I saw reported somewhere that 50% of books purchased are never actually read—at least not to the end. I have also noticed in my own reading of contemporary books that many of them start out strong but eventually fall off a cliff. My best guess is that the authors of such works managed to secure generous advances for agreeing to deliver a finished manuscript according to a strict deadline. With a looming due date, authors hoping to obtain future contracts may be more concerned with retaining good relationships with their agent and publisher than with taking the time necessary to produce a satisfying finish to a book filled with promise, at least judging by the query letter and opening chapter used to woo acquisitions editors. Many writers also know, however, deep down inside, that the best books, the ones which stand the test of time, rather than achieving momentary popularity as a result of dizzying marketing blitz campaigns, are not constrained by deadlines. They are finished when they are finished and not one moment before.

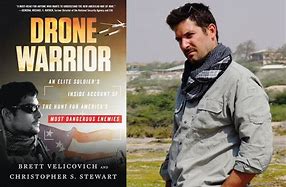

Why, you may be wondering, is any of this relevant to Drone Warrior: An Elite Soldier’s Inside Account of the Hunt for America’s Most Dangerous Enemies, by Brett Velicovich? Primarily because the glowing endorsements of this book by military professionals and administrators of the drone program such as Michael Hayden (who serves on the boards of multiple kill-for-profit companies) suggest that they may never have finished reading the book. Skimming through the opening chapters may well give the impression that Drone Warrior offers a defense of remote-control killing. The epilogue, however, tells a quite different story.

I wanted to read Drone Warrior, despite its endorsement by targeted killing profiteers, because I think that it is important to attempt to understand how anyone (sane) could possibly believe that hunting human beings is a worthy profession, and how, in particular, well-adjusted drone operators, sensors and analysts, those who do not suffer from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), regard what they do. In many interviews over the past several years, we have heard the heart-wrenching testimony of drone program whistleblowers, and we know from a variety of sources that many operators and sensors do not renew their contracts, even when offered enticing bonuses to continue on. But this is not only (as the US military would have us believe) because the job involves long, eye-glazing hours of staring at a screen in a dark room.

Films such as Good Kill (2014) and National Bird (2016) have offered some excellent anti-recruitment advice to would-be enlistees. Eye in the Sky (2015), in contrast, attempts to defend the practice of hunting down and killing even nationals abroad by the British government (though capital punishment is prohibited under UK and EU law), and that film may have succeeded in persuading some young people to believe that contract killing can be a noble profession—or at least that it is not obviously murder.

“Insurgents were like having a house infested with rats; the more of them you killed, it seemed, the more they bred.” (Predator, p. 252)

Martin cultivated a palpable disdain for his targets, even while acknowledging that many of them were “angry poor people” incensed by the invasion and occupation of Iraq by the US military in 2003. At the same time, in diaphanous attempts to rationalize what he was doing, Martin compares himself to the US troops who traveled to France to save its people from the German occupation in the 1940s. In fact, a more nuanced consideration of the two cases (beyond “USA! USA!”) reveals the role of the US invaders of Iraq to be much closer to that of the Germans than to the US troops during World War II.

Drone Warrior opens provocatively, with the author, a drone program analyst, explaining that this memoir has been approved by the US military, which censored some parts prior to publication. To my mind, the most surprising omission is the section where Velicovich briefly describes his encounter with “Mr. White” (not his real name), a recruiter who persuades him to go behind “a black door”. Velicovich proceeds, with an air of mystery, to explain that he is not permitted by those vetting his work to reveal how it was that he was converted to the hunter/killer life. His inability to explain what happened to him cannot help but evoke memories of Jason Bourne’s induction into the class of assassins who kill on command—no questions asked.

Whatever may have happened (if it wasn’t illegal, why in the world should it be classified?), Velicovich accepted the invitation, and from there set off for life in “The Box,” where, fueled by a steady diet of Rip It® energy drinks and Frosted Flakes, he spent long days spying on potential terrorist suspects from afar. He developed “pattern of life” folders on the men he surveilled and, ultimately, gave “his” Delta operators the green light when “a bad guy” had been confirmed as such (found and fixed) by him and his drones. That 90% of his targets were, as he claims, captured rather than killed stretches credulity, to put it mildly, given the near absence of detainees taken prisoner under President Barack Obama during the later years when Velicovich plied this trade.

While working for President George W. Bush, Velicovich, like Matthew J. Martin, never seemed fully to grasp that the ever-intensifying insurgency in Iraq was a direct result of none other than the US troops’ presence, and especially their increasingly brutal raids, interrogations, and executions of persons, some of whom proved to be undeniably innocent—not even being identifiable as military-age males. Perhaps it was a combination of sleep deprivation and excessive consumption of energy drinks and sugar-coated cereal which induced in Velicovich an inability to grasp that many of the able-bodied Iraqi males deemed “fair game” by the US invaders wanted nothing more than for them to leave their land.

Disturbingly, as the occupation of Iraq was winding down, Velicovich and his buddies received an order from on high to eliminate as many people on their hit lists as swiftly as they could—a murderous form of “scorched earth”. This “green light” from (dare I say?) Corporate headquarters inspired something of a killing spree as the hunter-warriors attempted to wipe out “the enemy” while they still had the chance. Even while acknowledging that the military-age men being killed were community members—sons, husbands, fathers and brothers—Velicovich leapt at the chance to eliminate them, having convinced himself that they were “bad guys”.

What I find most interesting about this memoir is that Velicovich openly acknowledges the effect that living as a hunter of human beings had upon his mind, his body, his relationships and, ultimately, his life. He became obsessed with his targets, and when he returned to the United States after a prolonged period in “The Box” abroad, working grueling hours, suffering bouts of insomnia and sleep deprivation, and losing 40 lbs as a result, his girlfriend frankly informed him that he had changed:

“Your eyes, they don’t look the same,” she said. … “They’re like stones. They just sit there.” (Drone Warrior, p. 151)

Velicovich freely owns that as a result of his profession he stopped experiencing emotions at the news of anyone’s death, and his relationship with his girlfriend ultimately fell apart. While working an office job stateside, the analyst wanted to feel the same rush he got from hunting his targets, and he attempted to mimic it through online gambling, but with no success. Velicovich returned to “the battlefield,” this time in Somalia, having found life as a civilian too humdrum. One is certainly reminded here of Staff Sergeant William James, the lead protagonist (played by Jeremy Renner) of Kathryn Bigelow’s 2008 film, The Hurt Locker.

In Somalia, Velicovich shared his “expertise” with locals in a very different context and one in which he himself faced significant danger, given the reigning instability in that land and what he perhaps rightly portrays as an environment ripe for a “Black Hawk Down” redux. His new girlfriend is distressed that he should prefer the hunter-killer life over their relationship, and eventually he renounces his position, though he insists in this memoir that, if given the choice, he would do it all over again.

The epilogue of Drone Warrior is not at all the paean to remote-control killing which one might have expected from a book lauded as “the definitive account of our nation’s capacity and capability for war in the modern age.” In fact, it reads more like a PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) infomercial. Velicovich, who became obsessed with his targets and returned to “the life” after having abandoned it once, finally decided to take a very different path. Inspired by animal rights activists in Kenya, he left the military and embarked on an entirely new career, establishing a company in which his prowess as a drone analyst can be used to stop poachers from destroying endangered species such as elephants and rhinos. Through this new venture, Velicovich appears to have achieved a kind of redemption, but in his own eyes, he is and always was one of the “good guys.” It surely takes some mental gymnastics to believe that elephants and rhinos have more significant rights to life than do human beings in a land under illegal occupation. (What did go on behind that black door?)

To be honest, I am somewhat surprised that this memoir was published, for the undeniable conclusion of the work—to anyone who makes it through the all-important epilogue—is that serving as a hunter-killer of human beings is not a tenable path to The Good Life. While deployed, and throughout his memoir, Velicovich takes great pains to convince himself (as did Matthew J. Martin in Predator) that he is a worthy warrior doing what must be done. The bereft survivors of the raids and drone strikes carried out in Iraq on the basis of his analyses would no doubt beg to differ—particularly in cases where the “bad guy” in question was attempting only to defend his territory from the invaders.

At one point, Velicovich details his benevolent use of drones to help a doctor whose wife had been kidnapped by ISI (the Islamic State in Iraq—before it expanded into Syria). But he declines to offer details on any of the cases where “mistakes were made” and never consciously faces up to the cold, hard, and grisly truth: that had he and his comrades not been in Iraq, then ISI would never have morphed into what became its murderous and virulent form. Following the call of Al Qaeda, Muslim men did indeed flock to Iraq for the opportunity to kill the heathen invaders, but all that the US soldiers needed to do to prevent most of the locals from attempting to kill them was to leave.

The fact that Velicovich needed to find a new profession in order to rehydrate his human capacity to feel emotion strikes me as just as important as the testimony of apostate drone program personnel suffering from PTSD that this frenzy to maximize lethality and to make body counts the be-all and end-all of US foreign policy was a horrendous mistake from the very beginning. As drone killing spreads around the globe, with petty despots following the lead of the self-styled “beacon on the hill,” defining their political enemies as “evil” before summarily executing them with drone-delivered missiles, the normalization of assassination by the sole military superpower must be recognized for what it is: a tragedy for humankind and a hideous assault on not only democracy and the rule of law but also simple decency.