It’s an economic article of faith among almost every school of economic thought that central banks raising interest rates curtails economic growth and lowering interest rates stimulates short-run economic growth.

The problem with this assertion by nearly every economist is that the data backs up the inverse proposition.

Lower real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates are statistically associated with slower short-term and long-term economic growth as well as short-term higher prices for housing.

Low interest rates are also the regular and ongoing policy of the Federal Reserve Bank.

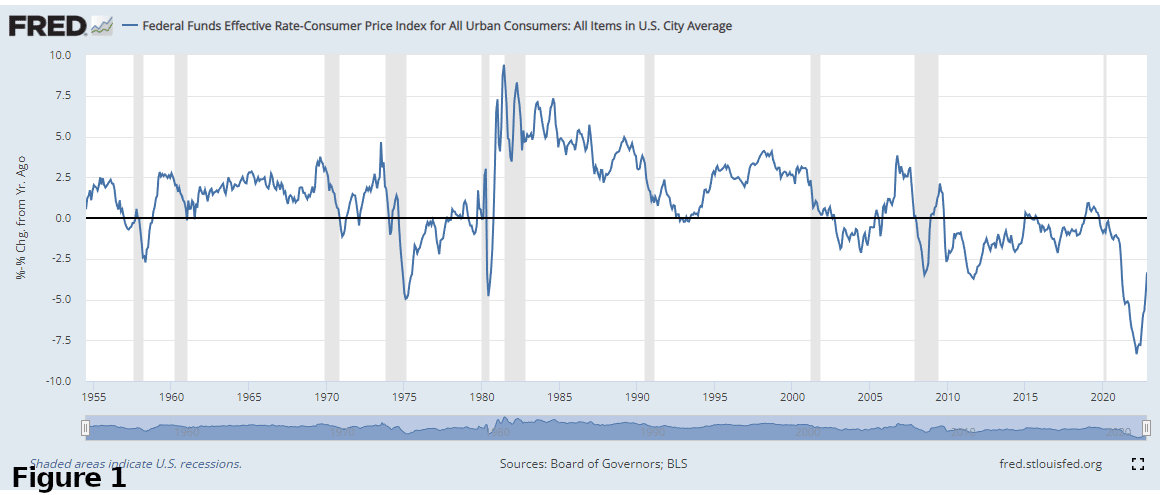

Both legislators and economists are currently fretting about “too restrictive” an interest rate policy that could throw the American economy into recession. The Federal Reserve recently raised its Federal Funds Rate—the discount rate to banks—to a nominal rate of 4.5 percent. But the real interest rate (inflation-adjusted by the Consumer Price Index) remains deeply negative and near historic lows (Figure 1).

A look at historical data on interest rates and economic growth

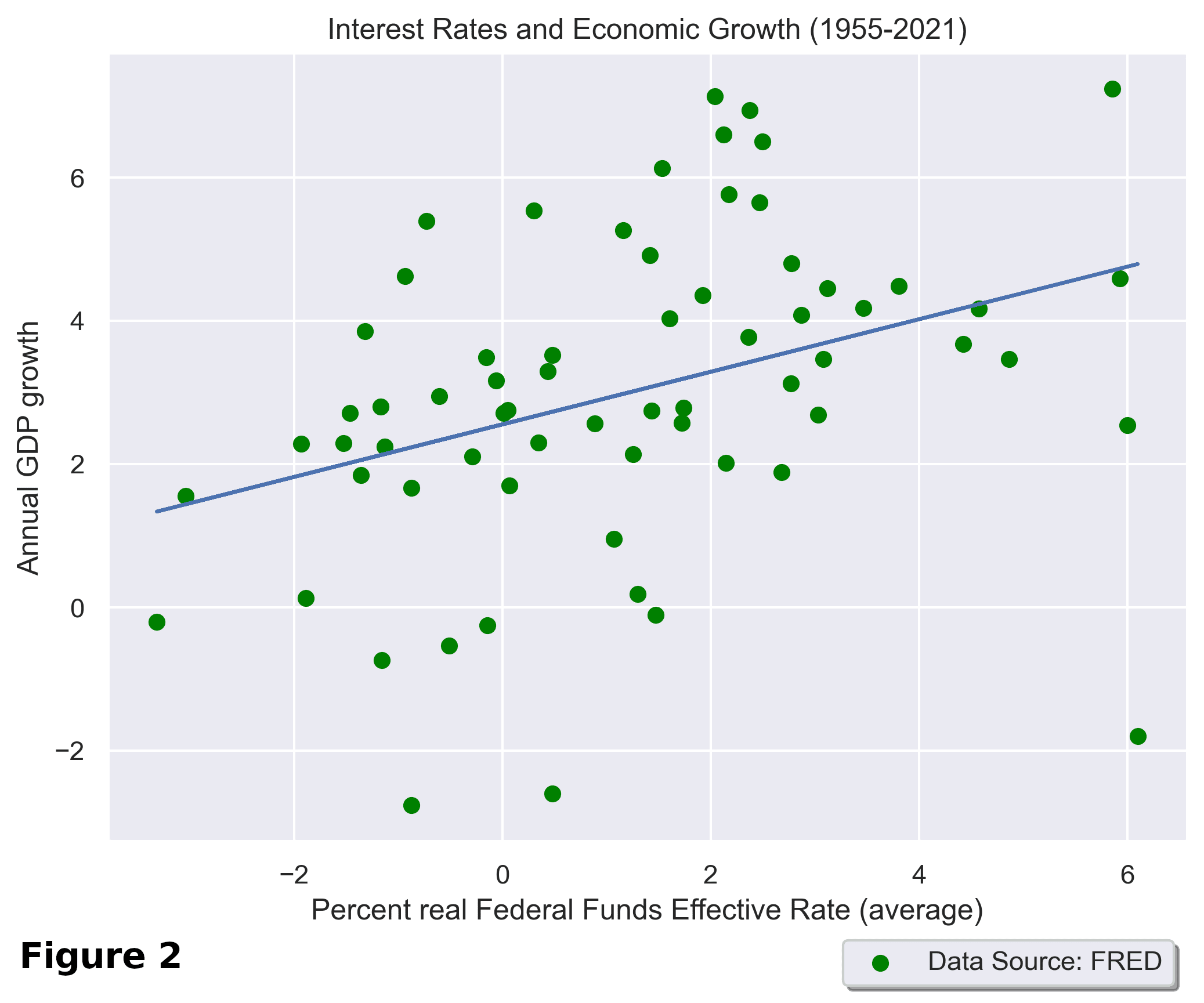

Real (CPI-adjusted) Federal Funds Rates and annual GDP growth can be extracted from FRED, the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank’s online database, from which the relationship between the two factors can be measured. And the results are: Lower real interest rates are statistically associated with slower GDP growth (and higher interest rates with faster economic growth), according to an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analyzing the variance at the 98% confidence level (for the nerds: p-value = 0.02).

Graphically, this would be represented by Figure 2, with each year since 1955 representing a green dot on the scattergraph.

Keynesian school economists would argue that low interest rates are associated with slower economic growth because central banks reduce interest rates when the economy is soft. In essence, they argue the cause and effect are reversed and that high interest rates statistically “cause” economic growth only because central banks raise interest rates when the economy is already strong. Likewise, because suppressing interest rates stimulates, that’s why interest rates are lowered during a recession already underway. The argument is that sub-market interest rates prevent recessions being even worse than they already are.

And it is true that most of the time central banks lower interest rates during recessions.

But that has only been the history of the past thirty years. In the early 1980s, interest rates were raised during the stagflation era, which ended with a pretty severe recession. Most free market enthusiasts, the monetarists and Austrians, have in the past argued the reason America saw a severe recession in 1980-81, the strongest recovery since that time, and the end of high inflation was because interest rates were raised sharply during that time period (more on the last point about inflation below).

So the question then becomes this: are higher growth rates statistically associated with higher economic growth only because the Fed increases interest rates during times when the economy is already good and cuts it when the economy is in rough shape?

That seems unlikely from longer-term historical data. The above results are buttressed by research showing that U.S. growth over a longer period of time (1836-2021) was stronger during periods before interest rates could be suppressed by the Federal Reserve Bank. The period of higher interest rates before the 1970s show that economic growth was significantly stronger than since 1970.

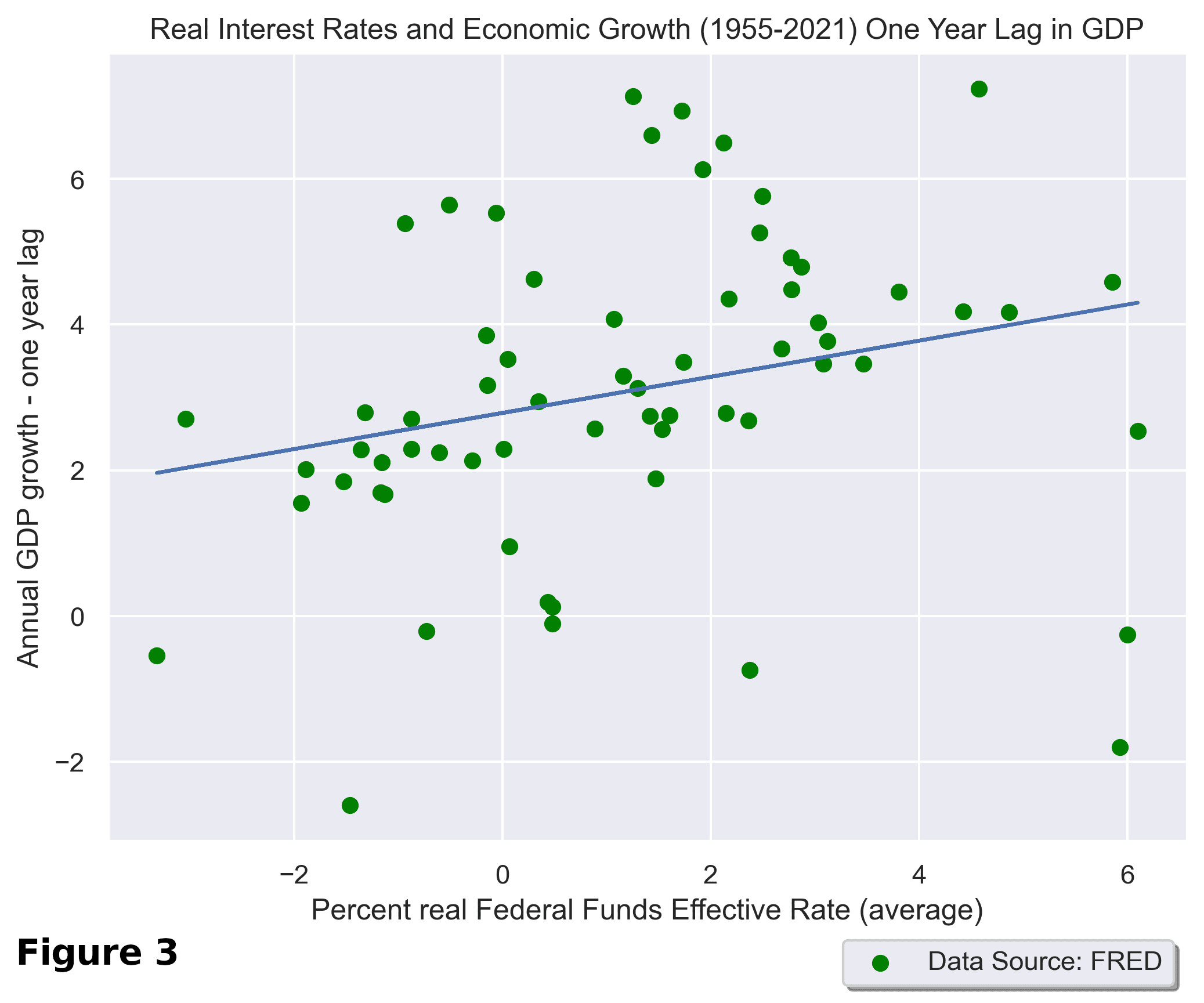

Nevertheless, the thesis that lower interest rates induce a “stimulus” which bring a recovery and higher interest rates curtail an overheated economy can be measured against historical empirical data. This can be done by measuring economic growth the year after interest rates were high or low to verify whether lowering interest rates has a stimulative or suppressive effect upon economic growth.

The result is basically the same (Figure 3), with higher interest rates leading to higher economic growth the following year, statistically significant to the 95% confidence level.

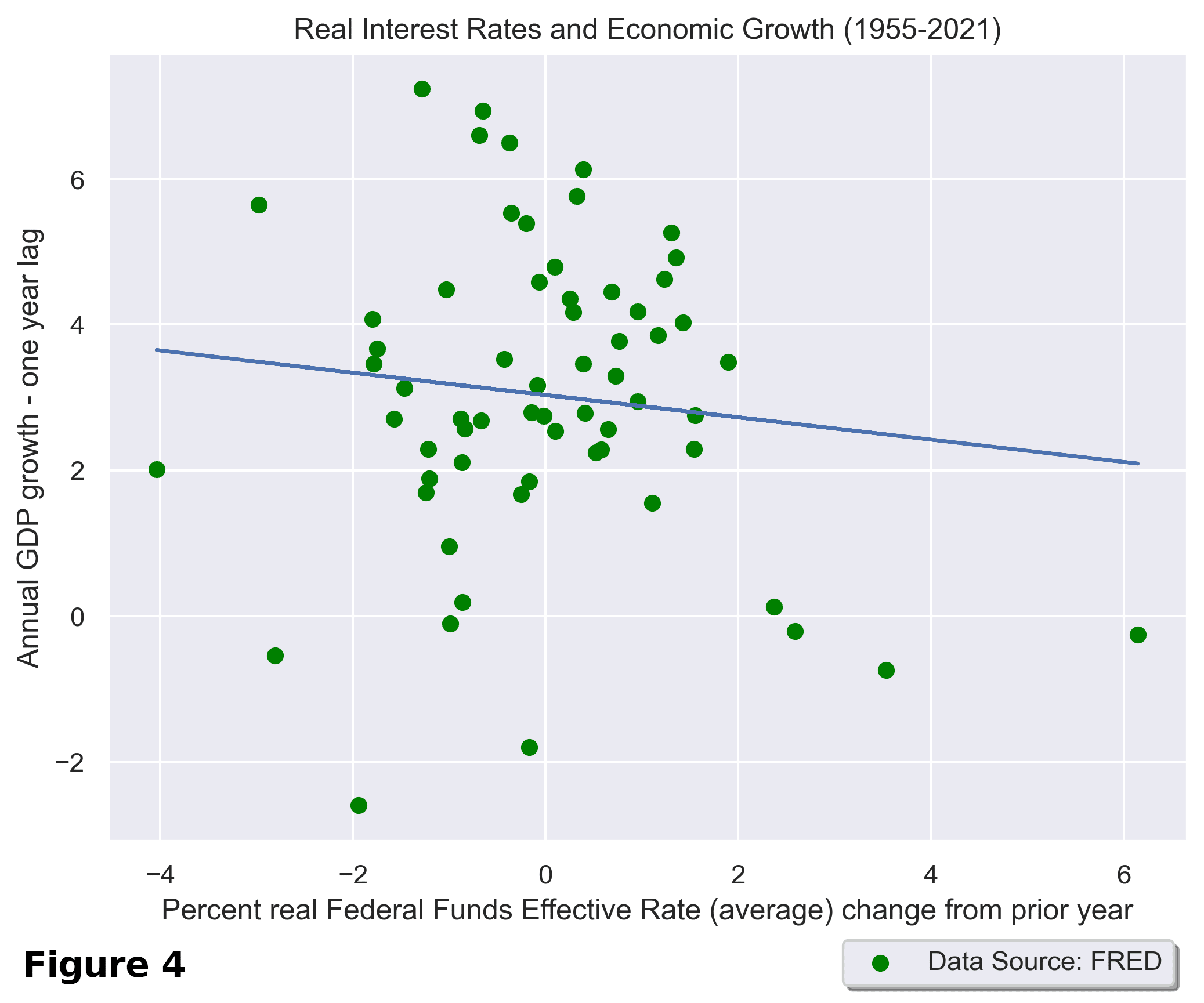

It’s possible one might argue it’s not the real (CPI-adjusted) interest rate that induces stimulus but the magnitude of the change in interest rates that creates the economic pull-back. In other words, the argument could be made that lowering real interest rates from four percent to two percent is stimulative but raising interest rates from minus-one percent to plus-two percent is restrictive, relatively speaking.

This can also be tested by the data, by measuring the annual rate of change in the Federal Funds Effective Rate against GDP growth. While the below scattergraph chart (Figure 4) shows a negative coefficient, the results of an OLS (Ordinary Linear Squares) regression show that the results were not statistically significant.

At best, the thesis that lowering interest rates stimulates economic growth in the short term lacks empirical evidence.

So how is everyone wrong?

The intuition behind the empirical evidence that lowering the interest rate doesn’t increase economic growth can be found in studying one of the industries most impacted by interest rate changes: the housing market.

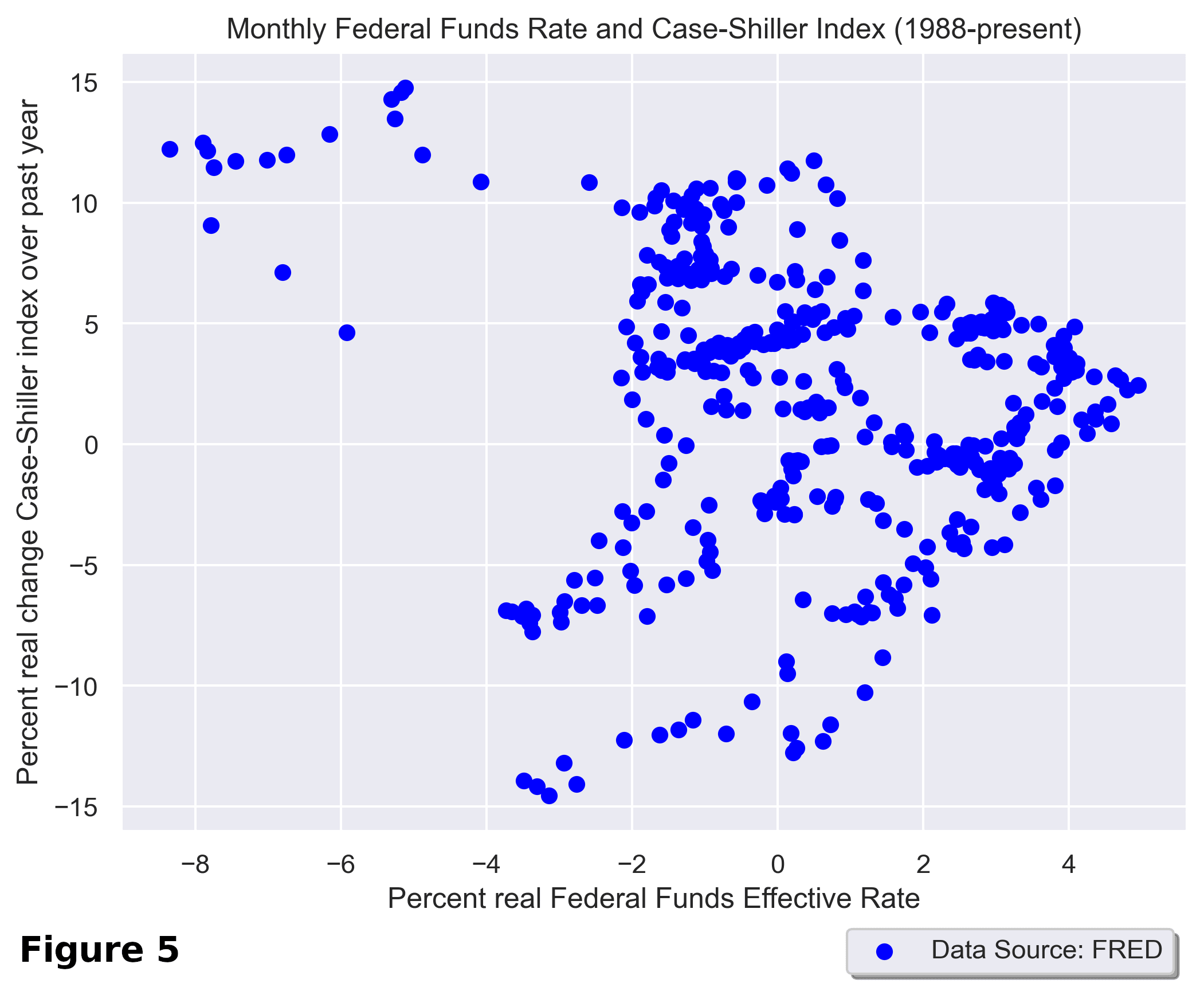

A graph of the Case-Schiller index of median home prices against the Federal Funds Effective Rate across the United States shows the following:

The first thing one notices from the above graph (Figure 5) is that the data looks like an arrowhead. The higher the interest rate, the lower the variance, and the lower the interest rate, the wider the variance. In essence, the chart shows that lower interest rates don’t on-net increase housing prices, but they do cause much more chaos in the market.

Also note that all of the top-left quadrant is 2021-22, when real (CPI-adjusted) interest rates have been at record lows.

Looking at the above graph, it’s obvious how suppressing interest rates would make the housing market more unpredictable and precipitate something like the 2008-09 banking crisis.

But the Case-Shiller graph is also perhaps a useful analogy for the economy as a whole, and an intuition on why lowering interest rates doesn’t stimulate overall economic growth, even in the short-term.

In the case of the housing market, lower interest rates do tend to increase prices and valuations initially, but they also drag purchasing power and value away from the other sectors of the market not based primarily on credit, lowering the proportionate nominal value of those other sectors. Eventually, the housing market crashes, bringing value back to the other sectors of the market.

Interest rates are the price of money, and when the wrong market signal (a price higher or lower than the organic market) is forced upon an economy, the end result is almost always an economic loss. The bad signal to market forces to over-invest in housing represents a net-loss to the economy, leading to slower economic growth over the long-term. And in the case of the housing boom it’s an economic loss driven not by the spurred investment of the credit-based real estate market, but by the relative monetary starvation of non-credit-based markets.

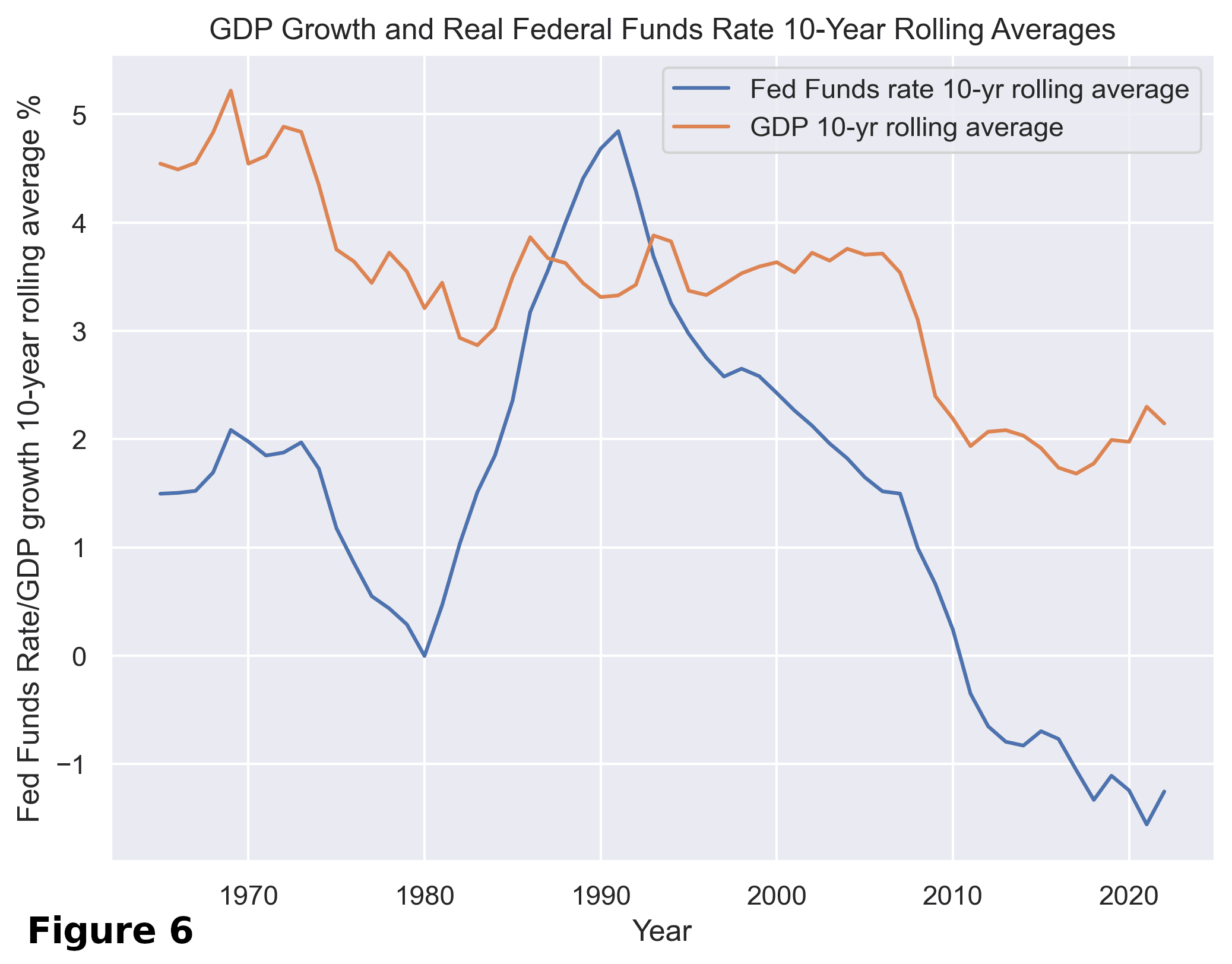

And that net-loss explains (in part) the slower economic growth rate since interest rates started being highly suppressed by the Federal Reserve Bank in the year 2000. This intuition is backed by statistical correlation between 10-year rolling averages for the Effective Federal Funds Rate and GDP growth (Figure 6), a strong positive statistical correlation using the OLS method between growth and interest rates to the 99.9% confidence level.

Slower growth rates also tend to hurt the working poor and middle classes the most, as they generally don’t have assets to leverage gains in an economy. For working people, the only point of leverage they have is the point of sale of their labor at the time the new wealth is created. Diminishing this increase in wealth creation diminishes their bargaining power.

Free market economists have been sold a narrative, based upon then-Fed Chairman Paul Volcker’s raising of interest rates in the early 1980s, that this increase was necessary to fight inflation but it was higher interest rates that first caused the recession.

In fact, neither assertion is backed by empirical evidence. When real and nominal Federal Funds Effective Rates are measured against the CPI, they show that higher interest rates have no demonstrable statistically significant impact in curbing inflation, either in the current year or in CPI numbers the following year. Indeed, nominal Federal Funds rates show a strong positive correlation with the CPI, likely as a result of the Federal Reserve Bank choosing to raise nominal interest rates sharply during times of high inflation. Likewise, lower interest rates don’t push up the CPI either.

These numbers help explain both why the massive expansion of credit beginning in 2001 did not push up the Consumer Price Index and why the CPI did increase over the past two years as (at least nominal) interest rates have increased.

An increase in the amount of credit via means of the Federal Reserve Bank suppressing the discount interest rate (and other QE policies) pushes up the prices of selected assets like real estate, and (to a lesser extent) stocks, as these are often purchased with credit.

But an increase in the amount of liquid money (M1 or M2) eventually increases the price of commodities, as these are generally purchased with cash or checking accounts. For example, real estate is almost always purchased on credit, while food is almost always purchased with currency or near currency.

This explains why the CPI hardly budged 2001-2020 while real estate and stocks saw initial record increases and subsequent wide variations, while the recent increase in the CPI for commodities like food is related to the massive increase in new currency created by the Federal Reserve Bank since 2020.

The Federal Reserve Bank’s efforts to manipulate the interest rates by lowering them to fight recessions and raising them to fight price inflation do not have any results-based empirical evidence. That’s probably a tough assertion for many to accept after decades of propaganda. But the empirical data is evidence in favor of letting the market decide interest rates without fear of recession or an increase in the CPI, a market that would almost certainly raise them higher than the current near-historic lows if left unmolested by the Federal Reserve Bank.