The personal savings rate is near seventeen-year lows. Credit card debt is at record levels. Millions of prime-age workers have quit the job market, and full-time employment continues to wither. On the other hand, the Biden Administration wants you to think things have never been better.

Last week, following the release of December’s jobs data by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Biden crowed that “Real wages are up in recent months…and we are seeing welcome signs that inflation is coming down as well.” Biden concluded by saying “it’s a good time to be a worker in America.”

Unfortunately, things aren’t nearly as good as the White House and its accomplices in the corporate media would have us believe.

It’s only a “good time” to be a worker in America if one equates falling real wages and falling full-time employment with “robust” employment conditions.

Moreover, the numbers that the administration continued to cherry-pick to burnish its political image are themselves quite suspect. Response rates to employment surveys sent out by the BLS have gone into steep decline, and the Philadelphia Federal Reserve has recently accused the BLS of vastly overstating employment growth in 2022.

A more sober look at broader economic trends continues to point toward economic pain in 2023, and there is less reason than ever to think that the Federal Reserve will engineer a fabled “soft landing” for the economy after years of record-breaking monetary inflation.

Falling Real Wages, Falling Full-Time Employment

In spite of what Biden may say, real wages in the United States fell, year-over-year from April 2021 to November 2022. That’s likely to also be the case for December once we get the inflation growth numbers for December. Put another way, wages are falling in real terms because the inflation rate has been outpacing wage growth during all that time. Nominal wage growth actually slowed in December according to the new BLS numbers, so unless the inflation rate suddenly collapsed to below 4.5 percent in December—which is unlikely—we will find that real wages fell in December for the twenty-first month in a row.

Another factor pointing to weakness in job markets is the fact that the number of full-time workers fell in December. Nearly all of the gains in workers were part time.

Specifically, full-time employees dropped by 1,000 workers while part-time workers rose by 679,000 (month-over-month). The total gain in all workers for the period was 717,000. Moreover, the overall trend since 2021 is one in which growth in full-time work in general is falling—and turning negative in some months—while part-time employment represents most of the growth.

What does this mean overall? David Rosenberg summed it up in a recent tweet, these are jobs “gains” characterized by part-timers, side giggers, and multiple job holders:

An important aspect of the “household survey” Rosenberg mentions is that it considers part-time workers and barely-employed self-employed people as among the “employed” on a par with full-time workers. Yet, when we consider the reality of slowing wages combined with a lack of growth in full-time workers, one suspects that the employment situation isn’t exactly lucrative for a great many workers. There is also good reason to believe that many workers who are now taking on part-time work are doing so because the cost of living has increased substantially. For example, over the past year, the average hourly wage increased 4.6 percent while CPI prices rose 6.4 percent. Workers are falling behind, and it’s hard to square this with Biden’s claim that workers are doing unusually well.

Stagnant Labor Force Participation

Another reason to suspect the labor market isn’t as great as we’re being told is the fact that total prime-age (i.e., age 25-49) workers are hardly flocking to join the labor force. People leaving the work force could be a sign of a very robust economy, of course, as people can scale back working hours when real wages surge. But its extremely unlikely that’s what’s happening in our current period of rising costs, falling wages, and rising debt.

In fact, the number of prime-age workers “not in the labor force” is still up from where it was before the COVID panic of 2020. In January 2020, about 21.3 million workers labeled themselves “not in the labor force.” That is, these people reported not working for market income at all during the previous year. As of December, the number had risen to 22.2 million. Since the Great Recession began in late 2007, the number of workers not in the labor force is up by more than a million. Biden may think it’s a great time to be a worker in America, but apparently many prime-age workers don’t agree.

This all reflect a larger historical trend in which workforce participation has fallen, with men especially prone to leaving the work force. This all helps to push down the unemployment rate as the pool of potential unemployed workers continues to shrink.

“Jobs” vs. Employed People

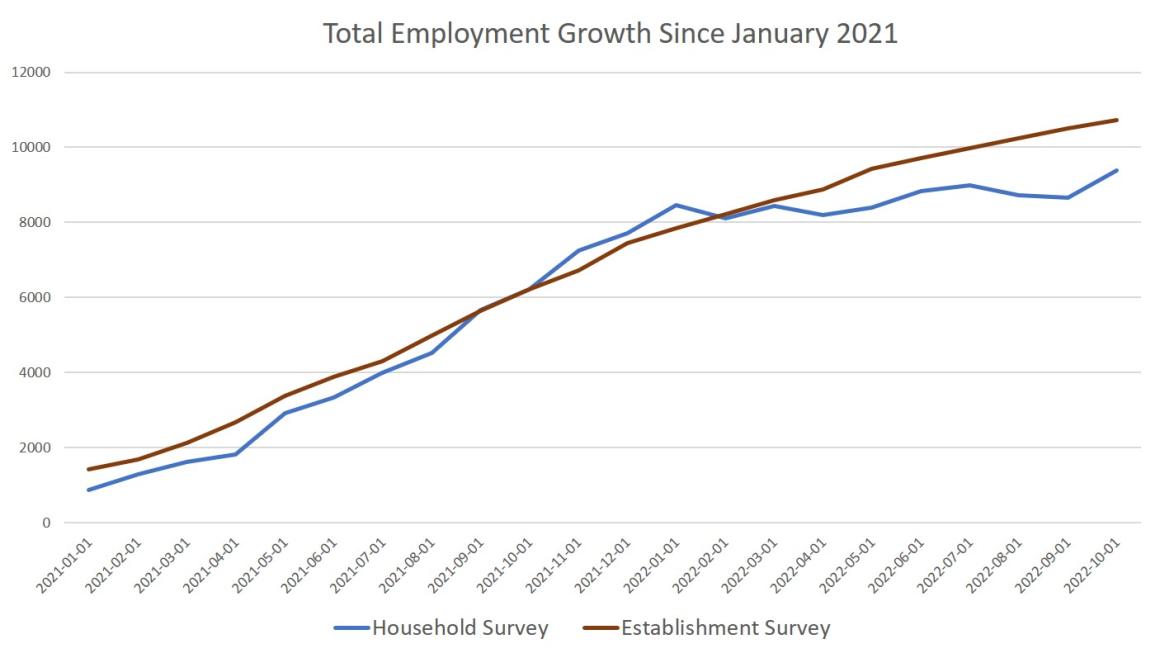

But why is it that we keep hearing about how there is so much job growth? Those “good” numbers are based mostly on a separate job survey which looks only at the number of jobs created, as opposed to the number of employed persons. This means a large number of part-time jobs could be created, with few new employed persons, and this could be reported as robust job growth. In fact, in terms of cumulative employment growth since January 2021, we find a persistent gap between the two surveys. This gap narrowed in December 2022, but, as noted above, this was mostly driven by part-time work. In every month since April 2022, this unexplained gap between employed persons and “new jobs” has ranged from 96,000 up to 1.8 million:

This gap could theoretically be explained by a rising number of multiple job holders, but it seems this need not explain all of the gap, as it seems the establishment survey has been overestimating job growth considerably. According to a new report released by the Philadelphia Federal Reserve the total number of new jobs added during the second quarter was closer to 11,000 than the 1.1 million that the establishment survey had shown. This doesn’t tell us much about the second half of the year, of course, but it does suggests there’s something very wrong with the survey that’s been repeatedly used to “prove” the job market is excellent.

The iffy numbers might have something to do with declining response rates to the BLS’s surveys. Since the COVID panic, the surveys used to collect this data have seen sizable drops in response rates. The establishment survey (CES) response rate has fallen from 59 percent in early 2020 to 45 percent today. The “JOLTS” survey, which produces many rosy estimates about job openings, has fallen to a 30-percent response rate since 2020. In contrast, the Household Survey (CPS) still has a response rate over 70 percent.

Without parsing the data sources, it’s impossible to guess how much the establishment survey’s narrowing data sources are affecting the numbers. In any case, the establishment survey is increasingly delivering estimates that appear questionable given larger economic indicators. The “good” employment data still leaves us wondering why the savings rate is falling and why disposable income is below trend. Why is credit card debt mounting if households are enjoying the fruits of a “strong” labor market?

The writers of Biden’s press releases offer us no answers. Once we take a broader view, however, the numbers point to recession and declining fortunes for a great many of America’s workers. In November, the money supply actually fell, continuing a trend of rapidly falling money-supply growth. That’s a strong recession signal. An even more reliable recession signal is the yield curve showing the 3-month/10-year yield spread. When this goes negative, a recession has been assured in every case for decades. This spread is now the deepest in negative territory it’s been in more than 40 years.

Misplaced Trust in the Federal Reserve

At this point, Wall Street and the regime are both banking on the hope that the Federal Reserve will engineer a “soft landing” through its monetary policy. The idea here is that the Fed will somehow figure out how to allow interest rates to rise just the perfect amount to rein in inflation while also not triggering a recession. This is hope based on fantasies, however. It’s entirely possible a recession may somehow be averted this year or next, but if that occurs, we hardly have any reason to assume the Federal Reserve planned it all. After all, the Fed has made it abundantly clear in the past two years that it has absolutely no special insights when it comes to economic trends or how monetary inflation will affect the economy. After record breaking amounts of monetary inflation in 2020 and 2021, Fed economists were still insisting that price inflation would be no problem and would be “transitory.” Numerous Fed economists from Neel Kashkari to Jerome Powell continued to state that the Fed should keep interest rates low well into 2022, or even into 2023.

By the end of 2021, however, it was clear the Fed has been very wrong about price inflation and was forced to raise rates and promise monetary tightening. Now, they continue to insist they can do so without triggering a recession. The Fed also continued to insist it has no data predicting a recession. This is just par for the course for the Fed which has always predicted good economic times even when the country is in recession. Ben Bernanke, for example, was still denying there would be any recession at all in 2008, even after the U.S. had been in recession for months.

In other words, the Fed is winging it, and the data points to both anemic jobs data and a stagnating economy. The Fed has given us every reason to believe it doesn’t even know what’s going on, and we certainly should not assume it has a secret plan to assure a robust economy into the future.

This article was originally featured at the Ludwig von Mises Institute and is republished with permission.