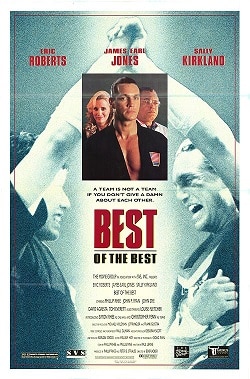

“A team from the United States is going to compete against Korea in a Tae Kwon Do tournament. The team consists of fighters from all over the country – can they overcome their rivalry and work together to win?”

The 1980s gave us a wave of action movies like no other decade. The martial arts genre was especially popular, filled with montages, mullets, listenable soundtracks, and individuals overcoming the odds. They kicked ass. The 1989 film Best of the Best was a celebration of all of those things. A simple plot about the U.S. karate team forming, training, and then travelling to Korea to take on their almost superhuman rivals.

The five members of the U.S. team all have character. It is a film that celebrates individuals coming together as a team, rugged individuals who may not see eye to eye or even initially get along. It is an age old trope, the arc of heroes and cooperation. Individuals with agency, uniting willingly for a common goal that also widens into interpersonal overlaps. As any community does or group organically knows, it does not require coercion or planning. It is teamwork and mutual aid.

It is said that “There is No ‘I’ in team” but team is made up of four individual letters that come together to make a word. And for the five men and their coaches of the U.S. Karate Team, that word becomes apparent in the end.

They’re led by James L. Jones as head coach Frank Couzo, a man with an eye not just for talent but other traits that make for a good fighter. His assistant coaches are Tom Everett’s Peterson, a statistician and data man along with Sally Kirkland as Wade who helps the fighters with their mindset. Wade specializes on focus and meditation, internal attributes that are less than appealing to some of the athletes. Wade is the soft internal, maternal contrast to the hard and physical approach of Couzo.

Veteran Karate fighter Alex Grady, played by Eric Roberts, is a blue collar worker from Detroit, a single father who lives with his mother. The injured Karateka has responsibilities and comes from a hard working background, the chance to compete again is his last shot at glory for himself and his son. Though further injury can harm his abilities to work and provide for what is left of his family, it’s a calling and a risk that he undertakes. This perspective and his experience gives him a maturity and wisdom.

The most talented fighter on the team, Phillip Rhee’s Tommy Lee, runs a Tae Kwon Do school. He is the caricature of the perfect martial arts instructor. Humble, disciplined and in prime physical shape, beneath the need for competition lays the pain of his past. As a boy he watched his older brother die in a tournament; his opponent on the Korean team is the man responsible for the death. Played by his real life brother, Simon Rhee, Dae Han is an eye patch wearing menace of a warrior. For Tommy it is about revenge and facing the fear of his past.

The teams trouble maker Travis is played by Chris Penn. Rude, racist, and beneath his cowboy hat believes he is every lady’s man. Out of shape but all fighter, Travis is not interested in cardio or Coach Wade’s meditations, just the fight.

John Dye is Virgil, a peaceful Buddhist hippy type and Sonny, every Italian-American stereotype, is played by David Agresta. Early on the team must come together in a bar fight that was in part instigated by Travis. It’s an action scene but also an opportunity to show each man’s character as an individual fighter and their willingness to come together in a crisis.

The common thread that unites these individuals is important: victory. It is a relatable objective that can motivate one to sacrifice and work hard. After scenes of butting heads, training injuries, a son nearly dying in an accident and revelations of Tommy’s brother’s death the team pulls together in time for the tournament. The adversity and differences strengthens them. At any stage they can quit, walk away and leave the others to face the determined Koreans. Instead they help one another, stand together and support the other and fight for themselves, their team, and those who are watching.

As a contrast the Korean team is rigidly traditional, the product of a culture that does not embrace individual difference but only the collective good. The harmony of nation and community must come first. The team members are products of a national training regime that is gripped in modern methods and ancient rituals designed to harden the body and strip the human from the man. The film starts with an army of Tae Kwon Do uniform clad black belts performing a form (kata). They are indistinct; conformity is crucial, each is in harmony with the other, martial Confucianism on display. The Korean team is selected from this group and each trains the same; though different men their individual identity is only defined by their martial arts skills and some very physical distinctions. They are the contrast to the uniqueness of the American team. The film does not show these men as human beings, they are the foreign other. Koreans rivals, unlike the unique individuals of the American team.

After montages from both camps and American team character moments, we have the tournament. It is exciting and majestic in its choreography though gruelling for the film’s competitors. Travis must break bricks using the internal methods that he learned from Coach Wade. The old shoulder injury returns for Alex who has to fight one armed after painfully having it “popped” back into place and Tommy must face his brother’s killer. After an epic display of kicks, the fight is close. Dae Han is slightly ahead on points and just as the clock runs down Tommy has his opponent all but defeated, standing and unable to defend himself. Ready to execute a deathblow to Dae Han, while chambering his powerful spinning back kick Tommy is primed for victory. From the sidelines his team mates and coach yell to him “Tommy, No!” “Coach, he is going to kill him,” Alex warns. Instead Tommy shows mercy and he loses the fight. Dae Han, his brother’s killer, lives. The team loses on points.

Through competitive adversity, dignity, and courage the American team earns the respect of the Korean crowd and their rivals. Team USA did not win the sports match, though they won far more immaterially. The film, like many action movies of the era, was steeped with morality lessons and arcs for each of the characters. It was not made to win Oscars only to entertain and inspire. Dae Han and Tommy reveal their humanity, acknowledging the loss of his brother and the regret that such a death had caused. Both men had demons and pain, one as a sibling with survivor’s guilt and the other as a competitor who took the life of another. Tommy gains a brother in his opponent.

There was a time when not just American but much of Western culture celebrated the individual, the hero or rogue who did what was needed when the chips were down; the band of different players that unite willingly to meet adversity with cooperation and team work. There is no need to coerce and to homogenize the individual into one reluctant or even mindless unit. They are unique and distinct with their own ambition and experiences. It was almost universally understood and embraced. These fictional characters were unique as individuals and not written as agents or avatars representing a political community to depict contemporary ideological patisanship. Good characters are evergreen, as is individualism and team work.

Before the age of the superhero where magical powers and otherworldly abilities defined those who did good, there was the hero who trained hard or worked for it. Those of ability and character who in the case of Best of the Best, a team of individuals who cooperated, learned from one another and improved self and each other. These are humbling and enriching experiences that are not indoctrinated, only learned by example and experience. In both fiction and life it seems such understood traits are now disregarded and even disdained by some. The individualism that is seemingly welcomed is one that is more avatar or preference rather than of deed and character.

While it is a genre film, a VHS classic, it is a treasure for individualism. It does not shy away from the Rocky IV patriotism. The enemy is not the Soviet communists but they are from the far east and possess a culture that is different and distant to that of the United States. The five American karate fighters are representing their nation. They do so not as an indistinct corporate package but as who they are. Uniquely fighting for themselves and their team, the bar stool voyeur to family members who can relate to them. Everymen doing extraordinary deeds, with hard work, risk, and preparation but above all individual character. Five different fighters through the course of the film forming into the “U.S. National Karate TEAM.” No coercion, just voluntary desire and understanding. In the end that made them all winners as a team and as individuals.