Archival institutions are not known to be pioneers of technological innovation. They are preoccupied with the past, after all. That is why censors still often black out classified information physically, with a marker, a piece of paper or whatnot.

The Israeli State Archives, on the other hand, have apparently been experimenting with virtual censorship tools. In the minutes of a cabinet meeting of Israel’s provisional government during its “War of Independence,” released following requests of the Akevot Institute, digital blackouts were included to cover the more problematic statements made by the Zionist leaders present. As the Israeli newspaper Haaretz recently found out, however, these comments could be unveiled with a simple click. Woops! (Perhaps due to a similar technical error, I was able to access the paywalled Haaretz article once. Fortunately, the details can be found at Middle East Eye, too.)

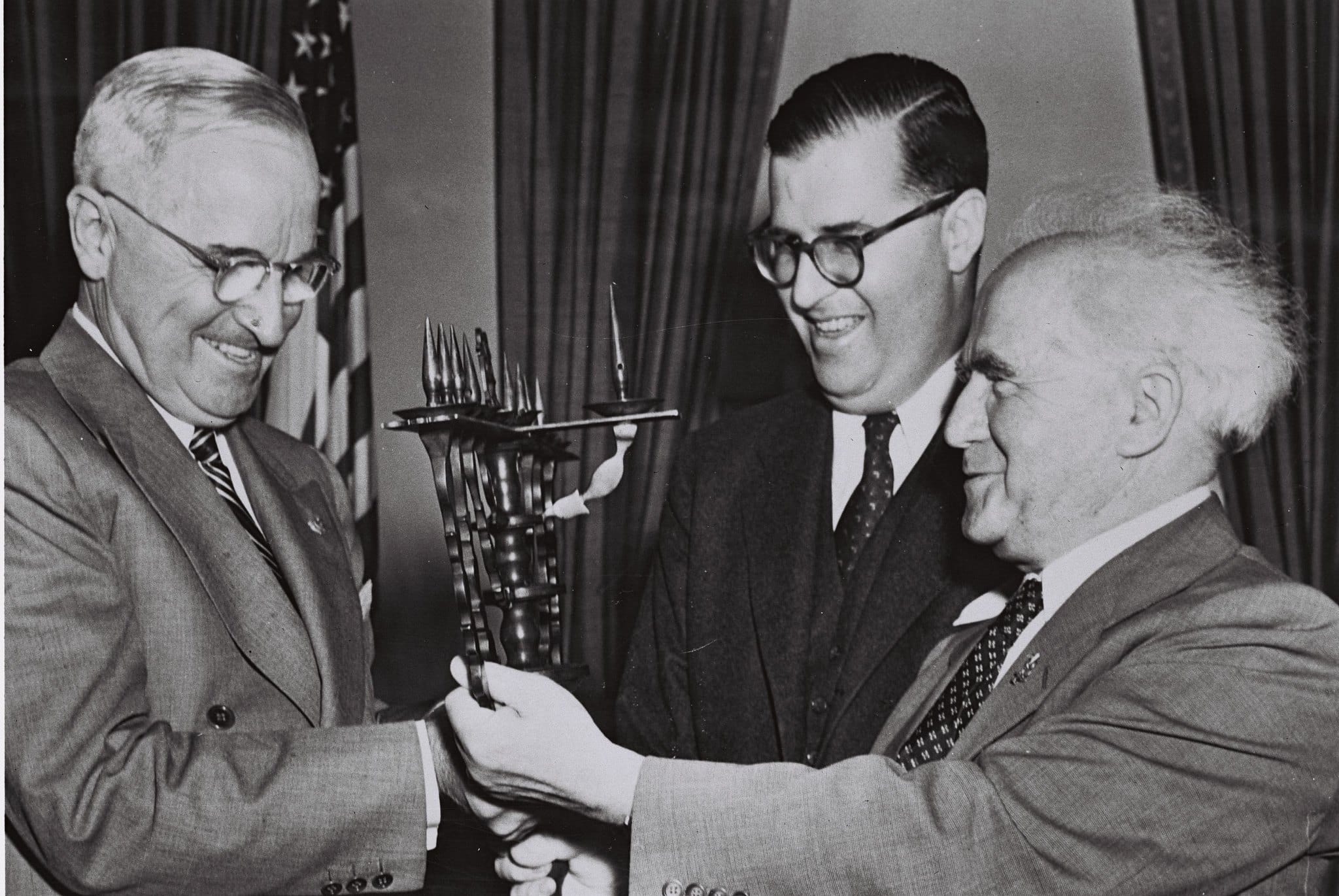

The technical malfunction put the war-time document, dated July 1948, suddenly in an entirely different perspective. The censored version had shown David Ben-Gurion, the prime minister of the brand-new State of Israel, as saying that “I am against the wholesale demolition of villages.” But then, once the blackout was removed, there followed a “but.” Indeed, he quickly elaborated: “But there are places that constituted a great danger and constitute a great danger, and we must wipe them out. But this must be done responsibly, with consideration before the act.”

These comments are testimony of the well-documented ethnic cleansing of Palestine during Israel’s foundational war.1Ilan Pappe, The ethnic cleansing of Palestine (Oneworld Publications, 2006). In fact, the ‘wiping out’ of Arab forces and the “expulsion” of the Palestinians was officially sanctioned policy during the conflict. The censorship, which the Israeli State Archives claims to have been unintentional, is only the latest attempt to obscure this historical crime against humanity.

The Roots of Ethnic Cleansing

David Ben-Gurion is widely celebrated in Israel as the country’s founding father who led the war effort during and after the declaration of independence of May 14, 1948. Travelers flying to Tel Aviv today are immediately reminded of this historic figure as they land in Ben Gurion Airport. But the airport in fact predates the founding of Israel. Established in 1934, Arab and European airlines used Lydda Airport, as it was called before World War II, for local and transcontinental travel. In July 1948, however, the same month as the above-mentioned cabinet meeting, the Israelis seized the airport and gave it a Hebrew name: Lod Airport. In 1973, after Ben-Gurion’s death, it was renamed again to its present name in honor of Israel’s first prime minister.

This is just one tiny example of how Palestinian land—and Palestinian history for that matter—was ‘wiped out’ as a result of the 1948 war. This process, as well as the massive expulsion of Palestinians that went along with it, was not a haphazard outcome of the war, however. Rather, as this article argues, ethnic cleansing was at the root of the Zionist project and was implemented as policy by Ben-Gurion in the late 1940s.

From the very beginning, political Zionism implied the “transfer” of the indigenous population to other countries. In their early efforts to gain support from Western nations, Zionist leaders proclaimed that Palestine was “a land without a people for a people without a land.” In reality, they knew that the first part of that slogan was a lie. The Palestinian people were like “the rocks of Judea, obstacles to be cleared on a difficult path,” as Chaim Weizmann, a prominent Zionist figure and future first president of Israel, put it in 1918.2Nur Masalha, Expulsion of the Palestinians: the concept of ‘transfer’ in Zionist political thought, 1882-1948 (Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992), 5-48. Quote at page 17.

This dismissive attitude towards the pre-existing civilization in Palestine perhaps explains the early Zionist optimism surrounding the “Arab question.” Theodore Herzl, the founding father of political Zionism, believed that the Palestinians could be uprooted with non-violent methods. In 1895, he wrote that “we shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it any employment in our own country.” The property owners, on the other hand, could easily be tricked into giving up their lands according to Herzl. “Let the owners of immovable property believe that they are cheating us, selling us something far more than they are worth. But we are not going to sell them anything back.”3Idem, 8-9.

The free market turned out not to be a very good ally, however. Only 5.8% of Palestinian land was under Jewish ownership by December 1947, more than half a century after Herzl’s remarks. Realizing that Jewish immigration, establishing kibbutzes and buying property was not enough, Zionist leaders soon turned to political and military means.

Political help was secured first. During the First World War, a great-power patron was found in Britain, which pledged to put its weight behind “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” in the so-called Balfour Declaration of 1917. When the British secured a League of Nations mandate over Palestine in 1922, words were followed by deeds. During the Mandate period, the British allowed for the creation of a Jewish Agency to function as a semi-governmental body while denying similar advantages to the Palestinians. As such, the Palestinians had to bear the brunt of two colonial movements simultaneously: a settler-colonialist movement in Palestine, aided and abetted by the world’s foremost colonial power in London.4Rashid Khalidi, The hundred years’ war on Palestine: a history of settler colonialism and resistance, 1917-2017 (Metropolitan Books, 2020), 17-54.

The more extreme branches of the Zionist movement, such as the “Revisionists” led by Ze’ev Jabotinsky, were the first to resort to military means. As far back as 1925, Jabotinsky wrote that “Zionism is a colonizing venture and, therefore, it stands or falls on the question of armed forces.”5Idem, 51. Since he was open about an “Iron wall of bayonets” that needed to separate Jews and Arabs, there was little confusion about the purpose of the paramilitary militias that Jabotinsky endorsed. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Irgun and the Stern Gang launched a terror campaign against Palestinian civilians (and British officials towards the end of the Mandate period) that left hundreds of casualties.

Lest these extreme forms of intimidation be seen as evidence that the need for ethnic cleansing was solely a right-wing policy aim, it was actually accomplished under the leadership of the dominant “Labor” branch of the Zionist movement. With the help of sympathetic British officers, the Jewish Agency was allowed to expand its military arm, the Haganah, during the Great Palestinian Revolt of 1936-1939. Meanwhile, the mainstream Zionist leadership, too, was gravitating towards a military solution to the “Arab Question.” Ben-Gurion, for instance, told his compatriots of the Jewish Agency in June 1938—ten years before the ‘wipe out’ comment—that “I am for compulsory transfer; I do not see anything immoral in it.”6Pappe, The ethnic cleansing of Palestine, XI.

The Execution of Ethnic Cleansing

But how was this “compulsory transfer” to be accomplished? How, indeed, did the Zionists gain control over the majority of Palestine by the beginning of 1949 if a little over one year earlier they owned barely 5% of the land, the majority of which was concentrated in the cities? Here, the political and military clout they had built up over the years converged.

This time, foreign political help came from the recently founded United Nations, which, bear in mind, before decolonization in Africa and Asia was in large part a club of the Western Great Powers. These nations felt obliged to compensate the Jews for the Nazi Holocaust. In February 1947, the British decided to turn the fate of Palestine over to the UN. On November 29 of that year, after nine months of deliberation, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 181, which envisioned the partition of Palestine into two separate states. 56% of the land was to go to a Jewish state, while the Palestinians were left with only 43%. (A small enclave around Jerusalem was to become internationally governed.)

The Palestinians were vehemently opposed to partition, however. They considered it unfair since they held almost all of Palestine and had lived on their lands for generations. Moreover, while only 10,000 Jews would end up under Palestinian governance, 438,000 Palestinians—as well as hundreds of villages and the most fertile land—would end up under Jewish rule overnight. Leaving these Palestinians in the hands of an ideology which had openly vowed to de-Arabize Palestine contributed to the fate that was to befall them.

Indeed, the Palestinian and Arab rejection of the UN plan allowed the Zionist leadership to claim the moral upper hand. Ben-Gurion was a good tactician; like many of his successors, he kept the most extreme Zionist elements at bay and made sure to demonstrate to the outside world that the Jewish side, contrary to the Arabs, did accept the UN plan. Behind closed doors, however, he knew that the borders of the Jewish state “will be determined by force and not by the partition resolution.”7Idem, 36-7.

Still, the two-state solution created a huge problem that preoccupies Zionists until today: the so-called “demographic balance.” Jews would constitute only a tiny majority in the future Jewish state, and this did not stroke with the exclusionary Zionist ideology. As Ben-Gurion said in a speech a few days after the publication of the UN partition plan, “there are 40% non-Jews in the areas allocated to the Jewish state. This composition is not a solid basis for a Jewish state. […] Only a state with at least 80% Jews is a viable and stable state.”8Idem, 48.

And thus, the plan to ethnically cleanse Palestine was born. By the end of the year, parallel to an escalation in terrorist attacks by Irgun and the Stern Gang (and later on also the Haganah), Ben-Gurion gave the green light for lethal assaults on Arab villages. The object was clear: “Every attack has to end with occupation, destruction and expulsion.”9Idem, 64. In early March, ethnic cleansing was adopted as official policy in Plan Dalet (or Plan D), which sanctioned operations aimed at “destroying villages (by setting fire to them, by blowing them up, and by planting mines in their rubble). […] In case of resistance, the armed forces must be wiped out and the population expelled outside the borders of the state.”

It is difficult not to read “in case of resistance” here as a silly pretext. Indeed, in a letter to the commanders of Haganah brigades, Ben-Gurion stated unequivocally that “the cleansing of Palestine [is] the primary objective of Plan Dalet.”10Idem, 128. Moreover, although there was certainly Palestinian armed resistance (and at times acts of retaliation), the systematic ethnic cleansing of 531 villages and eleven urban neighborhoods and towns that followed happened regardless of the presence and activity of Arab armed forces. Hundreds of civilians were killed in dozens of cold-blooded massacres, which, as intended, drove more than 750.000 Palestinians to flee beyond the territory under control of the Israelis. These refugees would never be allowed back in.

The Memory-Holing of Ethnic Cleansing

Like all subsequent assaults on Palestine, Israeli propaganda has done its best to try to paint the Arab-Israeli conflict of 1947-1949 as a defensive war. Echoing later proclamations that the Jews were about to be “driven into the sea,” Ben-Gurion and company justified their military action as a desperate attempt to stave off a “second Holocaust.” In private, however, Ben-Gurion was well aware of the superior military power of the Zionist forces. In a letter from February 1948, for instance, he wrote that “we can face all the Arab forces. This is not a mystical belief, but a cold and rational calculation based on practical examination.”11Idem, 46.

The Lebanese, Syrian, Egyptian, and Jordanian forces that entered Palestine following Israel’s declaration of independence in May 1948 almost exclusively operated in the areas allocated to the Palestinians under the UN partition plan. For the Jordanians, not crossing the UN-proposed borders was even part of a secret deal with the Jewish Agency. But even at defending those borders the Arab forces did a bad job. Indeed, after the war was over the Israelis controlled 78% of historic Palestine, having conquered almost half of the land that was supposed to become part of a Palestinian state. What was left was the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza, the first two of which were annexed by Jordan and the last by Egypt. In 1967, finally, Israel conquered and occupied these areas (as well as the Egyptian Sinai and Syrian Golan Heights), too.

In the procrastinated peace process that has dragged on ever since, the acceptance of the State of Israel within the 1949 armistice lines (the so-called “Green Line”) has formed a sine qua non for the Israelis. Everything that happened before 1967 is considered a fait accompli and is simply not on the negotiating table. Israel, with diplomatic help from its new great-power patron, the United States, to this day ignores UN General Assembly Resolution 194, which affirms the right of return for the millions of descendants of the 750,000 Palestinians it expelled between 1947 and 1949. Meanwhile, under Israel’s 1950 Law of Return, every Jew in the world has the right to “return” to Israel and acquire citizenship.

The fate of the Palestinians that the Israelis failed to expel beyond the borders of historic Palestine is perhaps even more tragic. Palestinians inside the State of Israel, which today make up around 21% of the population, live under a system of Apartheid. Palestinians living in the West Bank continue to live under occupation. And Palestinians in Gaza are confined to what is often called “the world’s largest open-air prison,” suffering at the hands of a devastating fifteen-year-old Israeli-Egyptian blockade and intermittent Israeli bombing campaigns.