As American consumers and businesses face the looming possibility of additional tariffs under a second Trump administration, it is worth revisiting the incisive critique of protectionism put forth by economist Murray Rothbard in his book Power and Market. Rothbard’s analysis exposes protectionism not as a tool for national prosperity but as a mechanism for enriching politically connected interests at the expense of the general population. With policymakers entertaining yet more trade restrictions, his arguments remain as relevant as ever.

Protectionism, in its essence, involves the use of any combination of subsidies, tariffs, quotas, and other trade barriers to insulate domestic industries from foreign competition. Advocates argue that such measures safeguard jobs, promote national security, and support fledgling industries. These claims often resonate with voters, particularly in a climate of economic uncertainty. Yet, as Rothbard demonstrates, protectionism is fundamentally flawed in both theory and practice.

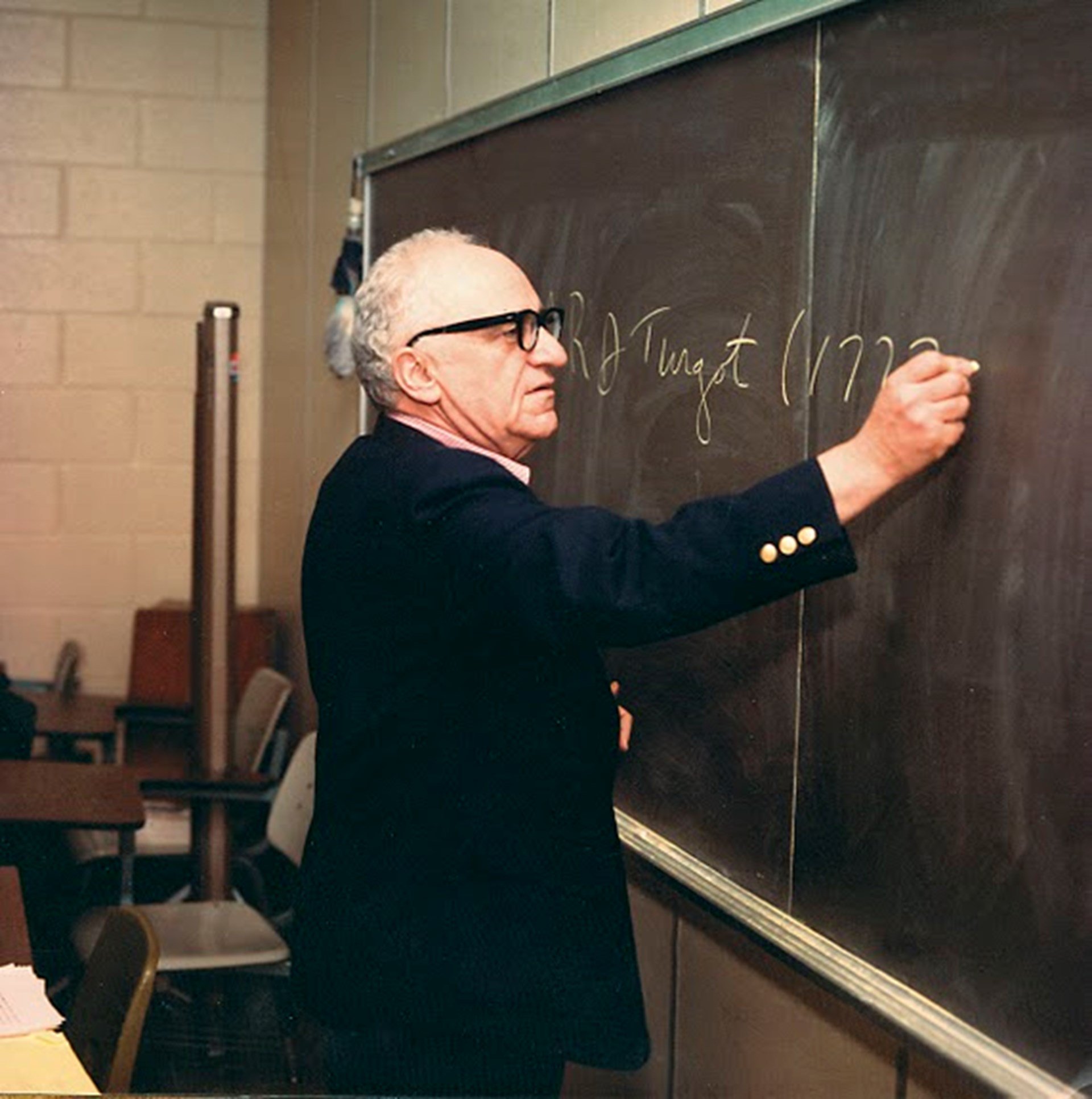

At the heart of Rothbard’s critique lies the principle of free trade, which he defends as a cornerstone of economic prosperity. Drawing upon the insights of the classical economists, he emphasized the mutual benefits of trade and the principle of comparative advantage, and correctly identified that protectionism fatally undermines these benefits, impoverishing society as a whole while propping up inefficient industries.

In “Chapter Three: Triangular Intervention,” Rothbard highlights how tariffs distort the market by artificially raising the prices of imported goods. While this might seem to benefit domestic producers, it imposes significant costs on consumers, who must pay higher prices for both imported and domestically produced goods. Rothbard’s analysis reveals that these costs often outweigh any potential gains, making society poorer on net.

For example, a tariff on steel might protect American steelworkers, but it also raises the cost of steel for all other industries that rely on it, such as automobile and construction companies. This ripple effect leads to higher prices across the economy, reducing overall productivity and efficiency.

Protectionism is, as Rothbard always incisively identified, never about the public good. Instead, it reflects the influence of special interest groups seeking to shield themselves from competition. Tariffs and quotas are tools of economic privilege, transferring wealth from the general population to politically connected industries.

This dynamic can be seen in modern tariff policies, where lobbyists for industries like steel, agriculture, high technology, or auto manufacturing push for protectionist measures under the guise of patriotism or economic security. The beneficiaries are concentrated and vocal, while the costs are dispersed among millions of consumers, making resistance politically challenging.

One of the most common and fallacious arguments for protectionism is that it preserves domestic jobs. Rothbard dismantles this notion by pointing out that while trade barriers may save jobs in protected industries, they destroy jobs elsewhere in the economy by artificially raising the price of labor, in effect punishing more efficient businesses with higher costs of labor for the sake of the favored businesses or industries. Further, higher consumer prices mean less disposable income, leading to reduced spending in other sectors. Moreover, industries that rely on imported materials face higher costs, forcing them to cut back production or lay off workers.

Trade, by contrast, reallocates resources to their most productive uses, creating wealth and enabling job growth in competitive industries. Rothbard underscores that the free market, not government intervention, is best equipped to direct labor and capital efficiently.

Beyond its economic failings, Rothbard critiques protectionism on moral grounds. Trade barriers are a form of coercion, restricting individuals’ freedom to exchange goods and services across borders. As such, they violate the principle of voluntary exchange, which is fundamental to a free society.

Lastly, regarding the remarkably weak yet eternally regurgitated arguments about national security, apart from serving as a convenient excuse for economically destructive policies in the name of serving connected interests, in a globalized economy trade fosters interdependence, which can actually enhance security by creating mutual incentives for peace and cooperation.

Rothbard’s warnings about protectionism resonate strongly in the context of President Donald Trump’s trade policies. During his first term, tariffs were imposed on a range of goods, from Chinese electronics to Canadian steel, under the banner of “America First.” The consequences were predictable: higher prices for consumers, disruptions to global supply chains, retaliatory tariffs from trading partners, and a bailout for negatively affected but politically important constituencies.

While these policies were marketed as a way to revitalize American manufacturing, they often had the opposite effect. Many businesses faced increased costs, forcing them to scale back operations or relocate production overseas. Meanwhile, consumers bore the brunt of higher prices, effectively paying a hidden tax to fund protectionist policies—to say nothing of taxpayers, who paid an average of $100,000 per job “created” by government policies.

The prospect of additional tariffs once again looms large. Trump’s rhetoric continues to emphasize economic nationalism, resonating with voters who feel left behind by globalization. Yet, as Rothbard reminds us, the costs of protectionism are borne not by foreign nations but by American consumers and businesses.

As the United States grapples with the possibility of renewed protectionism, Rothbard’s critique serves as a powerful reminder of its dangers. Tariffs may appeal to populist sentiment, but their economic and moral costs are too great to ignore. Policymakers would do well to heed Rothbard’s call for free trade, rejecting the siren song of protectionism in favor of policies that promote genuine prosperity.