This paper was originally published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the International Studies Association and is reprinted with permission of author.

Through the use of survey methods, the study presents the first systematic comparison of America-based international relations professors to think tank employees (TTEs) in terms of their preferred conduct of the United States in international affairs. The difference between the two groups in their support for military intervention is stark. TTEs are 0.47 standard deviations more hawkish than professors based on a standard measure of militant internationalism (MI). Controlling for self-described ideology mitigates this effect although it remains statistically significant. Beyond quantifying their relative foreign policy preferences, this study helps to resolve why TTEs tend to assume more hawkish policies. The authors find evidence that hawkishness is associated with proximity to power. Professors who have worked for the federal government score higher on MI, as do TTEs based at institutions located closer to Capitol Hill. In general, the results point to a self-selection mechanism whereby those who favor interventionist policies are more likely to pursue positions to increase their policy influence, perhaps because they know that powerful institutions are more likely to hire hawks. Alternative explanations for differences, such as levels or kinds of foreign policy expertise, have weaker empirical support.

Introduction

In September 2002, a prominent group of international relations (IR) professors penned an open letter in the New York Times against the invasion of Iraq. Although the thirty-three scholars spanned the political spectrum, they were united in their opposition to a US-led war against Saddam Hussein. These scholars spoke for much of the field, as the majority of IR professors also opposed the war (Friedman and Logan 2016, 23). An even stronger consensus coalesced in Washington, DC-based think tanks, but in favor of military intervention as reflected in op-eds, television appearances, policy papers, and direct appeals to Congress urging US-led regime change in Baghdad (see Rosentiel 2008; Long et al. 2015).

The debate leading up to the 2003 Iraq war lends anecdotal support for two widespread albeit untested assumptions about the relationship between IR professors and think tank employees (TTEs), namely “fellows.” The first is that the former wield less influence than the latter in affecting policy (Feulner 1985; Higgott and Stone 1994; Haass 2002; Keskingören and Halpern 2005; Misztal 2012; Stone 2013; Rothman 2014; McGann 2016; Maliniak, Peterson, and Tierney 2019). Nicholas Kristof (2014) captured this sentiment in a New York Times column entitled “Professors, We Need You.” In an indictment of the academy, he denounced IR professors for their supposed irrelevance: “Most of them just don’t matter in today’s great debates. The most stinging dismissal of a point is to say: ‘That’s academic.’ In other words, to be a scholar, is, often, to be irrelevant.” Kristof overstates the “cult of irrelevance” in the academy (e.g., Goldgeier and Jentleson 2015; Jentleson 2015; Coggins 2019), but surveys of policy-makers reveal that they tend to ignore scholarship and rely instead on op-eds, policy papers, and other forms of informational advocacy that are generally the province of TTEs (Avey and Desch 2014; Gallucci 2014; Desch 2019). Whereas policy-makers often trivialize the impact of academics, think tanks are routinely touted as indispensable. As President Lyndon Johnson said of the Brookings Institute, “You are a national institution, so important. . .that if you did not exist we would have to ask someone to create you.” House Speaker Newt Gingrich likewise thanked the Heritage Foundation for its “tremendous impact not just in Washington, but literally across the planet” (Rich 2004, 1). While think tanks boast of their impact (Shapiro 1984), most professors acknowledge that their scholarship appears to exert a “frustrating lack of influence” despite a widespread desire to affect policy (Nye 2009). Think tanks are incentivized to exaggerate their own influence, but even insider accounts from their critics underscore the difficulty recent administrations have faced in pursuing independent foreign policies (Woodward 2011; Rhodes 2019; Draper 2021). Such observations accord with the conventional wisdom even if none of them definitively demonstrates that academics are less “policy relevant” than TTEs, as establishing relative influence is notoriously difficult methodologically (McNutt and Marchildon 2009; Stone 2013; Horowitz 2015).

The second assumption reinforced by the Iraq war is that TTEs disproportionately favor military force and are thus more “hawkish” than IR professors. This perspective solidified in the mid-1970s with the founding of the Heritage Foundation (Rich 2001). Journalists have periodically opined that think tanks are responsible for pushing hardline US policies from the Middle East to East Asia (e.g., Hodge 2010; Lipton, Williams, and Confessore 2014; Beauchamp 2017; see also Abrahms and Glaser 2018). This perception of think tank policy preferences is based on a few salient cases rather than systematic testing. As Rich (2004, 8) points out, this “lacuna” in the literature is striking given the prevailing view that TTEs are successful in translating their foreign policy preferences into action. The dearth of research in this area is also problematic as prominent scholars contest the conventional wisdom. Most notably, Walt (2018, 122) speculates that academics and TTEs tend to share essentially indistinguishable foreign policy preferences as neither “question[s] the strategy of liberal hegemony.” Although prior research has elucidated the policy preferences of academics and policy-makers (e.g., Wemheuer-Vogelaar et al. 2016; Green and Hale 2017; Zarakol 2017), no study has systematically compared the foreign policy beliefs of TTEs to IR professors.

Our study is the first to make this empirical assessment via survey methods. Given the important role that think tanks ostensibly play in US foreign policymaking, it is surprising that no other quantitative scholarship has been published on what TTEs actually believe compared to their academic counterparts. The differences in their foreign policy preferences are vast; TTEs score almost half a standard deviation higher in “militant internationalism” (MI) than professors, with substantially more hawkish views on critical foreign policy areas pertaining to China, North Korea, and Iran, as well as whether the United States was “right” to intervene militarily in Iraq and Libya. This finding remains robust even after controlling for self-described ideology.

Our study is not only the first to quantify the foreign policy preferences of TTEs compared to academics, but also the first to propose and test a data-backed explanation to account for their differences. Evidence abounds that hawks gravitate to positions of power because they attach greater value than doves to influencing policy. This parsimonious explanation can account for variation in hawkishness both between and within respondent groups. Not only are hawks more likely to work in think tanks over universities, but professors who have worked for the federal government score higher on MI, as do TTEs based at institutions located closer to Capitol Hill. Proximity to power—whether measured by profession, government employment experience, or physical distance—consistently predicts greater support for the use of military force. These results point to a self-selection mechanism whereby those who favor relatively interventionist policies abroad are more likely to pursue positions to increase their policy influence. In short, we find that hawks flock to positions of power.

This paper proceeds in five main sections. We begin with a brief summary of the extant scholarship on think tanks, highlighting their role as an important albeit understudied link between academe and policy. Then, we explain our survey instrument for assessing the foreign policy preferences of TTEs relative to IR professors and present the results. Next, we propose and test a parsimonious explanation to account for why hawks are overrepresented in think tanks compared to universities. Overall, the data lend support for a self-selection process in which hawks flock to positions of power in order to maximize their policy impact. We also consider alternative explanations, particularly the possibility of a reverse selection process in which institutions closer to power select hawks over doves for their perceived expertise. There is relatively weak empirical support for this mechanism, as multiple measures of foreign policy expertise fail to predict either hawkishness in opinion makers or their tendency to fill positions with greater policy impact. The paper concludes with the research and policy implications.

Think Tanks: The Missing Link between Academe and Policy

A substantial body of political science addresses the foreign policy preferences of “elites,” but tends to focus on policy-makers and academics rather than TTEs as the unit of analysis (e.g., Rich 2004; Wemheuer-Vogelaar et al. 2016; Green and Hale 2017; Zarakol 2017; see also Zaller 1992). The most common observation about think tanks in the literature is the relative absence of empirical research on them.1This is changing (e.g., Weaver and McGann 2017; McGann 2019). As Abelson (1996, ix) noted in the 1990s, “[t]he study of think-tanks and their role in American politics has largely been ignored.” Stone (2013, 1) elaborated that “most public policy texts fail to discuss think tanks as either a source of policy innovation or as a group of organizations that seek to inform policy.” Yet, the weakness of scholarship on think tanks has not dissuaded academics from theorizing about the source of their presumed influence (Weidenbaum 2010).

From their early twentieth century origins in the Progressive era, think tank giants such as Brookings, the Carnegie Foundation, and the Hoover Institution have been created with the expressed intent to shape government behavior. As a foreign policy director at the Brookings Institution put it, “[o]ur business is to influence policy” (quoted in Lipton, Williams, and Confessore 2014). McNutt and Marchildon (2009, 220) point out that “all think tanks” share this primary purpose. In fact, some definitions of think tanks include this goal. For example, defines a think tank as “an independent organization engaged in multi-disciplinary research intended to influence public policy.” To this end, TTEs work full-time staffing the foreign policy bureaucracy, lobbying politicians and their staff to adopt preferred policies, and shaping public opinion with op-eds, reports, television, radio, and other media appearances in order to create agenda-setting, priming, and framing effects (Iyengar and Simon 1993; Baum and Potter 2008).

Although an important subset of IR professors also partakes in such activities (e.g., Fazal 2014; Byman and Kroenig 2016; Coggins 2019), the traditional mission of universities has been to acquire and impart knowledge “for its own sake” (McGann 2016, 7). Whereas TTEs are mainly rewarded for impact, Nye (2009) remarks that “in many departments a focus on policy can hurt one’s career.” At some universities, junior scholars are advised to wait until they have tenure before engaging with the policy community or media or otherwise cultivating audiences outside the academy (Jentleson and Ratner 2011; Brands 2017). Unlike think tank products, academic research is generally oriented to other academics (Rothman 2014) and evaluated by its scientific rigor, which can result in scholarship that is “abstract, arcane, and sometimes unfit for practical use” (Gallucci 2014). Although policy relevance can admittedly be judged in numerous ways (Horowitz 2015), a quantitative assessment of political science studies in leading peer-review journals and academic presses estimates that fewer than one in five include explicit policy prescriptions (Maliniak, Peterson, and Tierney 2019; see also Nye 2009).

Conceptually, think tanks are typically situated between the oft-detached worlds of the academy and policy. Smith (1993, 13) notes that think tanks function “between academic social science and higher education, on one hand, and government and partisan politics, on the other hand. . .” Abelson (2018, 11) describes think tanks as “research brokers” that act as a “conduit between the scholarly community and policymakers.” Reiterates that think tanks serve as an “important link” in the “long haul from academic theories to actual public policies.” As one of America’s premiere think tanks states: “In its conferences, publications and other activities, Brookings serves as a bridge between scholarship and policy making” (quoted in Medvetz 2010, 552). The United Nations (2003) conceptualizes think tanks in similar terms, as “the bridge between knowledge and power.” Despite this apparent consensus on the role that think tanks theoretically play for academics, no empirical study has attempted to systematically compare their foreign policy beliefs. This “strange omission” (Higgott and Stone 1994, 15) is filled below.

Methods and Results

Through the firm Qualtrics, we surveyed samples of both IR professors and TTEs to assess their foreign policy preferences. For our sample of scholars, we contacted assistant professors, associate professors, and full professors listed as IR specialists on the faculty of the political science departments in R1 and R2 universities. Whereas the status of universities is generally uncontested, the question of what constitutes a think tank can be more elusive (Smith 1993, xiv; Medvetz 2008, 9; Stone 2013, 9; McGann 2016, 9; Abelson 2018, 8). To alleviate this potential definitional concern, our TTE sample is restricted to those employed at what have been referred to as “quintessential,” “premier,” “prominent,” and “elite” think tanks whose institutional status is uncontested (Abelson 2018, 8, 17, 50). Specifically, our sample of TTEs consists of every think tank fellow and policy analyst who specializes in international affairs at twenty of the most influential foreign affairs–oriented think tanks in the United States according to previous rankings (e.g., Dhiraj 2017; McGann 2019). The following think tanks are represented in the sample: American Enterprise Institute, Atlantic Council, Brookings Institute, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Cato Institute, Center for a New American Security (CNAS), Center for Strategic and International Studies, Council on Foreign Relations, Foundation for Defense of Democracies, Freedom House, Heritage Foundation, Hoover Institution, Hudson Institute, Human Rights Watch, Institute for the Study of War, New America Foundation, RAND Corporation, Stimson Center, Washington Institute for Near East Policy (WINEP), and the Woodrow Wilson International Center.2This list is not intended to be exhaustive. In total, our firm e-mailed the survey to 868 professors and 823 TTEs between October 2018 and January 2019. Per convention, financial compensation was provided to boost response rates. Professors and TTEs were offered up to $10 and $30, respectively, for their participation.

Pioneering works by Holsti and Rosenau (1988, 1990) showed that opinion leaders can be categorized by their adherence to different foreign policy orientations. Respondents were supplied questions from Kertzer et al. (2014) based on that scholarship to assess support for MI, cooperative internationalism (CI), and isolationism. Militant internationalists see a conflictual world in which the United States should be prepared to use military force in order to defend itself and protect its interests. Proponents of CI emphasize the benefits of cooperation, participation in international institutions, and engagement toward solving problems afflicting the developing world, particularly human rights, poverty, and the environment. Isolationists favor withdrawing from the world and focusing on domestic problems.3Although sometimes portrayed as competing, these world views are not logically inconsistent with one another, as one could theoretically support the unilateral use of force abroad, global cooperation for other international issues, and a concomitant shift in interest toward domestic affairs (Maggiotto and Wittkopf 1981). In practice, MI and CI are often found together in the form of “liberal hawks,” who favor what has been called “establishment internationalism” (Busby and Monten 2008). Beyond their foreign policy beliefs, the survey also asked respondents questions about their political ideology, current and past employment status, and other demographic information. The online appendix displays the exact wording and ordering of every question in the survey.

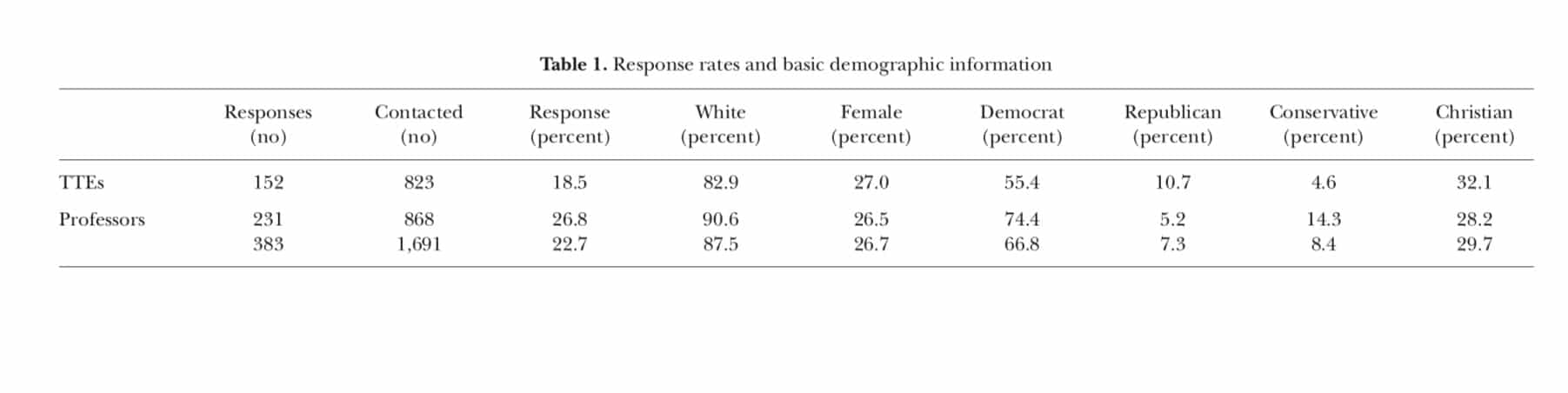

Table 1 displays the response rates, which are within the normal range for e-mail surveys (Sheehan 2001).4For each category, it includes individuals who indicated that they fell into both categories. Both IR professor and TTE samples are predominantly comprised of respondents who identify as white, male, and Democrat (Acharya 2016). While each respondent group leans toward the political left, the ratio of Democrats to Republicans is clearly higher among professors in numbers that are broadly consistent with prior studies on the political leanings of academics (Langbert, Quain, and Klein 2016; Langbert 2018). Other measures of ideology produce similar disparities, for example, 9.2 percent of TTEs who were not also professors approved of President Donald Trump and 13.8 percent described themselves as conservative on a five-point scale, while the equivalent numbers were 4.6 percent and 5.4 percent for professors who did not have an affiliation with a think tank. The extent to which political ideology and affiliation account for differences in foreign policy preferences is addressed throughout this paper.

Relative to professors, TTEs score higher on MI by 0.47 standard deviations (p < 0.001). This relationship is not driven by differences in ideology alone. The inclusion of ideology on a five-point scale as a control variable only reduces the gap to 0.27 standard deviations (p < 0.05), and similar results are obtained when controlling for approval of President Trump on a five-point scale. In the aggregate, TTEs are thus significantly and substantively more hawkish than IR professors even after taking into account self-described ideology. After controlling for ideology, TTEs score 0.35 standard deviations higher (p < 0.01). Although academics have long been tarred as isolationist (e.g., Schlafman 1967), there is no statistically detectable difference in our survey between the respondent groups on isolationism regardless of whether one controls for ideology. The main takeaway is that TTEs favor more active engagement with the world, particularly with regard to the use of force abroad. And their relative hawkishness persists independent of self-described ideology.

In addition to assessing their adherence to MI, CI, and isolationism, the survey queried respondents on specific foreign policy questions. Because hawkishness is a relative concept, our analysis focuses on comparing differences in hawkishness between TTEs and IR professors. TTEs are far more interventionist than professors for every region in the world. This preference manifests itself toward the Middle East in multiple policy positions, including support for both past wars and interventionist actions today. Among TTEs, for example, 13.8 percent of respondents still approve of the decision to invade Iraq in 2003 and 42.5 percent to bomb Libya in 2011 compared to only 5.3 percent and 25.2 percent of professors holding these respective views (support defined as answering between 5 and 7 on a 7-point scale, with 4 marked as “neither support nor oppose”). Only 35.5 percent of professors supported funding Syrian rebels to battle the government of Bashar Assad compared to 50.6 percent of TTEs. The largest difference was over possible support for war against Iran; 13.7 percent of professors answered in the affirmative compared to 35.6 percent of TTEs. On this question, too, controlling for ideology does not eliminate the effect; among self-described liberals, TTEs were almost twice as likely as IR professors to support war with Iran, 17.4 percent versus 9.4 percent. In Asia as well, TTEs are substantially more hawkish than professors. For example, 86.2 percent of TTEs favor deploying ships through the South China Sea in response to Chinese actions there and 13.7 percent support potential military strikes against North Korea for refusing to give up its nuclear weapons compared to 66.1 and 4.6 percent of professors in our survey who held these respective positions. The data do not sustain the view that TTEs as a group are rushing to war. Indeed, some observers may question the hawkishness of TTEs based on the absolute values. However, the results leave no doubt that they are substantially more hawkish on a relative basis, as TTEs are more likely than professors to support MI in the abstract and to favor a more aggressive posture abroad across a range of specific foreign policy issues.5An exception is on their views toward NATO, where over 90 percent of both groups wanted to maintain or expand US involvement

Hawkishness and Proximity to Power

Those results reveal the disparity in policy preferences, but do not explain it. A satisfying explanation would help to account for differences in hawkishness not only between TTEs and professors but also within these groups. In this section, we supply evidence from the survey that hawks are more inclined to pursue positions of power because they are more likely to prioritize influencing policy. Positions of power in this study refer to jobs with superior opportunities or what are known in the literature as “access points” for opinion-makers to impress their views on policymakers and thereby translate foreign policy preferences into action (Binderkrantz, Pedersen, and Beyers 2017).6See Levinson (2021) for recent work on the importance of access in foreign policy decision-making.

This parsimonious explanation accords with our initial observation that TTEs are more hawkish, as they typically have greater exposure than professors to key decision-makers in the policy process (Rich 2004, 12). As prior research has detailed (Abelson 2000), TTEs exploit multiple access points from meeting with Congressmembers directly to testifying before congressional committees to inviting representatives, senators, staff, and journalists to participate in seminars and workshops. These access points facilitate the translation of policy preferences into action because, as one TTE put it, “[i]nfluencing policy is all about relationships” (Arshed 2017, 80).

Our survey indicates that TTEs generally care more than professors about influencing policy. We asked respondents whether in the past year they had engaged in activities to influence policy, such as advocating a policy position on television or in an op-ed. Compared to professors, TTEs engaged in twice as many of these activities (p < 0.01). We also asked respondents, “How important is it for you for your ideas to influence policy in the real world?” Respondents rated the value that they attach to influencing policy on a scale from 1 (“not important at all”) to 5 (“extremely important”). The average scores for professors and TTEs were 2.8 and 4.0, respectively, a difference of over one standard deviation (p < 0.001). Consistent with our self-selection explanation, professors with think tank affiliations score in between these two camps.

For both TTEs and professors, those who attach the most value to policy influence—that is, rate themselves as a 4 or 5 on desired influence rather than 3 or below—score 0.21 standard deviations higher on MI (p = 0.071). We examine not only whether hawks disproportionately work at think tanks and claim to value policy influence, but also whether comparatively hawkish TTEs gravitate to power geographically. Abelson (2018, 92) notes that “being located in Washington clearly provides think tanks with an advantage over institutes not based there in establishing contacts. . .” Indeed, numerous think tanks included in our sample acknowledge that they set up an office in DC to maximize their access points and thus policy leverage (see Gray 1971, 119; Stone 2013, 161). If our selection mechanism is correct, we would therefore expect to find that more hawkish think tanks are headquartered closer to officials in Washington, DC.

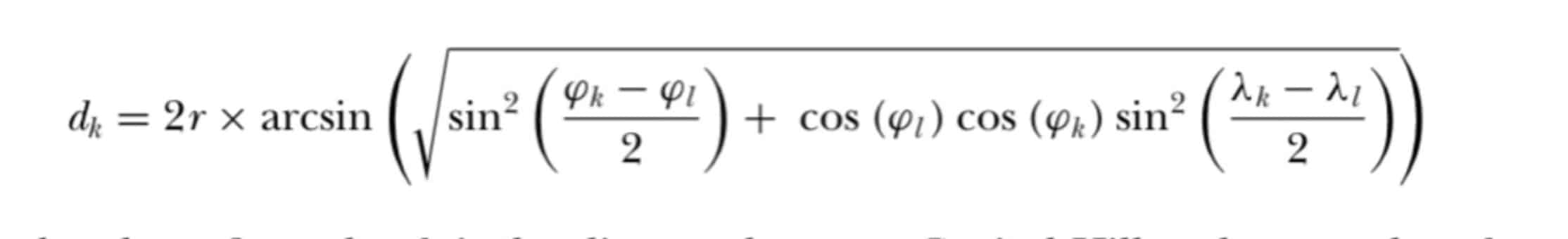

To make this assessment, we use Capitol Hill to represent the center of power and measure logged distance in miles from that location as our proxy for spatial distance. To test the relationship between spatial proximity and MI, we use geocoded data based on the location of respondents when filling out the survey as well as their employer and then apply the Haversine formula to calculate the distance to Capitol Hill (Picard 2019).

In the above formula, dk is the distance between Capitol Hill and respondent k or employer, r is the radius of the earth, and ϕ and λ are the latitudes and longitudes of the two points being compared, with l representing the coordinates of Capitol Hill. We exclude respondents for whom d > 750 as the effect of distance should taper off when they are located too far outside of DC to easily access decision-makers. As our mechanism would anticipate, we observe a negative relationship between logged distance to Capitol Hill and MI among TTEs (p < 0.05), while no such relationship exists among professors. This finding makes sense, as one would not expect to find an association between geographic distance and MI among professors whose job description does not typically prioritize cultivating relations outside of the academy to impact policy (see Jentleson and Ratner 2011; Brands 2017).

We took the averaged standardized MI score of each think tank in the Washington, DC, area for which at least three respondents answered the survey and geocoded not only the respondents, but also their employers to investigate whether think tanks located closer to the center of power tend to be more hawkish. This methodological decision reduces not only the sample size, but also randomness in the coding as respondents were not always located near their employer when they filled out the survey. Averaging the scores for each think tank, we find that institutions are 0.48 standard deviations lower in MI for every mile further away from Capitol Hill (p = 0.19).7The results are stronger when Cato is dropped as an outlier (p < 0.11). Cato is often described as an outlier for its opposition to US military force. See, for example, Friedman (2016). Together, these results indicate how proximity to the center of power in Washington, DC, is associated with more hawkish foreign policy preferences within the think tank community. Hawks disproportionately pursue jobs in think tanks and work in ones with greater access to the locus of decision-making or at least ones based closer to Capitol Hill. Although skeptics may question whether a desire for policy influence can be measured in terms of proximity to Capitol Hill, the data reveal that think tanks based closer to it are indeed significantly more likely to partake in activities to influence policy by advocating positions in the media (p < 0.001).

If hawks gravitate to power, we would also expect them to disproportionately pursue positions in government to directly affect policy and develop relationships for when they return to their home institution. Referred to as the “revolving door” (Feulner 1985, 24; Higgott and Stone 1994, 33; Haass 2002, 7; McGann 2016, 114), the permeability of think tank and government jobs is well established. Nearly 200 employees of the top conservative think tanks served as government officials or consultants in the Reagan administration (Abelson 1996, 15). National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, Secretary of State John Kerry, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, President Gerald Ford, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger, and many other high-level officials have also made use of the revolving door (e.g., Stone 2013, 207). For professors, working in government is even more important for impacting policy because universities do not furnish commensurate access to policy-makers (Council on Foreign Relations 2019). If our self-selection mechanism is supported, we would therefore anticipate that TTEs are more likely than professors to spend time working in government and that those who do are significantly more likely to favor hawkish foreign policies.

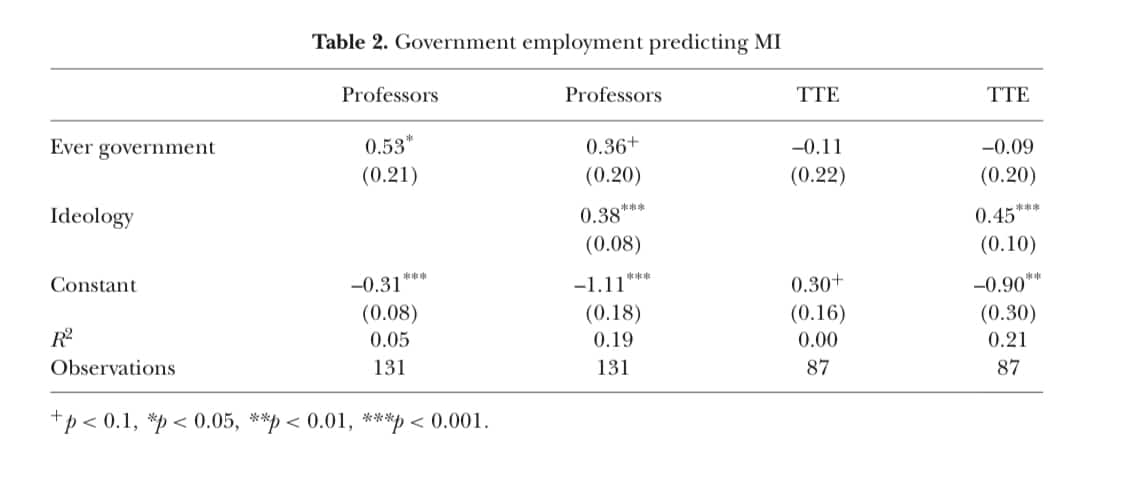

The data reveal that TTEs are indeed over three times more likely than IR professors to have served in government (p < 0.001). In order to test whether government employment is correlated with a more hawkish view, table 2 presents the results of four regressions, with MI as the dependent variable and government service and ideology as the independent variables for each group of respondents.

In accordance with our causal explanation, professors who have been employed by the federal government are more than half a standard deviation higher on MI than academic colleagues who have never worked in government (p < 0.05) and controlling for ideology only slightly attenuates the results (p < 0.10). The proverbial ivory tower is evidently relatively dovish, but the minority of hawks in it are significantly more likely to seek employment in government to partake in policy decisions and develop relationships to facilitate future influence. Relatively hawkish TTEs in our sample are no more likely than their think tank counterparts to have worked in government as the TTE population in the aggregate is quite hawkish, thus restricting the range of the dependent variable (Sackett and Yang 2000). And unlike scholars, TTEs generally have superior policy access by dint of their profession regardless of whether or not they personally serve in government (Smith 1989, 1993).8The sample is admittedly modest as only seventy-one respondents reported ever working for the federal government. Particularly when located closer to Capitol Hill, think tanks act as hosts for government employees (Smith 1993, 131). TTEs do not have the same need to spend time in government to influence policy because the government comes to them.

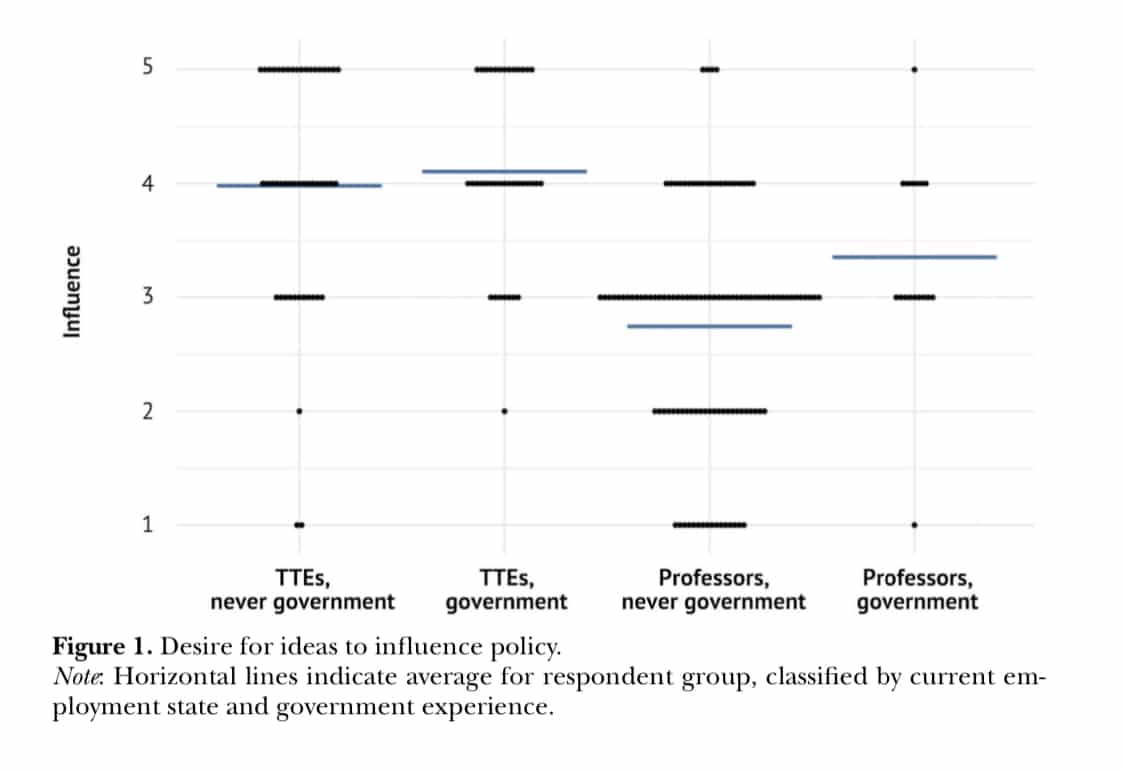

Our self-selection explanation also anticipates that professors who are particularly interested in influencing policy would be more likely to work in the government. Figure 1 displays results from the question on desired influence for four respondent groups depending on their profession and experience working in government. Unsurprisingly, professors who said that it was more important for their “ideas to influence policy in the real world” were significantly more likely than colleagues to have worked in government (p < 0.05). The same is true of TTEs compared to their counterparts who did not work in government, although the average difference within that respondent group is predictably smaller given their proximity to power.

Together, the data indicate that hawks are more inclined to pursue positions of power to maximize their policy impact. TTEs are not only more hawkish than professors, but say that they care more about influencing policy. Compared to universities, think tanks offer hawks greater access points for translating their policy preferences into action. Even within think tanks, the comparatively hawkish gravitate to ones with superior access to the locus of decision-making or at least ones located closer to Capitol Hill, which engage in more activities to influence policy. Foreign policy professionals intent on translating their preferences into action disproportionately take jobs working in the federal government. TTEs are more likely than professors to exploit this opportunity. And when professors are hawkish, they are more likely than their dovish colleagues to work in government, which affords them a special opportunity to network and affect policy. In these ways, the survey data accord with our selection thesis, helping to account for differences in hawkishness not only between TTEs and professors but also within these important classes of foreign policy opinion-makers.

Alternate Explanations

There are other possible explanations for why TTEs are more hawkish than professors. It is worth investigating whether institutions closer to power select hawks over doves for their apparent expertise. This causal story would reverse agency from the individual to the institution if hawks were favored for their perceived regional knowledge. Indeed, the terms think tank “fellow” and “expert” are often used synonymously (e.g., Smith 1993, 130; Misztal 2012, 129) whereas the policy expertise of IR professors is sometimes called into question (e.g., Gallucci 2014; Brands 2017). The data do not support this interpretation as multiple indicators of expertise fail to reliably predict MI, hawkishness on specific policy issues, or even positions closer to power, with the exception of working at a think tank itself.

Formal education is often seen as an indicator of expertise (Halse and Mowbray 2011). We examined whether respondents who have obtained a doctoral degree are more likely to be militant internationalists or work in positions closer to power. On the contrary, both measures are negatively associated with formal education. Among professors, for example, 98 percent have a PhD compared to only 39 percent of TTEs in our sample (p < 0.001), TTEs with a PhD were not significantly more likely to take a job in government and the coefficient is in the opposite direction, TTEs with PhDs do not score higher on MI than TTEs without them and the coefficient is again in the opposite direction, and TTEs are still more likely than professors to be militant internationalists after controlling for formal education levels (β = 0.31, p < 0.10). If we accept PhD obtainment as a possible indicator of expertise, then the data are inconsistent with the reverse selection narrative in which hawks are selected for their apparent knowledge by institutions closer to power.

Other proxies of expertise also fail to predict hawkishness. The survey asked respondents to rate their foreign language proficiency, another standard measure for assessing regional expertise. Foreign language skills do not predict hawkishness among either professors or TTEs. For example, neither professors nor TTEs who speak Chinese are significantly more likely to favor the hawkish position of sending US warships through the South China Sea. Similarly, Russian-speaking professors and TTEs are no more likely to favor North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) expansion. Confidence in these assessments was hampered by the limited number of observations. The results do not sustain the view, however, that institutions closer to power prefer hawks for their apparent expertise as proxied by formal education levels or foreign language proficiency.

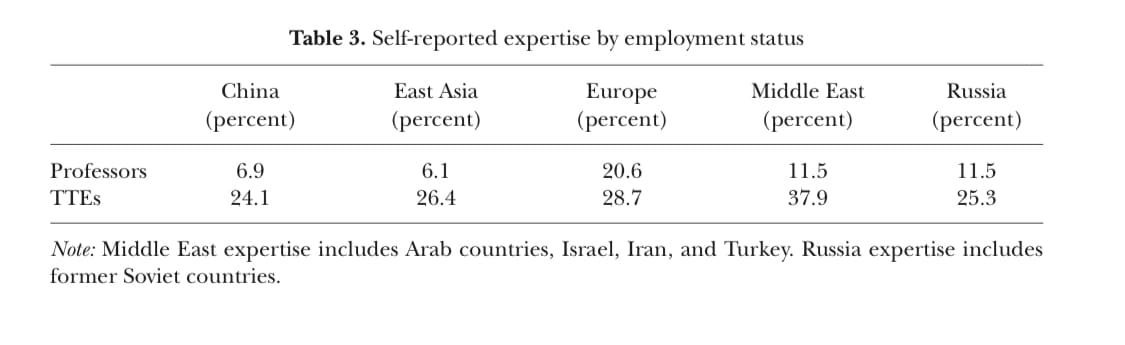

To further investigate a potential relationship between expertise and hawkishness, respondents were asked whether they considered themselves “experts” in various regions of the world. Table 3 shows that TTEs are significantly more likely than professors to rate themselves as experts on Russia (p < 0.01), the Middle East (p < 0.001), China (p < 0.001), and East Asia (p < 0.001). The differences are substantial; for example, only about 7 percent of professors viewed themselves as experts on China compared to 24 percent of TTEs.

Although TTEs are more likely to be militant internationalists and regard themselves as experts, a closer examination of the relationship between hawkishness and expertise finds that they are weakly related. On the subject of China, for example, both professors and TTEs who rate themselves as experts are no more likely to maintain the hawkish view that the United States should send ships to the South China Sea to warn the Chinese against building artificial islands there. Neither professors nor TTEs who claim expertise on Russia are significantly more likely to favor NATO expansion. For both professors and TTEs, self-described East Asia expertise likewise fails to predict respondent support for a military strike against North Korea if it refuses to give up its nuclear weapons. A partial exception is on the Middle East, with self-described regional experts being more likely to support war with Iran (p < 0.001). Among professors only, those who rated themselves as experts in the region were more likely to agree with the statement that military interventions against Iraq in 2003 (p < 0.001) and Libya in 2011 (p < 0.05) were “the right thing to do.” On other Middle East questions, however, professors who rated themselves as regional experts were no more hawkish, such as on the decision of whether to fund Syrian rebels to topple Bashar Assad. And contra the narrative that institutions closer to power select individuals for their perceived expertise, none of the professors who describe themselves as Middle East experts reported working for government compared to 14.7 percent of other professors. For some reason, Middle East expertise tends to be different than expertise for other regions, a topic that deserves further study, and may reflect the large amounts of foreign money involved.

In other areas, self-described expertise fails to predict MI among TTEs. Those working for think tanks were more likely than professors both to be militant internationalists and to view themselves as regional experts, but TTEs who regard themselves as experts on various regions are no more likely than their other think tank colleagues to favor hawkish policies there. Even on the Middle East, TTEs who view themselves as regional experts favor no more or less hawkish policies. The most salient feature of hawks is not their expertise, but their desire to influence policy. Among self-described experts on China (p < 0.01), the Middle East (p < 0.01), East Asia (p < 0.01), and Russia (p < 0.001), TTEs are significantly more likely than professors to value policy influence. Together, these results offer strong empirical support for a self-selection mechanism in which hawks flock to positions of power to maximize their policy impact compared to the alternative explanation in which institutions select hawks for their apparent expertise.

We also consider another knowledge-based institution-selection explanation. Because TTEs are more likely than professors to both rate themselves as regional experts and hold hawkish views, we investigated whether institutions closer to power select out nonexperts for their naive views of foreign adversaries. Jervis (2017) notes that foreign policy differences are often driven by variation in beliefs about the intentions of other actors. It is therefore theoretically plausible that institutions closer to power prefer self-described experts if their expertise provides insight into the aggressive intentions of foreign adversaries. As TTEs are more likely to self-identify as experts, a knowledge-based theory of the difference between TTEs and professors would anticipate finding that regional expertise predicts more hawkish views because studying a region supplies a clearer understanding of adversary intentions. Specifically, this model would predict that self-described experts are more likely to view adversaries as aggressive and to therefore favor hawkish policies. In contrast, the self-selection model would predict that those who pursue employment at think tanks regardless of their expertise are more likely to view adversaries as aggressive and hold hawkish views.

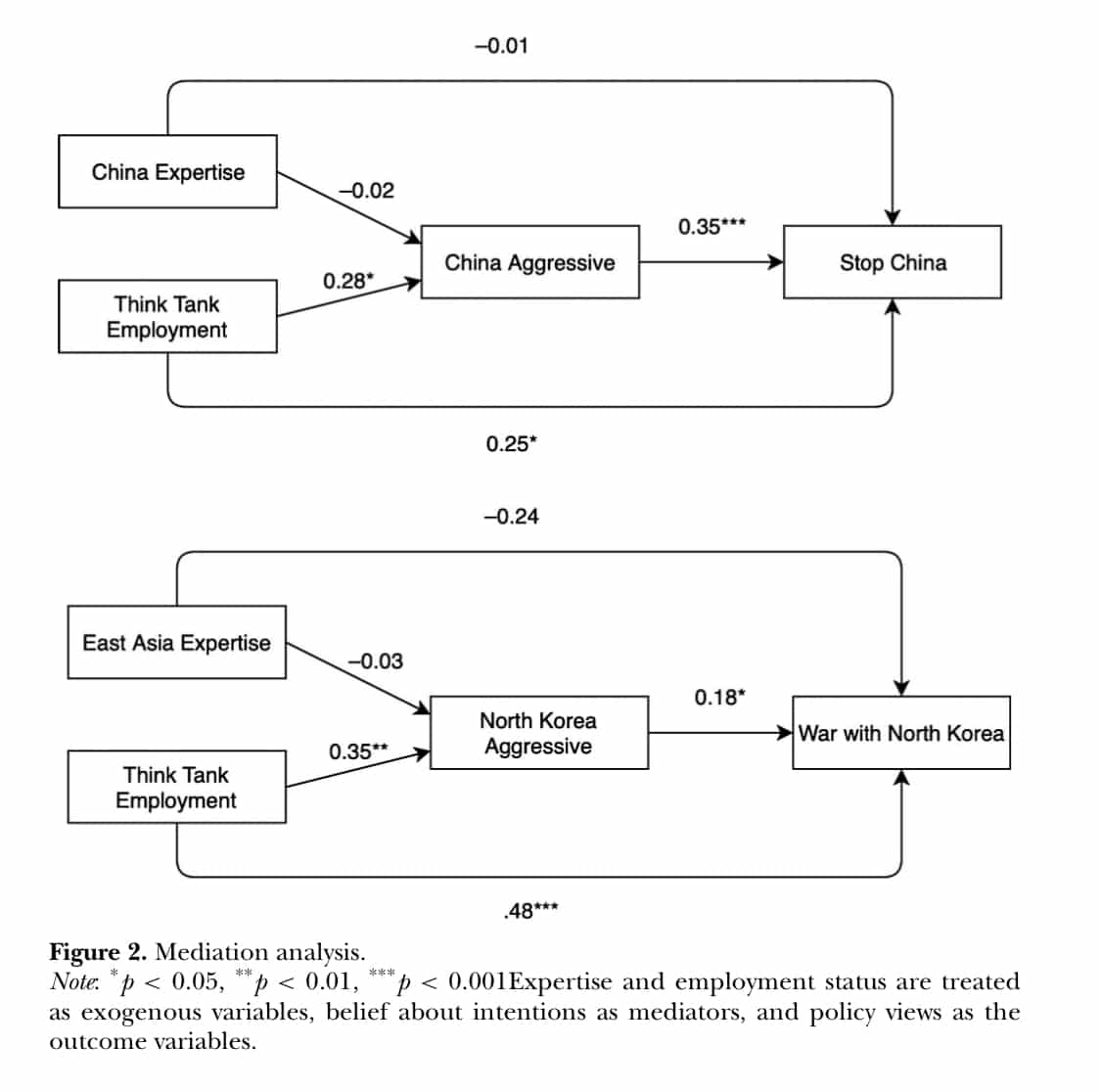

Figure 2 presents results from two path analyses Mackinnon and Fairchild 2009). This type of multiple regression analysis enables researchers to estimate both the magnitude and the significance of causal connections between variables. It is particularly useful for comparing competing narratives with different independent or exogenous variables in which a mediating variable is thought to potentially affect the dependent variable in one or more causal story (Bryman and Cramer 1992. The exogenous variables are dichotomous measures of whether the respondent identified as an expert on the region in question as well as whether the respondent worked in a think tank. The mediating variable is how aggressive respondents viewed the relevant foreign country on a seven-point scale from “strongly believe they are defensive oriented” (1) to “strongly believe they are aggressive” (7). The dependent variable is the hawkishness of the respondent for the relevant policy issue area.

Figure 2 compares the effects of our two independent variables on preferences toward two countries for illustrative purposes—China and North Korea—and the mediating role of their perceived aggressiveness. In the first analysis, employment status and expertise in China are the exogenous variables, assessments of the degree to which China is an aggressive actor is a mediator, and whether the United States should do what it can to stop China is the outcome of interest. The same analysis is performed for North Korea, with specialization in East Asia as the relevant measure of expertise. Standard errors and statistical significance are calculated through the bootstrap method with 200 iterations.

For both China and North Korea, expertise neither predicts views of the aggressiveness of the potential adversary nor supports for a more hawkish stance against it. Think tank employment, in contrast, affects both perceptions of the adversary and policy preferences. Interestingly, most of the effects of think tank employment is not mediated through beliefs about the aggressive intentions of the actor, but rather operates directly. In the case of North Korea, for example, think tank employment leads to almost half a standard deviation increase in hawkishness directly, but only a negligible 0.06 standard deviation increase indirectly through changing perceptions of the intentions of the Kim regime. These path analyses accord with other findings in the survey data, such as that TTEs with PhDs are still more hawkish (β = 0.31, p < 0.10) than professors. TTEs and professors apparently have divergent views on adversaries even after undergoing similar educational experiences.

As a final comparison between the self-selection and institution-selection mechanisms, we investigated whether TTEs become more hawkish over time. If so, then perhaps TTEs become more hawkish as they gain a better understanding of our foreign adversaries or think tanks select people to cultivate their policy preferences. The survey is not longitudinal, but we are able to compare the answers of older TTEs to younger ones. Consistent with the self-selection model, younger TTEs are no less hawkish than older ones. If TTEs became more hawkish due to information received, we would expect to observe a positive relationship between more seasoned analysts and those favoring intervention abroad. The absence of this empirical relationship runs counter to the explanation that the institutions themselves shape employee hawkishness as opposed to the other way around.

Research and Policy Implications

Despite a widespread view of their importance in US foreign policy-making, think tanks have historically been neglected within the field of IR. According to one study, no articles specifically on the topic of think tanks appeared in the American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, or Journal of Politics from 1975 to 2005 (Rich 2004, 8). Increasingly, several prominent IR scholars have called for US foreign policy restraint and criticized the think tank community for its interventionist policy positions (e.g., Bacevich 2013; Posen 2014; Porter 2018).9See Smeltz et al. (2017) for the contrary view that “the blob” reflects public opinion. Yet, this perception that TTEs are more hawkish than their academic counterparts has remained contested and anecdotal (Walt 2018). Given the presumed influence of think tanks on the direction of US foreign policy, it is surprising that such scant empirical research has investigated what they actually believe.

Our study is the first to employ survey methods to quantify the foreign policy beliefs of TTEs relative to IR professors. The data demonstrate substantial variation within both respondent groups. In general, however, the survey reveals that TTEs are indeed more likely than professors to be militant internationalists and to support hawkish policies throughout the world. Although isolationism is unpopular among both classes of opinion-makers, TTEs are consistently more supportive than professors employing US military force abroad.

This paper also sheds light on why. The data lend preliminary support for a selfselection mechanism in which hawks are more inclined to pursue positions of power to maximize their policy influence. This parsimonious mechanism has explanatory value for explaining differences in foreign policy beliefs both between and within respondent groups. Hawks appear to gravitate to think tanks because they offer greater opportunities for impacting policy. The survey reveals that TTEs care more than professors do about policy impact, and this incentive structure is associated with more hawkish views. Relatively hawkish think tanks are not only located closer to Capitol Hill, but more frequently engage in activities to impact policy, such as by appearing in the media to advocate a policy position. When hawkish, professors are more likely to spend time away from the proverbial ivory tower to pursue jobs in think tanks and especially in the federal government, which afford them superior access points to translate their foreign policy preferences into action.

In contrast, we observe weaker empirical support for a reverse selection mechanism in which institutions closer to power select hawks for their apparent expertise. Because measuring expertise is not straightforward (Tetlock 2017), we operationalized the concept in multiple ways. Neither PhD obtainment nor foreign language skill is associated with MI. And for both respondent groups, self-described experts are generally no more hawkish toward the corresponding regions of the world. Because TTEs are more likely than professors to rate themselves as regional experts and hold hawkish views, we also examined the related possibility that institutions closer to power select out nonexperts for their starry-eyed views of foreign adversaries. The perception that a foreign adversary harbors aggressive intentions indeed predicts hawkish stances toward it, as prior research would anticipate (Jervis 2017). However, our path analysis reveals stronger support for a self-selection than institution-selection mechanism; unlike the choice of working in a think tank, expertise is unassociated with either perceptions of aggressive intent or hawkish stances. Regardless of their expertise, TTEs are more likely than professors to view adversaries as aggressive and to favor more hawkish policies against them. Although the perception of aggressive intent mediates hawkishness for TTEs, the relationship is largely independent of it. TTEs do not become more hawkish as they gain expertise about foreign adversaries, adding to the evidence that employees select think tanks to translate their hawkish policy preferences into action. Although our data support a self-selection explanation, we cannot definitely rule out the possibility of a particular type of institution-selection explanation in which think tank employers simply prefer hiring hawks independent of their expertise and experience. If so, then demand might influence supply, with less hawkish scholars concluding that their professional options in the policy-making world are limited, thus favoring an academic career. This complex process through which the biases of institutions are ultimately the cause of the disparities is consistent with the data, which nonetheless implies that self-selection at least operates as a proximate cause.

Future studies with larger samples, panel data, and interviews for process-tracing can further quantify what TTEs and IR professors believe about the world as well as elucidate why they pursued their chosen career path. Our paper indicates that scholars flock to think tanks for the policy relevance, but surely other factors contribute. Additional research should be conducted not only comparing professors to TTEs, but also to gain better insight into their within-group differences. Specifically, the professor sample is restricted to tenured and tenure-track scholars in political science departments at research universities, but can be enlarged to include public policy professors who may overlap more with TTEs in their survey responses. Enlarging the sample may also find that TTEs who participate in the revolving door with government are generally more hawkish than TTEs who remain on the sidelines. Our data do not establish this finding perhaps because the hawkishness of the TTE sample restricts the range of the dependent variable (Sackett and Yang 2000). In addition to large-n work, process tracing would be useful for further elucidating determinants of participation in the revolving door. Similarly, additional research should further probe differences between think tanks, particularly ones with different funding sources. Given this concern, we re-ran the analyses without RAND because this think tank has a special status as a federally funded research and development center (FFRDC).10For a think tank, RAND scores relatively low on militant internationalism, but still higher than professors. We also reran the models without Cato because of its relative dovishness. Our findings appear robust in the sense that excluding such outliers from the analysis does not substantially affect the main results. More fundamentally, future research should try to resolve the question of why hawks appear to prioritize policy influence in the first place.

This research has important policy implications. A common complaint of IR professors is that they are not “policy relevant”. This criticism is largely unfounded, particularly for the growing minority of IR scholars who self-consciously seek to “bridge the gap” with the policy world (e.g., Jentleson 2015). Our data suggest that increasing the power of the academy relative to that of think tanks would lead American foreign policy in a less interventionist direction, but only if more doves continue to pursue positions closer to power.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Sercan Canbolat for his insightful comments on earlier drafts.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information is available at the Foreign Policy Analysis data archive.

References

ABELSON, DONALD E. 1996. American Think-Tanks and Their Role in US Foreign Policy. New York: Macmillan Press.

———. 2000. “Do Think Tanks Matter? Opportunities, Constraints and Incentives for Think Tanks in Canada and the United States.” Global Society 14 (2): 213–36.

———. 2018. Do Think Tanks Matter? Assessing the Impact of Public Policy Institutes. Montreal: McGillQueen’s University Press.

ABRAHMS, MAX, AND JOHN GLASER. 2018. “The Pundits Were Wrong about Assad and the Islamic State: As Usual, They’re Not Willing to Admit it.” Los Angeles Times.

ACHARYA, AMITAV. 2016. “Advancing Global IR: Challenges, Contentions, and Contributions.” International Studies Review 18 (1): 4–15.

ARSHED, NORIN. 2017. “The Origins of Policy Ideas: The Importance of Think Tanks in the Enterprise Policy Process in the UK.” Journal of Business Research 71: 74–83.

AVEY, PAUL C., AND MICHAEL C. DESCH. 2014. “What Do Policymakers Want from Us? Results of a Survey of Current and Former Senior National Security Decision Makers.” International Studies Quarterly 58 (2): 227–46.

BACEVICH, ANDREW J. 2013. The New American Militarism: How Americans Are Seduced by War. New York: Oxford University Press.

BAUM, MATTHEW A., AND PHILIP B.K. POTTER. 2008. “The Relationships between Mass Media, Public Opinion, and Foreign Policy: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis.” Annual Review of Political Science 11: 39–65.

BEAUCHAMP, ZACK. 2017. “Why Democrats Have No Foreign Policy Ideas.” Vox. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.vox.com/world/2017/9/5/16220054/democrats-foreign-policy-think-tanks.

BINDERKRANTZ, ANNE S., HELENE H. PEDERSEN, AND JAN BEYERS. 2017. “What Is Access? A Discussion of the Definition and Measurement of Interest Group Access.” European Political Science 16: 306–21.

BRANDS, HAL. 2017. “Why Scholars and Policy Makers Disagree.” The American Interest. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.the-american-interest.com/2017/06/05/why-scholars-and-policymakersdisagree/.

BRYMAN, ALAN, AND DUNCAN CRAMER. 1992. “Quantitative Data Analysis for Social Scientists.” Estudios Geográficos 53 (207): 347.

BUSBY, JOSHUA W., AND JONATHAN MONTEN. 2008. “Without Heirs? Assessing the Decline of Establishment Internationalism in US Foreign Policy.” Perspectives on Politics 6 (3): 451–72.

BYMAN, DANIEL, AND MATTHEW KROENIG. 2016. “Reaching beyond the Ivory Tower: A How to Manual.” Security Studies 25 (2): 289–319.

COGGINS, BRIDGET. 2019. “A Cult without Member and Influence without Access.” Texas National Security Review. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://tnsr.org/roundtable/book-review-roundtable-cult-ofthe-irrelevant/.

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS. 2019. “International Affairs Fellowship for Tenured International Relations Scholars.” Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/fellowships/international-affairsfellowship-tenured-international-relations-scholars/.

DESCH, MICHAEL C. 2019. Cult of the Irrelevant: The Waning Influence of Social Science on National Security. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

DHIRAJ, AMARENDRA BHUSHAN. 2017. “The 100 Most Influential Think Tanks in the World for 2017.” CEO World. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://ceoworld.biz/2017/01/31/100-influential-think-tanksworld-2017/.

DRAPER, ROBERT. 2021. To Start a War: How the Bush Administration Took America into Iraq. London, England: Penguin.

FAZAL, TANISHA M. 2014. “The World’s Newest War in the World’s Newest State.” Accessed November 25, 2022. http://politicalviolenceataglance.org/2014/01/06/the-worlds-newest-war-inthe-worlds-newest-state/.

FEULNER, EDWIN J. 1985. “Ideas, Think-Tanks and Governments.” Quadrant 29 (11): 22–26.

FRIEDMAN, BENJAMIN H. 2016. “How Much Defense Is Enough? The Outlier’s Take.” Cato. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.cato.org/blog/how-much-defense-enough-outliers-take.

FRIEDMAN, BENJAMIN H., AND JUSTIN LOGAN. 2016. “Why Washington Doesn’t Debate Grand Strategy.” Strategic Studies Quarterly 10 (4): 14–45.

GALLUCCI, ROBERT. 2014. “Academia and the Foreign Policy-Making Process.” Speech.

GOLDGEIER, JAMES, AND BRUCE JENTLESON. 2015. “How to Bridge the Gap between Policy and Scholarship.” War on the Rocks, June 29. Available at Accessed November 25, 2022. https://warontherocks.com/2015/06/how-to-bridge-the-gap-between-policy-and-scholarship/.

GRAY, COLIN S. 1971. “What RAND Hath Wrought.” Foreign Policy 4: 111–29.

GREEN, JESSICA F., AND THOMAS N. HALE. 2017. “Reversing the Marginalization of Global Environmental Politics in International Relations: An Opportunity for the Discipline.” PS: Political Science & Politics 50 (2): 473–79.

HAASS, RICHARD N. 2002. “Think Tanks and US Foreign Policy: A Policy-Makers Perspective.” US Foreign Policy Agenda 7 (3): 5–8.

HALSE, CHRISTINE, AND SUSAN MOWBRAY. 2011. “The Impact of the Doctorate.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (5): 513–25.

HIGGOTT, RICHARD, AND DIANE STONE. 1994. “The Limits of Influence: Foreign Policy Think Tanks in Britain and the USA.” Review of International Studies 20 (1): 15–34.

HODGE, NATHAN. 2010. “The Nation: Who Drives the Think Tanks?” NPR. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=124760902.

HOLSTI, OLE R., AND JAMES N. ROSENAU. 1988. “The Domestic and Foreign Policy Beliefs of American Leaders.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 32 (2): 248–94.

———. 1990. “The Structure of Foreign Policy Attitudes among American Leaders.” The Journal of Politics 52 (1): 94–125.

HOROWITZ, MICHAEL. 2015. “What is Policy Relevance?” War on the Rocks. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://warontherocks.com/2015/06/what-is-policy-relevance/.

IYENGAR, SHANTO, AND ADAM SIMON. 1993. “News Coverage of the Gulf Crisis and Public Opinion: A Study of Agenda-Setting, Priming, and Framing.” Communication Research 20 (3): 365–83.

JENTLESON, BRUCE W. 2015. “The Bridging the Gap Initiative and Programs.” PS: Political Science & Politics 48 (S1): 108–14.

JENTLESON, BRUCE W., AND ELY RATNER. 2011. “Bridging the Beltway–Ivory Tower Gap.” International Studies Review 13 (1): 6–11.

JERVIS, ROBERT. 2017. “Perception and Misperception in International Politics.” In Perception and Misperception in International Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

KERTZER, JOSHUA D., KATHLEEN E. POWERS, BRIAN C. RATHBUN, AND RAVI IYER. 2014. “Moral Support: How Moral Values Shape Foreign Policy Attitudes.” The Journal of Politics 76 (3): 825–40.

KESKINGÖREN, TUGRUL, AND PATRICK R. HALPERN. 2005. “Behind Closed Doors: Elite Politics, Think Tanks, and US Foreign Policy.” Insight Turkey 7 (2): 99–114.

KRISTOF, NICHOLAS. 2014. “Professors, We Need You.” New York Times. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/16/opinion/sunday/kristof-professors-we-need-you.html.

LANGBERT, MITCHELL. 2018. “Homogenous: The Political Affiliations of Elite Liberal Arts College Faculty.” Academic Questions 31 (2): 186–97.

LANGBERT, MITCHELL, ANTHONY J. QUAIN, AND DANIEL B. KLEIN. 2016. “Faculty Voter Registration in Economics, History, Journalism, Law, and Psychology.” Econ Journal Watch 13 (3): 422–51.

LEVINSON, CHAD. 2021. “Partners in Persuasion: Extra-Governmental Organizations in the Vietnam War.” Foreign Policy Analysis 17 (3): orab021.

LIPTON, ERIC, BROOKE WILLIAMS, AND NICHOLAS CONFESSORE. 2014. “Foreign Powers Buy Influence at Think Tanks.” New York Times. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/07/ us/politics/foreign-powers-buy-influence-at-think-tanks.html.

LONG, JAMES D., DANIEL MALINIAK, SUSAN M. PETERSON, AND MICHAEL J. TIERNEY. 2015. “Knowledge without Power: International Relations Scholars and the US War in Iraq.” International Politics 52 (1): 20–44.

MACKINNON, DAVID P., AND AMANDA J. FAIRCHILD. 2009. “Current Directions in Mediation Analysis.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 18 (1): 16–20.

MAGGIOTTO, MICHAEL A., AND EUGENE R. WITTKOPF. 1981. “American Public Attitudes toward Foreign Policy.” International Studies Quarterly 25 (4): 601–31.

MALINIAK, DANIEL, SUSAN PETERSON, AND MICHAEL J. TIERNEY. 2019. “Policy-Relevant Publications and Tenure Decisions in International Relations.” PS: Political Science & Politics 52 (2): 318–24.

MCGANN, JAMES G. 2016. The Fifth Estate: Think Tanks, Public Policy, and Governance. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

———. 2019. “2018 Global Go to Think Tank Index Report.” Accessed November 25, 2022. https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=think_tanks.

MCNUTT, KATHLEEN, AND GREGORY MARCHILDON. 2009. “Think Tanks and the Web: Measuring Visibility and Influence.” Canadian Public Policy 35 (2): 219–36.

MEDVETZ, THOMAS. 2008. “Think Tanks as an Emergent Field.” Social Science Research Council, New York. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/51289a2fe4b006d82fb7c4ff/t/ 517b1824e4b077614f0f25c9/1367021604433/Medvetz.2008.Think+Tanks+as+an+Emergent+ Field.pdf.

———. 2010. “‘Public Policy is Like Having a Vaudeville Act’: Languages of Duty and Difference among Think Tank-Affiliated Policy Experts.” Qualitative Sociology 33 (4): 549–62.

MISZTAL, BARBARA A. 2012. “Public Intellectuals and Think Tanks: A Free Market in Ideas?” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 25 (4): 127–41.

NYE, JOSEPH. 2009. “Scholars on the Sidelines.” Washington Post, April 13. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/04/12/AR2009041202260.html.

PICARD, ROBERT. 2019. “GEODIST: Stata Module to Compute Geographical Distances.” Accessed November 25, 2022. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457147.html.

PORTER, PATRICK. 2018. “Why America’s Grand Strategy Has Not Changed: Power, Habit, and the US Foreign Policy Establishment.” International Security 42 (4): 9–46.

POSEN, BARRY R. 2014. “Restraint.” In Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

RHODES, BEN. 2019. The World as It Is: A Memoir of the Obama White House. New York, NY: Random House Trade Paperbacks.

RICH, ANDREW. 2001. “US Think Tanks and the Intersection of Ideology, Advocacy and Influence.” Nira Review 8 (1): 54–59.

———. 2004. Think Tanks, Public Policy, and the Politics of Expertise. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

ROSENTIEL, TOM. 2008. “Public Attitudes Toward the War in Iraq: 2003–2008.” Pew Research Center. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/2008/03/19/public-attitudes-toward-thewar-in-iraq-20032008/.

ROTHMAN, JOSHUA. 2014. “Why Is Academic Writing So Academic.” The New Yorker, February 20. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/why-is-academic-writing-soacademic.

SACKETT, PAUL R., AND HYUCKSEUNG YANG. 2000. “Correction for Range Restriction: An Expanded Typology.” Journal of Applied Psychology 85 (1): 112–18.

SCHLAFMAN, SHIRLEY GRINSTEAD. 1967. “An Isolationist Faces War: A Historical Review of the Foreign Policy Views of Senator Robert A. Taft between 1939 and 1945.” PhD dissertation, The Ohio State University.

SHAPIRO, MARGARET. 1984. “Mandate II.” Washington Post, November 22. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1984/11/22/mandate-ii/ee2ede6b-86c0- 4180-8e94-3d4a533a9b72/?utm_term=.5ca09de7f8e4.

SHEEHAN, KIM BARTEL. 2001. “E-mail Survey Response Rates: A Review.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 6 (2): JCMC621.

SMELTZ, DINA, KARL FRIEDHOFF, CRAIG KAFURA, JOSHUA BUSBY, JONATHAN MONTEN, AND JORDAN TAMA. 2017. “The Foreign Policy Establishment or Donald Trump: Which Better Reflects American Opinion?” Chicago Council on Global Affairs. Accessed November 25, 2022. https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/ publication/foreign-policyestablishment-or-donald-trump-which-better-reflects-american-opinion.

SMITH, JAMES A. 1989. “Think Tanks and the Politics of Ideas.” In The Spread of Economic Ideas, edited by David C. Colander and Alfred William Coats, 175–94. New York: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1993. Idea Brokers: Think Tanks and the Rise of the New Policy Elite. New York: Simon and Schuster.

STONE, DIANE. 2013. Capturing the Political Imagination: Think Tanks and the Policy Process. London: Routledge.

TETLOCK, PHILIP E. 2017. Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

UNITED NATIONS. 2003. Thinking the Unthinkable: From Thought to Policy: The Role of Think Tanks in Shaping Government Strategy. New York, NY: United Nations Press.

WALT, STEPHEN M. 2018. The Hell of Good Intentions: America’s Foreign Policy Elite and the Decline of US Primacy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

WEAVER, R. KENT, AND JAMES G. MCGANN, eds. 2017. “Think Tanks and Civil Societies in a Time of Change.” In Think Tanks and Civil Societies, 1–36. New York: Routledge.

WEIDENBAUM, MURRAY. 2010. “Measuring the Influence of Think Tanks.” Society 47 (2): 134–37.

WEMHEUER-VOGELAAR, WIEBKE, NICHOLAS J. BELL, MARIANA NAVARRETE MORALES, AND MICHAEL J. TIERNEY. 2016. “The IR of the Beholder: Examining Global IR Using the 2014 TRIP Survey.” International Studies Review 18 (1): 16–32.

WOODWARD, BOB. 2011. Obama’s Wars. New York: Simon and Schuster.

ZALLER, JOHN R. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

ZARAKOL, AYSE¸ . 2017. “TRIPping Constructivism.” PS: Political Science & Politics 50 (1): 75–78.