The anniversaries of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki present an opportunity to demolish a cornerstone myth of American history—that those twin acts of mass civilian slaughter were necessary to bring about Japan’s surrender, and spare a half-million U.S. soldiers who’d have otherwise died in a military conquest of the empire’s home islands.

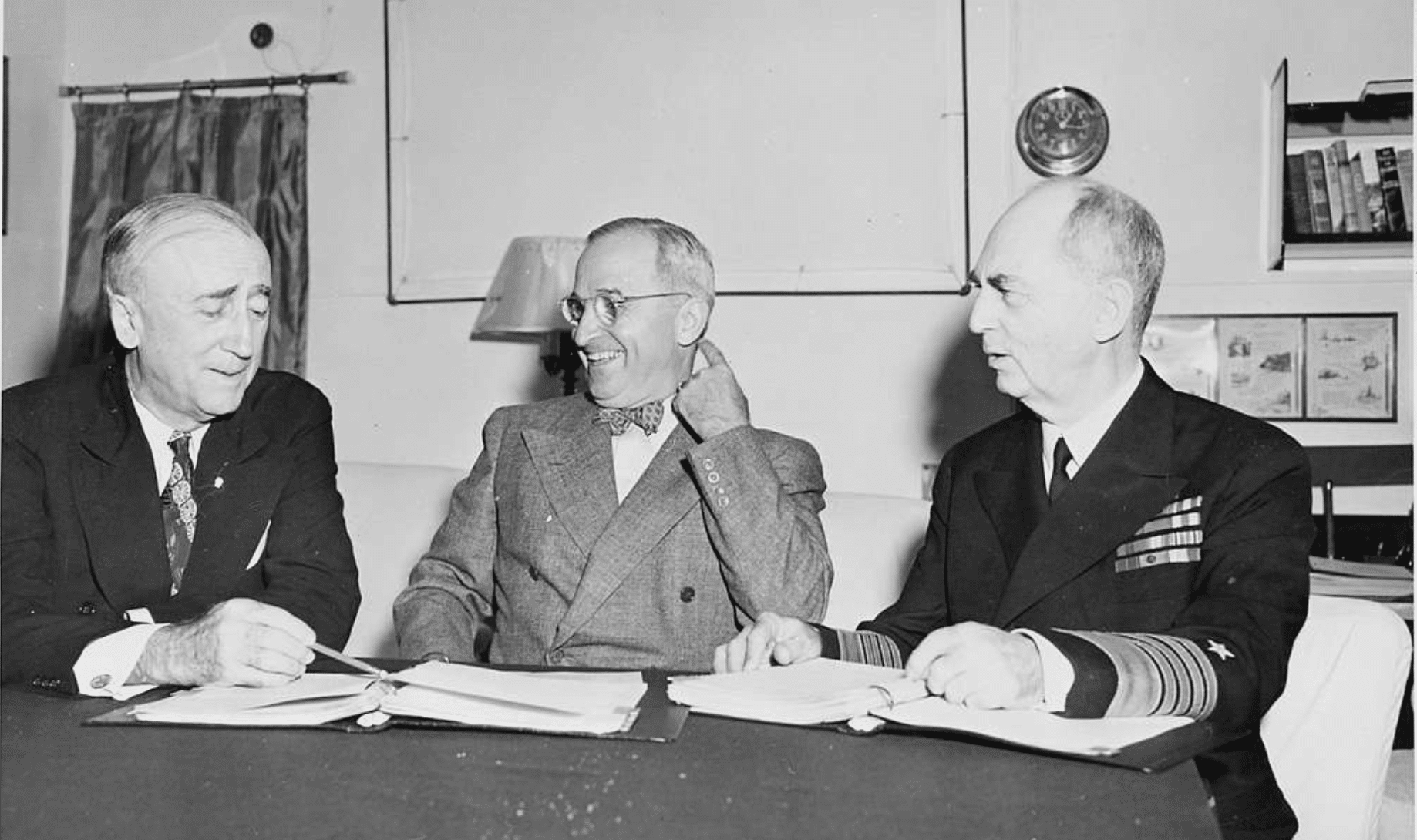

Those who attack this mythology are often reflexively dismissed as unpatriotic, ill-informed or both. However, the most compelling witnesses against the conventional wisdom were patriots with a unique grasp on the state of affairs in August 1945—America’s senior military leaders of World War II.

Let’s first hear what they had to say, and then examine key facts that led them to their little-publicized convictions:

- General Dwight Eisenhower on learning of the planned bombings: “I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and voiced to [Secretary of War Stimson] my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of ‘face.’”

- Admiral William Leahy, Truman’s Chief of Staff: “The use of this barbarous weapon…was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.”

- Major General Curtis LeMay, 21st Bomber Command: “The war would have been over in two weeks without the Russians entering and without the atomic bomb…The atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the war at all.”

- General Hap Arnold, U.S. Army Air Forces: “The Japanese position was hopeless even before the first atomic bomb fell, because the Japanese had lost control of their own air.” “It always appeared to us that, atomic bomb or no atomic bomb, the Japanese were already on the verge of collapse.”

- Ralph Bird, Under Secretary of the Navy: “The Japanese were ready for peace, and they already had approached the Russians and the Swiss…In my opinion, the Japanese war was really won before we ever used the atom bomb.”

- Brigadier General Carter Clarke, military intelligence officer who prepared summaries of intercepted cables for Truman: “When we didn’t need to do it, and we knew we didn’t need to do it…we used [Hiroshima and Nagasaki] as an experiment for two atomic bombs. Many other high-level military officers concurred.”

- Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, Pacific Fleet commander: “The use of atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender.”

Putting out feelers through third-party diplomatic channels, the Japanese were seeking to end the war weeks before the atomic bombings on August 6 and 9, 1945. Japan’s navy and air forces were decimated, and its homeland subjected to a sea blockade and allied bombing carried out against little resistance.

The Americans knew of Japan’s intent to surrender, having intercepted a July 12 cable from Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo, informing Japanese ambassador to Russia Naotake Sato that “we are now secretly giving consideration to the termination of the war because of the pressing situation which confronts Japan both at home and abroad.”

Togo told Sato to “sound [Russian diplomat Vyacheslav Molotov] out on the extent to which it is possible to make use of Russia in ending the war.” Togo initially told Sato to obscure Japan’s interest in using Russia to end the war, but just hours later, he withdrew that instruction, saying it would be “suitable to make clear to the Russians our general attitude on ending the war”—to include Japan’s having “absolutely no idea of annexing or holding the territories which she occupied during the war.”

Japan’s central concern was the retention of its emperor, Hirohito, who was considered a demigod. Even knowing this—and with many U.S. officials feeling the retention of the emperor could help Japanese society through its postwar transition—the Truman administration continued issuing demands for unconditional surrender, offering no assurance that the emperor would be spared humiliation or worse.

In a July 2 memorandum, Secretary of War Henry Stimson drafted a terms-of-surrender proclamation to be issued at the conclusion of that month’s Potsdam Conference. He advised Truman that, “if…we should add that we do not exclude a constitutional monarchy under her present dynasty, it would substantially add to the chances of acceptance.”

Truman and Secretary of State James Byrne, however, continued rejecting recommendations to give assurances about the emperor. The final Potsdam Declaration, issued July 26, omitted Stimson’s recommended language, sternly declaring, “Following are our terms. We will not deviate from them.”

One of those terms could reasonably be interpreted as jeopardizing the emperor: “There must be eliminated for all time the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest.”

At the same time the United States was preparing to deploy its formidable new weapons, the Soviet Union was moving armies from the European front to northeast Asia.

Continue reading this article at Stark Realities with Brian McGlinchey