“You were still reading that book when I walked by three hours ago. It must be a good one.” Sitting outside the cafe, I looked up to see a man strolling by on the sidewalk. I gave him an affirmative smile, and turned my book so he could see the cover.

All afternoon on that chilly mid-December day my mind was fully embedded in The Iron Dice of Battle, the first major biography of Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston in nearly six decades.

I chose this compact book (only 184 pages sans endnotes) as my holiday read to indulge my boyhood love of the American Civil War. And with the recent, disgraceful removal of the postwar Reconciliation monument from Arlington National Cemetary, remembering the war and the people who fought it feels like a civic duty.

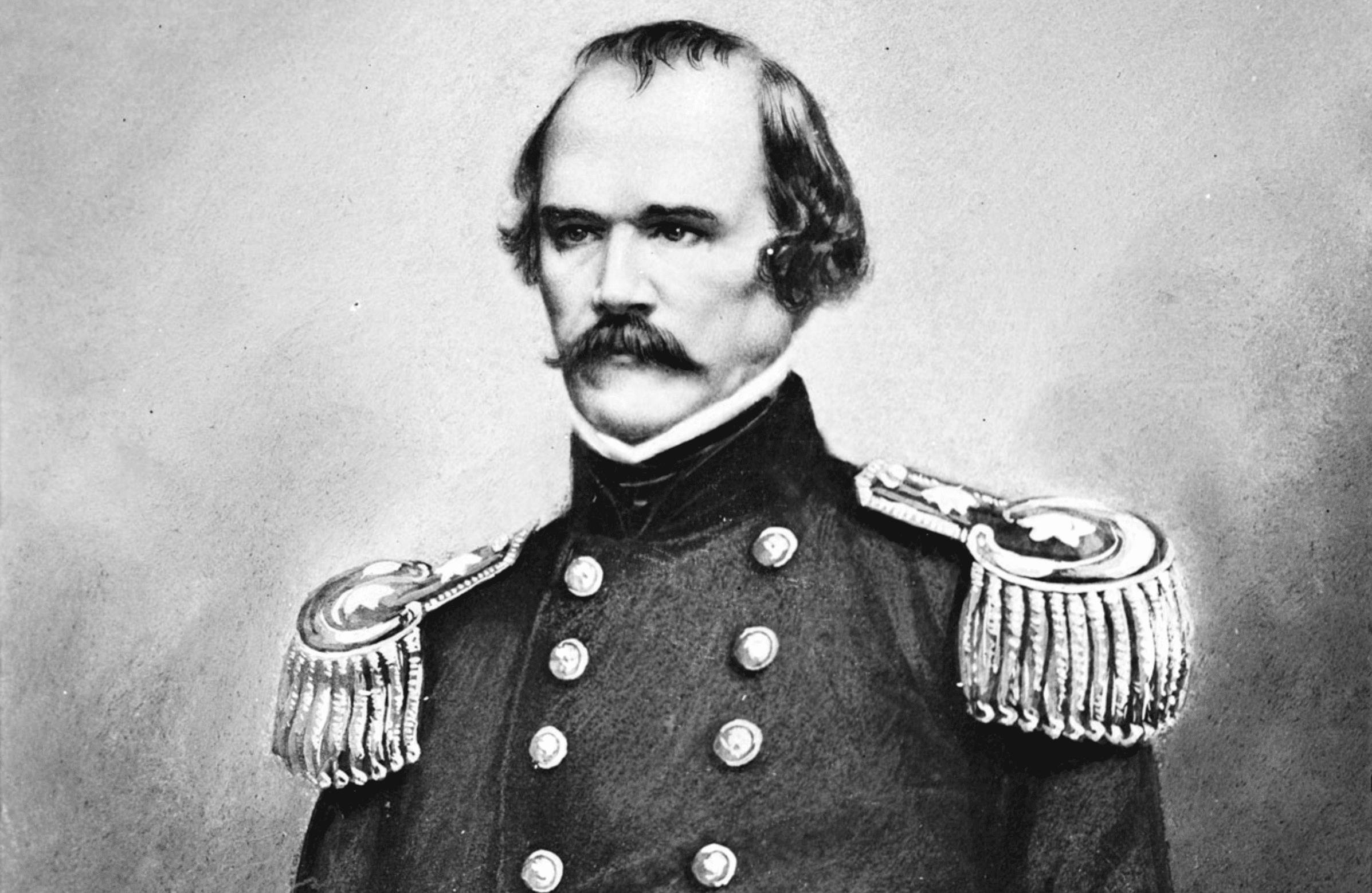

When I picked up this biography, I knew significantly less about Johnston’s life than I did other southern icons. I knew he had a prestigious reputation as a soldier, that he was beloved in his adopted state of Texas, that Confederate President Jefferson Davis looked at him with particular awe, and of course, his brave but fatal charge at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862.

Every time I flipped a page I was waiting to discover a momentous event that demonstrated Johnston’s immense capability, something to give weight to his posthumous legend. For over 150 years it’s been common parlance among Civil War aficionados that if Johnston had lived, he’d have the won the war for the south. But the more I read, the more I became perplexed about that expectation.

In brief;

- Johnston graduated 8th in his class at West Point, and was certainly an above average student.

- He was technically in the 1832 Black Hawk War, but never saw combat.

- He cast his lot with the Republic of Texas after the revolution was finished, and despite moving from head of their army to be secretary of war, he never led a military campaign.

- During the Mexican-American War, the only combat Johnston saw was at Monterrey, before he left the army on orders from his wife. During the battle he had three horses shot from under him while trying to stabilize one of the lines.

- As an army paymaster, it took him years to figure out one of his slaves was stealing thousands of dollars from the government.

- He commanded the army’s expedition to Utah to quell the Mormons, who surrendered without a fight.

- In addition, his attempt to live as a gentleman planter never prospered and he died in immense debt.

Johnston was unquestionably brave, even to the point of stupidity; he accepted duels he knew he’d lose (being a bad shot). But steadiness under fire doesn’t equate to capable battlefield command. It’s not so much that his prewar record lacks competency, but it’s barren of moments which to me would signal untapped greatness.

Halfway through the book, I discussed with a friend the positive impression that Albert Sidney Johnston left on the people around him—over six feet tall, deliberate and methodical, patient, calm and easygoing—despite his career achievements being ambiguous at best. “He was just tall and everyone assumed he was good at his job because he was tall,” my friend mused. I believe there’s a big grain of truth in that.

One thing this book did inadvertantly change my mind about: despite his infamous reputation as such, I no longer believe Braxton Bragg was the worst soldier of the American Civil War. As inept and grouchy as Bragg proved to be as a general, I’m firmly convinced that crown should rest on the feeble head of Leonidas Polk, whose inadequacy from the moment the war began crosses the threshold from useless into obstructive.

And that’s what most weighed down Johnston’s command of the Army of the Tennessee. Not only was he charged with maintaining a 600 mile defensive line filled with rivers against three enemy armies, but he was surrounded by mediocrates and poltical appointees with no military skill or background in uniform.

Was Johnston too trusting of his subordinates, and too deferential to the judgement of lower commands? Absolutely. But in the fall of 1861, when persons and units are being shuffled into their starting positions, how can a leader not default into automatic trust until lived experience proves otherwise? In December Johnston ordered Polk to send reinforcements from Columbus, Kentucky to Fort Donelson, Tennessee. Unfortunately, he didn’t follow up afterwards to ensure his orders were followed. Then in January, he was surprised to learn that Polk never sent the reinforcements, and the fort was still weakly defended. Can you blame him for being surprised? If Johnston had lived to command into 1863 and beyond, it’s possible that he would have witnessed enough shortcomings to sack inferiors like Polk and Gideon Pillow. But to do so before April 1862? I believe that’s demanding too much foresight from any general.

The Iron Dice of Battle contains little anecdotes and snippets that are gems for any reader. The one that most made my jaw drop was when Johnston was stationed at Sackett’s Harbor, New York in the 1820s:

“Johnston had little to do except read, and his boredom almost go him into trouble when, during artillery practice over the frozen lake, he purposefully fired in the general vicinity of some recreationists on the ice. The shot landed far too close for comfort, and for a few seconds Johnston was afraid he had hurt or even killed some of the skaters. Fortunately, they were fine and beat a hasty retreat, though not without sending shouts and gestures his way.”

This is the best example of giving into invasive thoughts that I’ve ever read. It’s like driving and wondering what would happen if you spun the wheel and drove onto the sidewalk…but then actually doing it.

Author Timothy Smith presents his thesis through the lens of Johnston, a slowly thinking chess player in his personal life, forced into a high-stakes game of poker for control of the Mississippi River Valley. It’s a game that Johnston wasn’t equipped to win, but predisposed to gamble big. It’s a great metaphor, but one that Smith feels compelled to repeat ad infinitum throughout the book.

The focus of The Iron Dice of Battle is on the war, not Johnston’s early life (less than a quarter of the book), which is a welcomed decision. Smith’s comprehensive presentation of Confederate military movements in the west from spring 1861 to spring 1862 is easily digestable and supremely informative.

By the time we reach the penultimate chapter on Shiloh, Johnston’s better qualities as a commander begin to emerge. He organized his army into his preferred corps; he formulated a strategic plan to immediately engage the Union armies piecemeal (risky, but admittedly the best course available); contrary to his natural meekness, he resolutely committed to his plan once put into action; and on the battlefield, he recognized where his personal leadership was most needed, and willingly sacrificed his life to take the field.

Would Johnston’s survival have reset the western theater and aided the Confederate cause to victory? Smith is restrained in this counterfactual, and evenhanded in his judgement of Johnston’s decisions, even challenging previous historiography. The Iron Dice of Battle is a worthy and enlightening read to cement your own opinion.

In the whole book, I found the best insight belonged to Jeremy Gilmer, the senior engineer on Johnston’s staff. Writing to his wife as the Army of Tennessee consolidated and prepared for battle, Gilmer assessed, “We have here now Genls. A. S. Johnston and Beauregard—Maj. Genls. Bragg and Polk and Hardee—and Brigadier Genls. too numerous to name. Among them all, I fear there is not a Napoleon.”