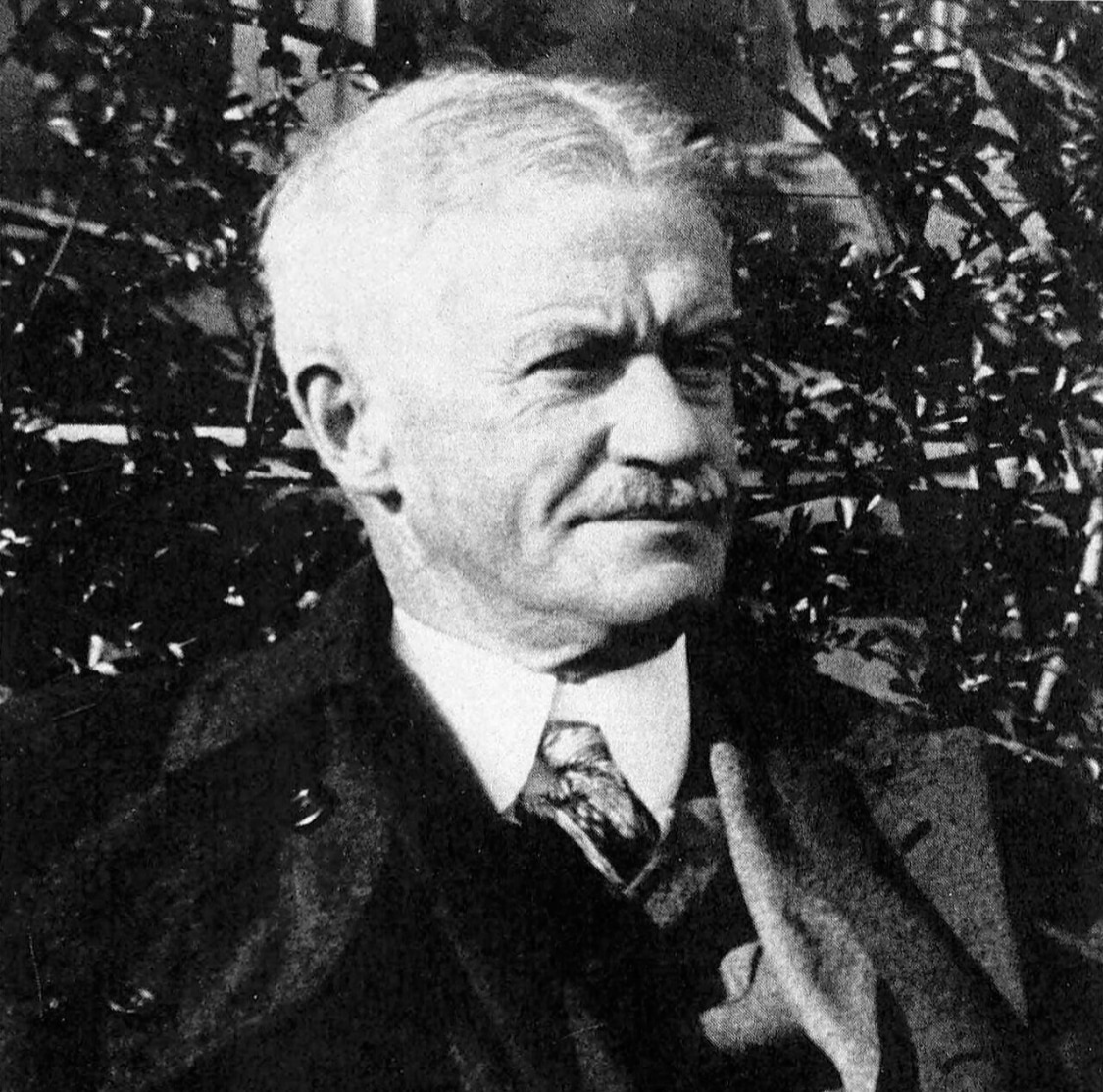

Albert Jay Nock’s life spanned the transformation of the United States from the laissez‑faire America of the late nineteenth century to the managerial state of the New Deal. Born on October 13, 1870 in Scranton, Pennsylvania, Nock studied Greek and Latin in the classical curriculum at St. Stephen’s College. He was ordained as an Episcopal priest in 1897, but church life proved too confining; within a few years he left the pulpit to write for American Magazine and to edit The Nation. In 1920 he and bookseller B. W. Huebsch launched The Freeman, a weekly that presented essays by radicals and conservatives alike and championed individual liberty. Nock wrote a large share of each issue, and contemporaries considered it the best‑written journal in America. Today he is remembered as one of the earliest Americans to describe himself as a libertarian and as an influence on later conservatives, including William F. Buckley Jr., who credited Nock’s writings with shaping his own thinking.

Nock’s political ideas developed out of the reform movements he encountered in New York. Early on he embraced Henry George’s single‑tax proposal, denouncing the privileges that accompany land monopoly. He co-founded The Freeman with Francis Neilson to promote free trade and individual liberty, and although the journal never achieved a large circulation, it earned a reputation for its fearless criticism. Nock’s skepticism toward politics deepened when he read the sociologist Franz Oppenheimer, who distinguished between the “economic means” of satisfying wants through production and exchange and the “political means” of acquiring wealth produced by others. For Nock this contrast illuminated the difference between government, understood as a voluntary association that secures natural rights and leaves citizens free, and state, which institutionalizes the political means and lives off confiscation. The distinction became the organizing principle of his later work.

During the First World War, Nock stood apart from the patriotic consensus. He dismissed the conflict as a “scramble for loot” and predicted that the Versailles settlement would sow the seeds of further tyranny. By 1932 he warned that Germany was drifting toward “Napoleonic absolutism,” and he argued that whether a system calls itself Bolshevism, fascism, or the New Deal, it subordinates the individual to the collective. Defending the right of every person to pursue happiness so long as no one else is harmed, he emphasized voluntarism and personal responsibility. Having rejected the progressive label once it became synonymous with centralization, he turned his fire on President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. In May 1934, he wrote that federal centralization had produced an “organized pauperism,” with agencies distributing funds according to political convenience rather than genuine relief. He warned that taxing citizens based on ability to pay would cultivate dependency and expand the client class. Such positions left him almost alone in resisting both war and welfare during an era of widespread enthusiasm for them.

Nock’s critique of the modern state extended to public schooling. Early in his career he admired progressive education, but by the 1920s he was attacking the movement inspired by John Dewey. In lectures later published as The Theory of Education in the United States, he argued that schools had abandoned classical learning for vocational training. Educational egalitarianism, he warned, conflates equal rights with equal intellect: rights are equal under law, but capacities are unequal. While praising parents’ hopes for their children, he noted that the system was “gauged to the run‑of‑mind American rather than to the picked American,” designed for the lowest intellectual denominator rather than cultivating excellence. Mass schooling produces docile workers and voters but not the disciplined minds required for liberty. Genuine education, he insisted, should be reserved for those capable of it and should cultivate intellect and character rather than prepare pupils for jobs. This elitism, while controversial, sprang from his conviction that social progress depends on the growth of a small number of individuals rather than on mass programs.

Nock’s skepticism about politics led him to refocus on culture and personal development. In his June 1936 Atlantic Monthly essay “Isaiah’s Job,” he retold the biblical story of the prophet Isaiah. God instructs Isaiah to warn Judah of impending destruction and then adds that no one will listen. Isaiah asks why he should speak, and God responds that there is a “Remnant” that must hear his message. Nock used the story to argue that serious writers and teachers should address themselves not to the masses but to the Remnant—a small minority capable of understanding and preserving the principles of a free civilization. The Remnant cannot be identified beforehand and cannot be enlarged by propaganda; the teacher must simply tell the truth and trust that prepared minds will find the message. When the masses have carried everything down to destruction, the Remnant will rebuild. This emphasis on quality over quantity resonated with later libertarians and conservatives. Frank Chodorov revived The Freeman in 1937 and used it to promote non‑intervention and free enterprise. William F. Buckley Jr. adopted the Remnant metaphor to argue that a principled minority can stem the tide of statism. Nock’s appeal to the few over the many offered an alternative to progressive faith in mass politics and suggests why he embraced the label “superfluous man.”

In his most systematic political work, Our Enemy, the State, published in 1935, Nock traced the historical origins of political power. Drawing on Oppenheimer, he argued that no primitive state in history began by consent; instead, all arose through conquest and confiscation. The state’s essential function, he wrote, is the “continuing economic exploitation of one class by another,” and its administrators are barely distinguishable from a professional criminal class. Voluntary government, by contrast, exists to protect natural rights and leave citizens to their own pursuits. Once the political means are available, those with ambition will inevitably seize them to secure tariffs, subsidies, and privileges. Because these incentives persist, attempts to reform the state fail; each new movement simply redirects exploitation rather than abolishes it. Although the book attracted little attention in its own time, its argument that political authority originates in violence would become a cornerstone of later libertarian critiques of government.

Nock’s 1943 autobiography, Memoirs of a Superfluous Man, offers a quieter, more personal argument for liberty. He begins by calling himself a superfluous man, but the memoir records his formative experiences and demonstrates how a society can function without extensive government. He recalls growing up in a Michigan town where police were nearly absent and life was “singularly free”; the only officials were the sheriff and his deputy. “We were so little conscious of arbitrary restraint that we hardly knew government existed.” Their community, he suggests, could have served as an advertisement for Thomas Jefferson’s conviction that American virtues thrive best in the absence of government. Rather than rely on political schemes, he argues, improvement comes from cultivating personal discipline and good character. When reformers proposed new social systems, he would ask what sort of people would administer them and conclude that there are none good enough. The memoir’s calm style attracted readers during the turmoil of wartime, and it inspired future conservatives, including Buckley.

Although Nock considered himself a radical rather than a party loyalist, his writings shaped both libertarianism and the Old Right. Historian Walter Grinder summarizes his legacy as a philosophy of self‑responsibility and inviolable individualism. Publisher Henry Regnery credited him with contributing to modern conservatism. His concept of the political means influenced Austrian economists; Ludwig von Mises similarly argued that state coercion and economic freedom cannot coexist. By criticizing business interests as well as socialists for seeking special favors, Nock distinguished himself from apologists for either camp. Many of his warnings about centralization and privilege were later vindicated, and his Remnant idea encouraged intellectuals to focus on cultivating a principled minority. In the postwar period, his works provided inspiration for Frank Chodorov, the Foundation for Economic Education, and William Buckley’s fusion of libertarian and conservative ideas. A pro‑New Deal editor of The New Republic even conceded that Nock was among the soundest commentators on political history, while conservative scholar Russell Kirk praised his erudition and style.

Nock’s radical individualism emerged from a distinctive combination of classical learning, personal experience, and skepticism about modern politics. As a priest‑turned‑editor he promoted free speech and non‑intervention through The Freeman; as a theorist he drew on Henry George and Franz Oppenheimer to distinguish between voluntary government and exploitative state. In Our Enemy, the State he argued that political authority is rooted in conquest and that reforms merely shift the beneficiaries of exploitation. In Memoirs of a Superfluous Man he depicted a community thriving without heavy government and insisted that improvement is a matter of character rather than policy. His essay “Isaiah’s Job” urged truth‑tellers to address the few who can preserve civilization. By insisting that the state is “purely anti‑social” and that renewal comes from a Remnant, Nock anticipated later critiques of centralization. On his 155th birthday, revisiting his works reminds us that liberty and responsibility remain inseparable and that the warnings of this superfluous man still merit attention.