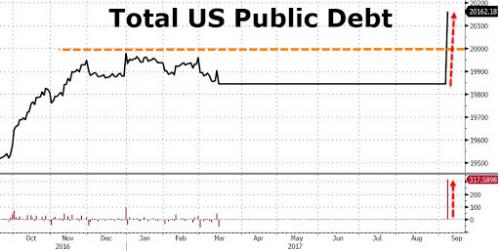

Last Friday, on September 8, President Trump signed into law a new 3-month suspension on the debt ceiling. On that same day, the US Treasury decided to celebrate the event by borrowing an additional $318 billion, increasing the national debt to over $20 trillion for the first time in US history.

Or at least, that’s how it appears in the official government financial figures.

In fact, the situation is probably even worse. On paper, the US’s official indebtedness grew by $318 billion Friday. In reality, the US government had already incurred this debt weeks ago.

Welcome to the strange world of government accounting, where the common sense definitions of terms are distorted beyond all recognition.

Creative Definitions

The particular term being distorted in this case is debt. The intuitive meaning of a debt ceiling would be to place an upper limit on all debt. Accountants might make a practical case that contingent liabilities (for instance, those related to lawsuits) and unfunded liabilities (like those related to pensions) should be excluded from a debt ceiling because of the uncertainty involved in estimating them. But at a minimum, most people would agree that debt should include all obligations that definitively exist, and must be paid to someone or some entity.

Thus, when people hear the idea of a debt ceiling, they might assume that it places a limit on the total amount of money that the government can borrow. They would be wrong.

The debt ceiling, such as it is, actually only applies to a subset of the total national debt. It excludes the massive unfunded liabilities related to Social Security and Medicare, which might be expected. But it also excludes bona fide obligations to actual entities.

This is why the debt ceiling crisis only reared its head in September of this year, even though the US national debt has actually been right at the debt ceiling limit since March 16, 2017, when the previous debt ceiling suspension expired. As of March 15, the debt ceiling was reinstated at $19,808,772 million, and the official government debt has been treading water just below that number ever since.

How did the government do this?

Well, it wasn’t by maintaining a balanced budget since that time. And although the Treasury did pay down its cash balance considerably to try to cover the deficits since March, they didn’t have nearly enough to make it all the way to September.

Creative Accounting

To keep the government running without breaching the debt ceiling, the government had to rely on what the Treasury Department calls “extraordinary measures”. This ominous phrase includes things like borrowing hundreds of billions of dollars from the government workers’ pension fund in a way that doesn’t count towards the debt ceiling.

Because this is government, they don’t explain what they are doing with that kind of straightforward language of course. (They call this “investment suspension”.) But that is the substance of what is taking place.

If these extraordinary measures are exhausted and the debt ceiling isn’t lifted in time, the Treasury admits that the government would have to limit payments to pensioners–because the pension money would have already been borrowed and spent. But once the debt ceiling is lifted, then the extraordinary measures are no longer necessary. At this point, the government is required to make the government’s pension fund whole again, paying it back with interest. Sure sounds like debt to me.

These types of arrangements are the real reason we saw government debt spike up massively on the first day that the debt ceiling was lifted. The government was recovering from its extraordinary measures. Essentially, we were witnessing the government shift liabilities from one pocket that doesn’t count toward the official debt ceiling to another pocket that does count toward the official debt ceiling. Because in Washington, that’s what passes for fiscal discipline.

Implications

Based on this discussion, it appears that the debt ceiling is a perfect microcosm of today’s politics. In order to appear fiscally responsible to voters, Congress passes a law establishing a “debt ceiling” at a particular level. But Congress also passes language that helps ensure the debt ceiling does not really cover all debt, weakening the constraint in subtle but important ways. Then, when even this more generous limit is reached, Congress votes to increase it anyway–reminding us all that the debt ceiling would be more appropriately called a debt milestone.

Perhaps more importantly, this is another example of the double-standard that often exists for government. If the CFO of a private company used creative accounting to hide massive liabilities from their shareholders or lenders, they would be rightly prosecuted and sued for fraud. But when the federal government wants to do what amounts to the same thing, Congress passes a law to make it legal.