Blog

Anti-War Blog – The gods of sadism

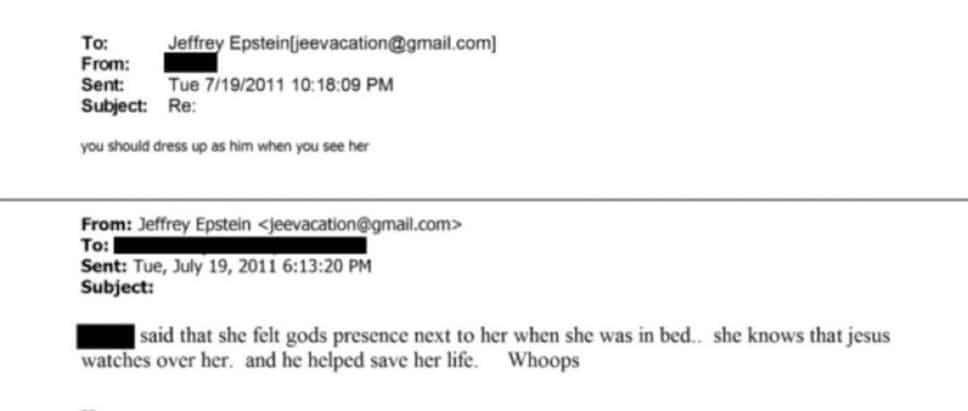

“(redacted) said that she felt gods presence next to her when she was in bed.. she knows that jesus watches over her. And he helped save her life. Whoops”

“You should dress up as him (Jesus) when you see her.”

The humour of rapists.

Men close to power. Men of power. Government and the wealthy class. Those in academia. The elites of society. Those who are powerful because millions of armed agents of government make them so.

Millions of ordinary people, citizens, who believe in the hierarchies of coercion and ensured through gatekeeping, believe in the church of government so long as their hands are fed more welfare, more jobs funded by coercive extraction, people who have to believe in the system. The ordinary and elites alike, who claim it can be investigated, again, reformed, again. Until the next gaggle of rapists, extortionists and murderers ascend.

The gods that sit in the thrones, never believed in it like the commoner does. The gods ascended because they understood it existed to be utilised, climbed. They are powerful because they rose above the ranks of the common person and rested on the shoulders of zealots and mercenaries, equally in the service of governments and institutions. Lower down, most know that failures are promoted, politics is rewarded above competency, honesty and dignity are shunned and suppressed, grift makes money more than honest work.

The gods see genocide as a land deal.

They see a young female, tethering on womanhood, the green youth of childhood as sweet nectar for their tastes, a commodity. A piece of flesh. Fuck chattel to be taken and discarded.

Yet, YOU have to believe in the system. You have to love government. You can not imagine a world without it. You need it. Funding comes from debt, taxation. Theft sold as a benevolent act of redistribution, rather than as a mechanism of control and punishment and a means to fun wars and schemes that suit a monopoly. Justifies it.

If only the gods were saints, then it would all work out. Just wait, vote again, reform some more, Tax! Regulate! Coerce harder! It will work this time, next time, Utopia is so close on the horizon, if only we crawl across the bones of the innocent, the sweat of the extorted and the blood of the raped and murdered. The laws and taxes will set us all free, in this Utopia!

The gods love you for it. They rule because of it. They are above it all, above you.

Dress as Jesus to fuck with her. As you fuck her. No idea how old she is. It’s unlikely she really wants to be there.

Does it matter to most? The reality most income is based on, the belief in it, is founded on coercion. The monopoly on violence is all a government is, It will murder, kidnap and beat any one who defies it. The trade off is that it provides order, stability, infrastructure. These are the things it provides to legitimise it’s existence. The social contract that no one signed, but was born to suffer. That’s the myth, the lie the gods need to reign.

Walk into the Canberra war memorial, see those foreign names, home grown martyrs to be revered as saints in a necropolis dedicated to violence. The blood sacrifice of glory, pride and nation. Over there. Killing then. Over there. The Unknown Soldier, a revered emblem, for all warriors, the tip of a nations pride, the empires blood sacrifice. What did he die for, nothing found in Washington, D.C. Nothing found on Epstein Island, he did for the things inside of his own mind, his own heart. A sacrifice in the end for them, over there, killing and dying, far from home, for them.

Manifest destiny? Breathing room? Gods Will? The White man’s burdern? The Nakba’s? Exterminate first, then land develop. Investment, jobs, gentrification above the dead. That’s how civilisations are built.

Freedoms erode. What can you do? What are you allowed to ingest into your own body? What can you view? What can you say? Are you a child, under the guise of an insecure and obsessed parent? Or, are you both a cog in the mechanism of a system that needs flesh to function, to tax, as armour should another government threaten, to validate it’s power. You are a subject beneath human gods. Flawed, immoral, ambitious and cruel. But subjects love their gods, they must, or the gods do not thrive.

Remember. Never forget. Such words were muttered as the death camps were opened up. The pale, skinny bodies of the survivors, days from death trembled with each breath, a piece of bread dangerous to their starving stomachs. That genocide was legal. Codified by a government and it’s allied governments. Lawyers and academics convened to rationalise the mass murder. It was a rationale built on exceptionalism, hatred. Policy. A job program. The killers were ordinary men, who believed in adventure and benefit to themselves. Gods made it possible, in that case a father figure of their fatherland, a great leader for the cult of race and nationhood.

Gulags and purges, mass starvation, mass murder, torture, rape all for the collective good. A scientific utopia devised from the minds of imperfect planners, tinkering with human life, academics and engineers deploying slaves for a planned economy of starvation and scarcity. Not for the gods, not for those who are more equal. Comrade leader, comrade gods each rose above and ascended even as the slavery and mass death was because of the proclamations of socialist egalitarianism.

And, should children be blown to pieces in the jungles of South East Asia, across a border it was an ‘illegal’ and ‘secret’ war. On the other side, it was a legal and open war. The innocent died beneath the bombs of the same air force. The illegal war meant as much as the legal one. Semantics to further rationalise the government. No president flew the bombers. Just men, eager to serve and kill. Thousands dead. The bombs fell regardless of legal or otherwise. It never mattered. Except for the murdered.

We can see children’s bodies falling to pieces as they are pulled from rubble, does it matter if it is in Gaza, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, Vietnam, Cambodia? To the grieving it always matters. To those, who lover government, there is nothing it does which can make them question it’s legitimacy. Religion has that power. It’s an infection of dependency which erodes morality and ensures loyalty, based on coercion and dependence. And reward.

What is more horrific than seeing a child burned to pieces, skin, bone, clothing melted into a disfigured mess, mouth frozen from screaming in pain during their final moments. To an American do they care if it was there government? To an Israeli, a Russian, a Briton? The policy makers made a decision and their uniformed warriors must act upon it. This is an understood reality. Its reasoned, rationalised. Academics give lectures on it. Legal documents are printed in the blood of such victims. Careers are made.

Is it any wonder that those who sit at the very top are capable of such sexual sadism? They would find a humours bravado to share it via a Gmail exchange? Most love them, or at lest reason with their power because of money, debt. It’s all debt now. Barely cash, certainly not sound. Meaningless now, based on belief, all our belief. Debt. To be paid back when? Never? Inflation, tomorrow? How? Debt, to buy things most don’t want or need. More landfill? To indulge into vices mostly there to numb and forget our days? Days spent in jobs most don’t love, for debt. To buy things to make the time lost and energy spent seem worth it? The older we get, the less horizons we have to climb towards, more are behind us. Time is more important, moments and yet, we now give that away for debt. That’s the magic of the gods.

Is it any wonder those who would benefit financially and as the status of elites above such a system, such nations that they would see an innocent girl, or woman with such dismissive disdain. To these gods of power it’s simply masturbation. To her, it’s her whole life.

The gods maybe incapable of changing how they think. Their subjects however, have no excuse.

Harry the Handbag’s House of Cards is About to Collapse

I loathe the British Royal family.

I loathe the Markle couple and Harry the Handbag even more.

Piers Morgan, love him or hate him, has done a standup and stunning expose on Meghan Markle’s financial skullduggery.

AMEX is going to blow this terrible fraud complex to smithereens.

The discovery process in this case in Calizuela is going to be quite revealing. loathe the British Royal family.

This will impact the Royals in the UK.

We: Records 36-40

Finish reading We

tommysalmons.com or @YearZeroPod on YouTube for video

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

The Kyle Anzalone Show: Sen. Schumer Touts Funding Genocide in Gaza, US Downs Iranian Drone Near Aircraft Carrier

A single clip can reveal the whole playbook. When a powerful senator calls military aid to Israel his “baby,” it says everything about priorities, leverage, and who pays the price. We pull the thread from that moment into the reality on the ground in Gaza, where a supposed ceasefire overlaps with daily killings and a systematic assault on healthcare. Detained physicians describe torture and maiming that read less like isolated abuses and more like a strategy to make Gaza unlivable. Pair that with efforts to block international medical work and you get collapse by design, not accident.

We also tackle the battlefield of narratives. For years, Gaza’s death tolls were dismissed as propaganda. Now, with the IDF effectively acknowledging those figures, the numbers stand—and so does the moral weight behind them. Meanwhile, legacy outlets still reach for soft phrasing, telling readers a ceasefire is being “tested” while children are buried. That language isn’t neutral; it shapes consent. The question is whether accuracy can survive the pressure to keep audiences comfortable.

Then we turn to Iran, where swagger and strategy collide. We dissect claims about a near-term nuclear bomb, point to inspections and intelligence, and examine how a cheap Iranian surveillance drone downed by an F-35 exposes a losing economic logic for endless escalation. With carriers near the Strait of Hormuz and merchant vessels as potential triggers, miscalculation could do what no speech intends: start a war. Add in maximalist U.S. demands—from missile limits to severing regional ties to dismantling civilian enrichment—and it’s clear why talks stall. These aren’t guardrails; they’re tripwires.

We close by pushing back on a convenient myth that Americans don’t care about the Epstein files. Crimes against children cut across ideology, and accountability still matters. We’re lining up a guest to go deeper and separate signal from noise as more documents surface. If you value frank analysis over spin—on Gaza, Iran, media narratives, and elite impunity—this conversation is for you.

If this resonated, subscribe, share with a friend who cares about foreign policy and accountability, and leave a review so more people can find the show. Your support keeps independent voices in the fight.

The Kyle Anzalone Show: Should We Believe Trump’s Truth Social Threats?

War planners love simple stories. Threaten, strike, and watch a “decisive” blow topple a hated regime. Today we peel back the layers on the rush toward Iran—what a decisive strike actually means, what the timelines look like from the Pentagon and Tel Aviv, and why air defenses are being surged across the Middle East. We connect the dots between public threats, carrier deployments, and leaked briefings that point to leadership-targeting plans paired with an oil blockade. Then we stress-test the assumptions: Iran’s missile and drone arsenal, Israel’s interceptor stockpiles, and the uncomfortable reality that U.S. bases from Iraq to Qatar sit squarely within range.

Diplomacy flickers at the edges with Turkish backchannels and whispered sit-downs, but Israeli “red lines” demanding zero enrichment and broader curbs on missiles and partners make agreement unlikely. We walk through the regional escalation ladder—Hezbollah in the north, Iraqi militias at home, the Houthis stretching air defenses from another axis—and explain how a “limited” strike becomes a map-wide conflict overnight. This isn’t an abstract war game; it’s a risk ledger for U.S. troops, Israeli civilians, and millions of people caught between missile arcs and sanction-induced scarcity.

Then we pivot to Cuba. The script feels eerily familiar: choke oil flows, squeeze the economy, court insiders, promise a clean transition. We unpack why decades of embargo failed to topple Havana, how sanctions can cement regimes by shifting blame, and why the most likely export of a forced collapse is a new migration wave to Florida, not a stable democracy. If the goal is real security, we argue for smarter off-ramps—credible diplomacy with Iran that sets achievable constraints, and calibrated engagement with Cuba that prioritizes humanitarian access and measured leverage.

If you care about avoiding a wider war and the blowback from brittle regime-change bets, this one’s for you. Subscribe, share with a friend who follows foreign policy, and leave a review with your take: what’s the off-ramp leaders keep missing?

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Capitalism Can’t Be Everything Its Foes Say It Is

“Nothing is more unpopular today than the free market economy, i.e., capitalism. Everything that is considered unsatisfactory in present-day conditions is charged to capitalism. The atheists make capitalism responsible for the survival of Christianity. But the papal encyclicals blame capitalism for the spread of irreligion and the sins of our contemporaries, and the Protestant churches and sects are no less vigorous in their indictment of capitalist greed. Friends of peace consider our wars as an offshoot of capitalist imperialism. But the adamant nationalist warmongers of Germany and Italy indicted capitalism for its “bourgeois” pacifism, contrary to human nature and to the inescapable laws of history. Sermonizers accuse capitalism of disrupting the family and fostering licentiousness. But the “progressives” blame capitalism for the preservation of allegedly outdated rules of sexual restraint. Almost all men agree that poverty is an outcome of capitalism. On the other hand many deplore the fact that capitalism, in catering lavishly to the wishes of people intent upon getting more amenities and a better living, promotes a crass materialism. These contradictory accusations of capitalism cancel one another. But the fact remains that there are few people left who would not condemn capitalism altogether.”

—Ludwig von Mises, Planned Chaos, 1947

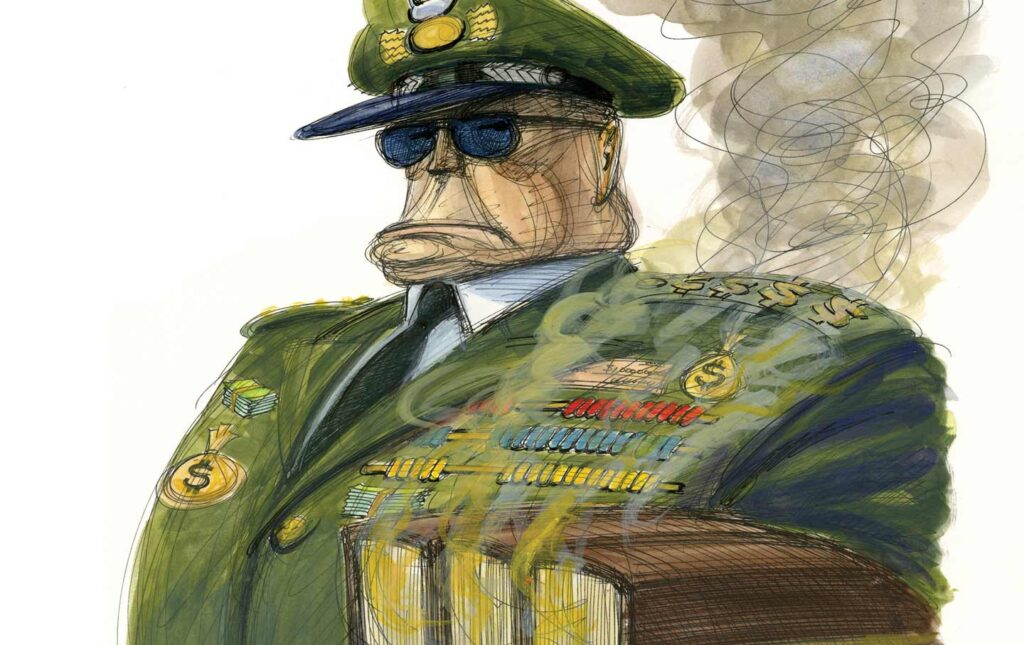

Rewarding Failure at the Galactic Level

One trillion dollars, the rest of the planet spends approx 2.4-2.7 trillion dollars, the Pentagon is not delivering much bang for the buck.

They even funded accounting errors to reward the poor performance of Pentagon program managers.

When combined with off DOD budget spending at Department of Energy north of 34 billion dollars and the associated intelligence spending, the budget for the notorious spendthrifts at the Department of War cavalcade of calamities is fast approaching a trillion debt-bucks.

Despite the $8 billion in added funds, because the Pentagon has submitted more than $50 billion in additional funding requests since its budget request was sent to Capitol Hill in June, the department will still be short some of the money it wants for FY26.

Those additional requests include $26.5 billion to mitigate funding discrepancies between its FY26 request and the reconciliation bill — essentially a laundry list of accounting errors that resulted in shortfalls to key programs like the Virginia-class submarine. While some of those shortfalls were addressed by the $8 billion increase, not all are covered.

The late requests also included an additional $2.3 billion in “emergent requirements” and a whopping $28.8 billion sum for multiyear munitions procurement contracts, which largely went unfunded.

You could double the DoW budget tomorrow and they would still ask for more, fail audits at the retail & wholesale level and still pile on creating the most awesome 20th century peer fighting force not fit for purpose for peer combat in the 21st century.

Read the rest:

https://breakingdefense.com/2026/02/house-passes-839b-defense-spending-bill-teeing-up-end-to-government-shutdown/