how to extract money from the people in the name of helping the needy.

Thinking about this juncture, never has it been more obvious the reason why, in some countries (such as USA) multi-millionaires make their fortune mainly in technological field, whilst in other places (especially developing countries) the “capitalism of coalition” provides the best opportunities for big companies specialized in biddings – most of the super-rich in Latin America (so-called “entrepreneurs”) made and grew their fortune not exactly in the marketplace, but building public works and providing services required by welfare state.

As Lew Rockwell warns, welfare state expenses have been growing since 1980 in the name of helping the poor. But the money largely does not go to the poor, who receive just the crumbs, but to those interest groups powerful enough to bribe and lobby in favor of redistribution. The real money goes to the “pooerers” (the real defenders of the poverty), consultants, big companies that build state-subsidized housing (VPOs), public officials, and, specially, the members of bureaucracy who operate the whole scheme. The poor are maliciously and intentionally turned into a perpetual subclass, government dependent, in order to allow that some parasites can live comfortably well at the expense of all the rest of society.

You Can’t Be Too Careful

Now, it seems hardly surprising that some guys get richer and richer in countries like Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Peru, Colombia… even though, at the same time, the rest of the citizens struggle into consecutive crises and kept being poor. The key-factor seems to be the covenant between corporations (powerful enough to make alliance with the State) and the welfare state project (whose framework is based on public expending).

I know most part of welfare state supporters is well intentioned. However, the road to (social and economic) failure is full of good intentions and as Adam Smith beautifully recall, “there is no art which one government sooner learns of another than that of draining money from the pockets of the people”. You cannot be too careful when the matter is the State’s power.

Jean Vilbert holds a Bachelors and a Masters of Law. He is currently a Criminal Judge and Professor in Brazil. You can reach him at jeanvilbert@gmail.com.