At the dawn of the nineteenth century, the Kingdom of Prussia was soundly defeated in multiple territorial battles with Napoleon’s French Empire. Under Napoleon, France’s revolutionary army had integrated new logistical methods into their military strategies. In particular, the French had employed Levée en masse, which was a policy of mass conscription that bolstered national unity. Prussia’s army under the reckless Frederick William II, meanwhile, had lost their once-renowned militaristic discipline. Nothing speaks like results, and in 1806, in three battles over what is now German land, the disorganized Prussian soldiers surrendered to the well-oiled and unified machinery that was the Napoleonic army. Napoleon seized more territory, and Prussia was left with an army of merely 42,000 men.

Prussia’s political class lost the confidence it had earned in previous decades, and the stark contrast between the quality of the French and Prussian armies was not lost on them. Seeking a method by which to both infuse their forces with discipline and instill unquestioning nationalism in its citizenry, Prussian statesmen turned to philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt, whom they appointed as Minister of Education in 1809.

Humboldt’s intentions were noble. He advocated a public system of education in which all citizens, irrespective of class or social status, were taught precisely what would be required to live a productive life. As he wrote to the Prussian king, “There are undeniably certain kinds of knowledge that must be of a general nature, and…a certain cultivation of the mind and character that nobody can afford to be without.”

But intentions do not equal results. Humboldt’s ideal of spreading the right knowledge to the right people translated, in practice, to the standardization of every aspect of public education. Instruction, examination, curricula, and textbooks were all treated as machinery to be employed in the “education” of the masses. Furthermore, the fact that the Prussian government was sponsoring Humboldt’s passion project ensured that the philosopher’s dreams were channeled in ways that served said government’s interests, which, as noted above, were to create an obedient and loyal citizenry.

As educator John Taylor Gatto notes in his book, The Underground History of American Education, the Prussian educational system took children away from their families and local communities and aimed to convert the youth into:

“1. Obedient workers for the mines.

2. Obedient soldiers for the army.

3. Well-subordinated civil servants to government.

4. Well-subordinated clerks to industry.

5. Citizens who thought alike about major issues.”

They called it schule.

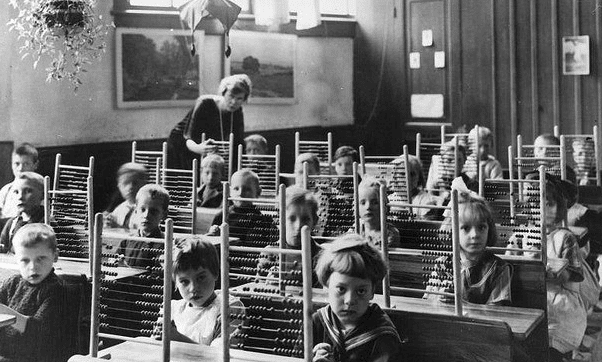

By the 1840s, Prussia’s school system was operating as smoothly as the factories it so creepily mirrored. Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, the secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education, Horace Mann, sought a method by which to impose order onto “unruly” children. Naturally, he was impressed by the Prussian model’s ability to collectivize, mollify, and subordinate the minds of its citizens. Mann succeeded in implementing it in Massachusetts and, like so many government programs, it proceeded to spread so far beyond its original scope until no one could imagine what life had been like without it.

In America, our youngest minds, the most malleable amongst us, are sent daily to undecorated buildings against their will. Once there, they will literally pledge allegiance to the flag of the most powerful government that the world has ever seen. History is taught as a history of governments, of “good guys” and “bad guys.” Even science and mathematics classes emphasize the facts of each domain, rather than their beautiful underlying explanations, and the problems that such explanatory theories have solved in our worldview. For example, students will be forced to memorize the names and spatial order of the planets, but not the explanation as to why our naming scheme is arbitrary in the first place.

The mind-molding continues. Students will be trained, doglike, that “good boys and girls” sit in their chairs when told to do so. Creative, individualistic behavior will be judged to be “disruptive,” and drugs are often encouraged onto those wildlings in order to subdue them. High grades are rewarded to those who follow instructions most accurately, who regurgitate facts and figures. That a student is bored is regarded as a problem originating with the child, rather than with the product being presented to him. To question a teacher’s authority, or the relevance of the course material, is considered rude.

The list goes on. But perhaps the most insidious effect of mandatory schooling is that it deludes people into thinking that they are cognitively impotent. That is, people are subtly trained into thinking that school is the only way to learn something. Consider the common refrain, “I’d love to learn physics, but I was never very good at it in school,” or, “I want to learn how to code, but my school didn’t offer any classes on it.”

Another manifestation of this learned impotence is the disproportionate reverence we hold for those with degrees in higher learning. This is a magic trick that has elevated the professorial class to the status of priests of previous ages. No matter how many authoritative certificates one earns in the academy, truth is obtained the same way as always—by conjecturing ideas, criticizing them, and retaining those that survive. Nowhere in this scheme is a degree to be found.

As David Deutsch explains in his 2011 book, The Beginning of Infinity, all people are “universal explainers.” That is, a person who is capable of understanding some arbitrary concept is necessarily capable of understanding any idea that can possibly be understood. Acquiring knowledge can come from sitting in a classroom, or from a lecture by a professor, but this is far from a law of nature—quite the opposite. One may learn an idea in a literal infinite number of ways. That a person lacks a degree is no impediment to learning any subject at all.

In short, we do not need them.

Just as the printing press allowed the masses to circumvent religious leaders and read the sacred texts on their own, the Internet is performing a similar function before our very eyes. To whatever extent the academic class had been the gatekeepers of knowledge, digital decentralization has rendered them superfluous as teachers. No one needs a high school degree to begin learning cellular biology. Whereas in yesteryear, one may have genuinely needed to take a college course to learn the material, now such knowledge is available across an almost literally uncountable number of platforms. The curious person may watch a YouTube series, read articles on Wikipedia, Tweet at a famous biologist, etc. The notion that one must learn inside of the dry walls of an academic setting is like demanding landline technology in an age of iPhones.

This article is not intended to denigrate any particular teacher or PhD program. On the contrary, these arguments should engender excitement and optimism. The idea that nothing stands in the way between you and anything you wish to understand is an extremely liberating message. The Internet has allowed for a myriad of educational flowers to bloom, many of them free for the picking. There is no perceived authority in the path to whatever knowledge piques your interest. With the press of a few buttons, you can stand on the shoulders of giants and “see” any knowledge that civilization has yet forged. We’re all intelligentsia now.