As this article shows, technology creates more jobs than it destroys – despite the claims to the contrary, innovation is a job creator, not a job demolisher”. But this issue keeps receiving attention. For example, Bill de Blasio’s “robot tax” idea and Andrew Yang’s insistence that “robot compensation” is necessary. Both proposals are misleading and harmful. Innovation is the real engine for economic growth, employment and social development.

According to a report by the Brookings Institution titled “Automation and Artificial Intelligence: How Machines Affect People and Places”, automation is a direct threat to 25 percent (36 million) of jobs in the US. Oxford University economists Carl Frey and Michael Osborne agreed. They argue that 40 percent of all jobs are at risk of being lost to computers in the next two decades.

When scholars are creating waves, politicians are always ready to surf them!

It’s no wonder Democratic presidential candidate Bill de Blasio recently published an op-ed titled “Why American Workers Need to Be Protected From Automation” where he proposes a “Robot Tax.” Businesses that “eliminate jobs through increased automation” would be forced to pay additional taxes for every employee replaced by a robot.

He is not alone! His fellow aspirant to the presidential chair, Andrew Yang, has claimed that “automation is a threat to the country.” His proposal is not a tax, but an aid (universal basic income) for every American adult in order to compensate for the prospective job losses due to automation.

Are they right about the need for workers’ protection?

Absolutely not!

A Door Closes…Others Open

Blasio and Yang are not exactly inventing the wheel. They are exploring pessimistic pre-existing scenarios.

A survey by Pew Research Internet found that Americans are roughly twice as likely to express worry (72%) than enthusiasm (33%) about a future in which innovations are capable of doing tasks that are currently done by humans. Why are so many people afraid of technology?

It is likely because people have been told they will be replaced by robots! Actually, this fear has always haunted workers. In 1930 the notorious economist John Maynard Keyes wrote an essay suggesting that there would be mass unemployment following automation of manufacturing, after all, a single machine can replace dozens of workers. Was he correct? Of course not!

If technology blew some jobs away, somehow it put many others in the place. Keynes (as well as Blasio and Yang) forgot that the stock of work in the economy is not fixed. Where a door is closed, others (usually bigger ones) are opened. Don’t believe me? See the figures ahead!

Soon after Keyne’s article was published, unemployment rate plummeted from 22 percent in 1932 to 1.2 percent in 1942 – nowadays (when we have more automation than ever) it is around 4 percent. The funniest thing is that employment in manufacturing truly dropped from 38 percent of the workforce in 1948 to 8 percent by 2012, but jobs created in new areas more than compensated the losses.

Technology Changes the Way We Work

In 1901, 6.15 percent (200,000 people) of the (32.5 million) population in England and Wales was engaged in washing clothes. Then, electricity and indoor plumbing were invented These technologies made the automatic washing machine possible. The drudgery of hand washing was left in the past. By 2011, just 0.06 percent (35,000 people) of the (56.1 million) population worked in the sector, most in commercial laundries.

It looks like we lost a lot of jobs (165,000), doesn’t it? It only seems that way!

As the German economist Werner Sombart argued, the destruction of the old opens the way for creation of the new. For example, shortage of wood led to the use of coal. Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter would go even further in claiming that progress comes from innovation, which is responsible for creating new markets that are far more profitable and effective than the ones it destroys.

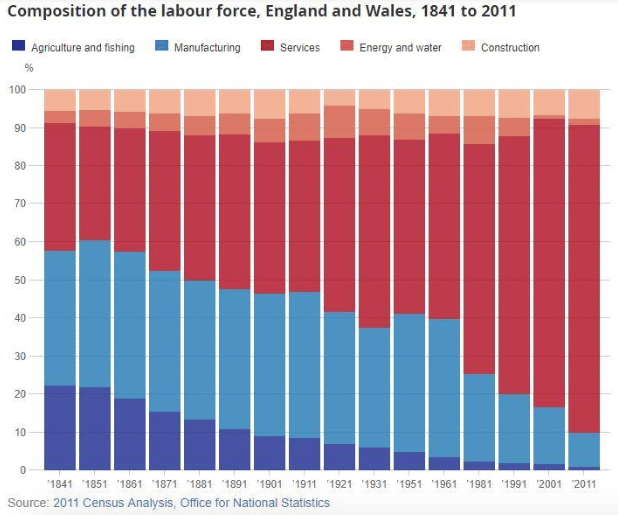

Data from census records on employment in England strengths these statements: if in 1841 most people (35.5 percent) worked in manufacturing, by 2011 this share has decreased to 8.9 percent, while the number of workers in the service industry boosted to 81.1 percent.

In simple words: what we lose in one industry, we gain in another. Check this out in the chart below.

What innovation does is fundamentally change the labor market structure – not simply take away jobs.

What Jobs Do We Want to Keep?

There is no point in denying that, in some sectors, technology costs jobs through the process of creative destruction (well-explained by quoted economist Joseph Schumpeter). New sectors attract resources away from old ones. New firms take business away from established ones. New technologies make existing skills and machines obsolete.

However, in a vast number of cases, innovation merely eases our workload or allows us to stop doing what we do not want to do anymore (usually something dull, dirty or dangerous). Then, the question is whether the jobs lost are really jobs we want to keep.

Allow me to illustrate. In 1841 around 20 percent of workers were concentrated in agriculture and fishing. This number declined to less than 1 percent by 2011. Now, we can have our dinner without taking part in the harvest. But what about safety? Today, robotic technology makes up 29 percent of welding applications, freeing humans from work with chemical reactions (hazardous fumes and ultraviolet light) and extremely hot temperatures. This is just one example of how robots can supplement our roles by making them less dangerous than before.

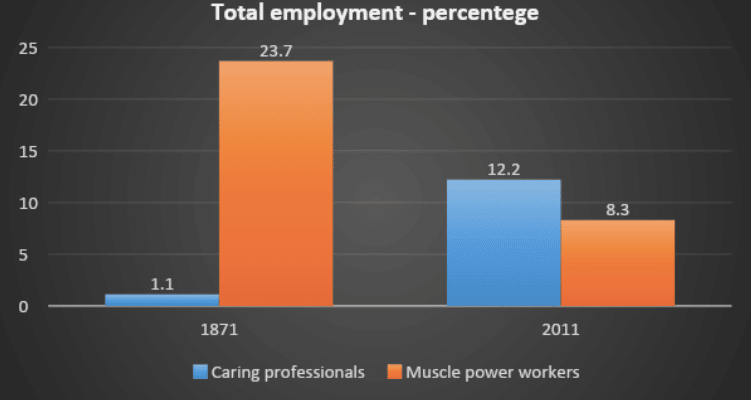

Indeed, the last few centuries have witnessed a profound shift in the labor market, which is switching from muscle power activities (agricultural workers, cleaners, domestic servants, routine factory operatives, construction laborers and miners) to caring professions (health and teaching professionals, welfare and care home workers).

No matter what apocalyptic prophets say, we cannot predict how technology will shape tomorrow’s society. But we definitely can read the trends and expect that automation gets rid of the most laborious and less satisfactory jobs and makes room for new cognitive or manual non-routine occupations. It is a good scenario, isn’t it?

A Game Where Everybody Wins

Innovation improves living standard for everyone, particularly the poor, and creates more jobs.

For instance, the grounding-break inventions of the Industrial Revolution (mass production machines) lowered costs and prices, enabling working class consumers to purchase things that before only aristocrats had access to and that today we take for granted (sugar, tea, coffee, watches, porcelain, glass, curtains, colorful clothes, etc.).

This trend remained in contemporary times. As the study by economists at the consultancy Deloitte indicates, between 1950 and 2014, the price of food plummeted from 34.8 to 11.3 percent (in the retail price index basket); clothing and footwear followed the same path: 9.7 to 4.5 percent. In 1948, a 16-inch TV cost $795 (equivalent to $12,000 today) – roughly a quarter of the average annual salary in the US (only the rich could afford it); nowadays a top of the range TV can be bought for less than $1,000 (anyone can have one on their wall).

Moreover, declines in prices leave more money to be spent on additional goods (especially non-essentials), what increases the demand – including in “non-technological” occupations.

The Myth of Low-Skilled Jobs Disappearing

Despite what we have just seen, perhaps the main point is still troubling: the fear of being left behind. People are afraid of being losers today in this process of creative destruction. They fear losing the jobs they currently have and not being able to find another one. This is an understandable concern.

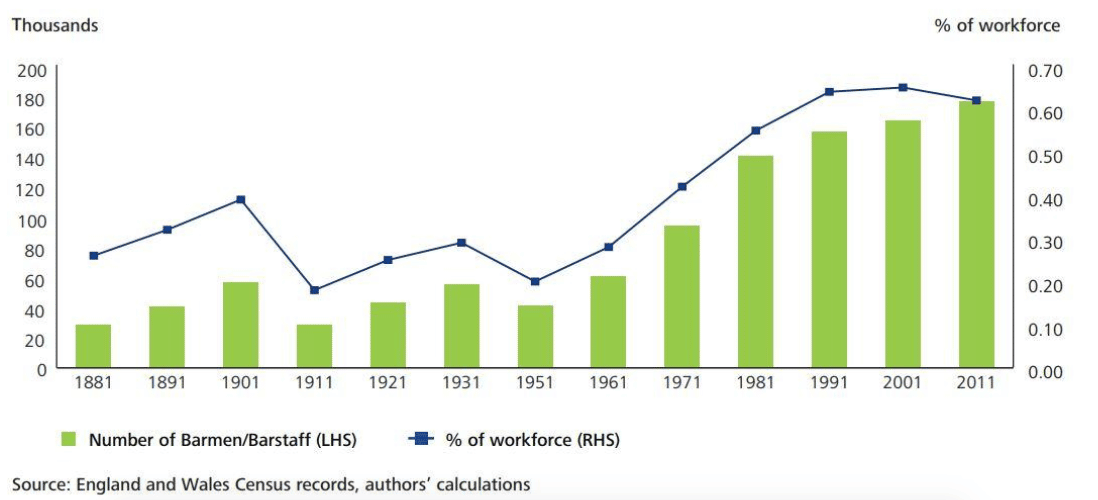

It turns out that it is a myth that technological development will leave behind nothing but high-skilled jobs. Historical data show a different picture. Innovations-driven declines in prices lead to an increase in consumer spending power, which, in turn, creates new (immediate) demand and new jobs in “normal” sectors of the economy (not only in high-skilled ones).

For instance, in England and Wales, while the Industrial Revolution was scattering its effects, the barbers built their “empire” – in 1871, there was one barber for every 1,793 citizens; by 2011 this relation was one for every 287. Not enough? The number of people employed in bars rose four-fold between 1951 and 2011, whilst technological development was spreading (and roaring) at a fast pace (see the chart below).

Yes, rising incomes enable consumers to spend more on personal (non-essential) goods and services such as drinks, happy-hours, grooming and hairdressing. It is hardly a surprise that PwC predicts that by 2030 innovation (software and robotics) is likely to add $15.7 trillion to the global GDP, boosting it by about 14 percent.

Surprising Long-Term effects

Most of the direct benefits of technology are relatively clear and well-known – related to overpassing human limitations. Less known are the long-term effects, often distant from the original purpose (beneficial side-effects). I will provide some examples.

Car ownership: Not a big deal, huh? First, it has allowed people to live in suburbs, pay cheaper rents and work far away from their houses. Furthermore, as the Nobel Laureate Herbert Simon noted, before the Car Era, one of the most important skills a doctor could have was the ability to ride a horse to reach his patients. Cars enabled medical progress. We now have big hospitals, health centers and equipped doctor’s offices only because patients can travel to them.

Rising female workforce participation is a very strong contemporary claim. Fortunately, married women’s participation in the formal labor market increased dramatically. It rose from around 2 percent in 1880 to over 70 percent in 2000 in the US. This process was undisputedly facilitated by inventions such as the contraceptive pill and the development of labor-saving domestic technologies and convenience food.

Computers and ease of communication permitted the arising of new means of long-distance learning (such as video broadcasting). Nowadays, people from the countryside can access and afford relatively high-quality education in order to compete for well-paying jobs. Instruction required to grab better positions can be reached by almost anyone, almost anywhere.

Technology is a wide-ranging revolution.

Leave Technology Alone

The conclusion is simple and clear. Over time, technology (and its daughter, automation) has improved living conditions, made our lives easier, created new sectors and jobs, allowed people far from big centers to access education, made female workforce participation feasible, boomed the economy and increased wealth. Even better, it will continue to do that if we allow it to do so.

A new tax on robots or a compensation-aid because of automation would be nothing more than a disincentive to innovation. that would be bad news for workers.

Jean Vilbert holds a Bachelors and a Masters of Law. He is currently a Judge, Writer and Professor of Law and Economics in São Paulo, Brazil. You can reach him on Twitter.