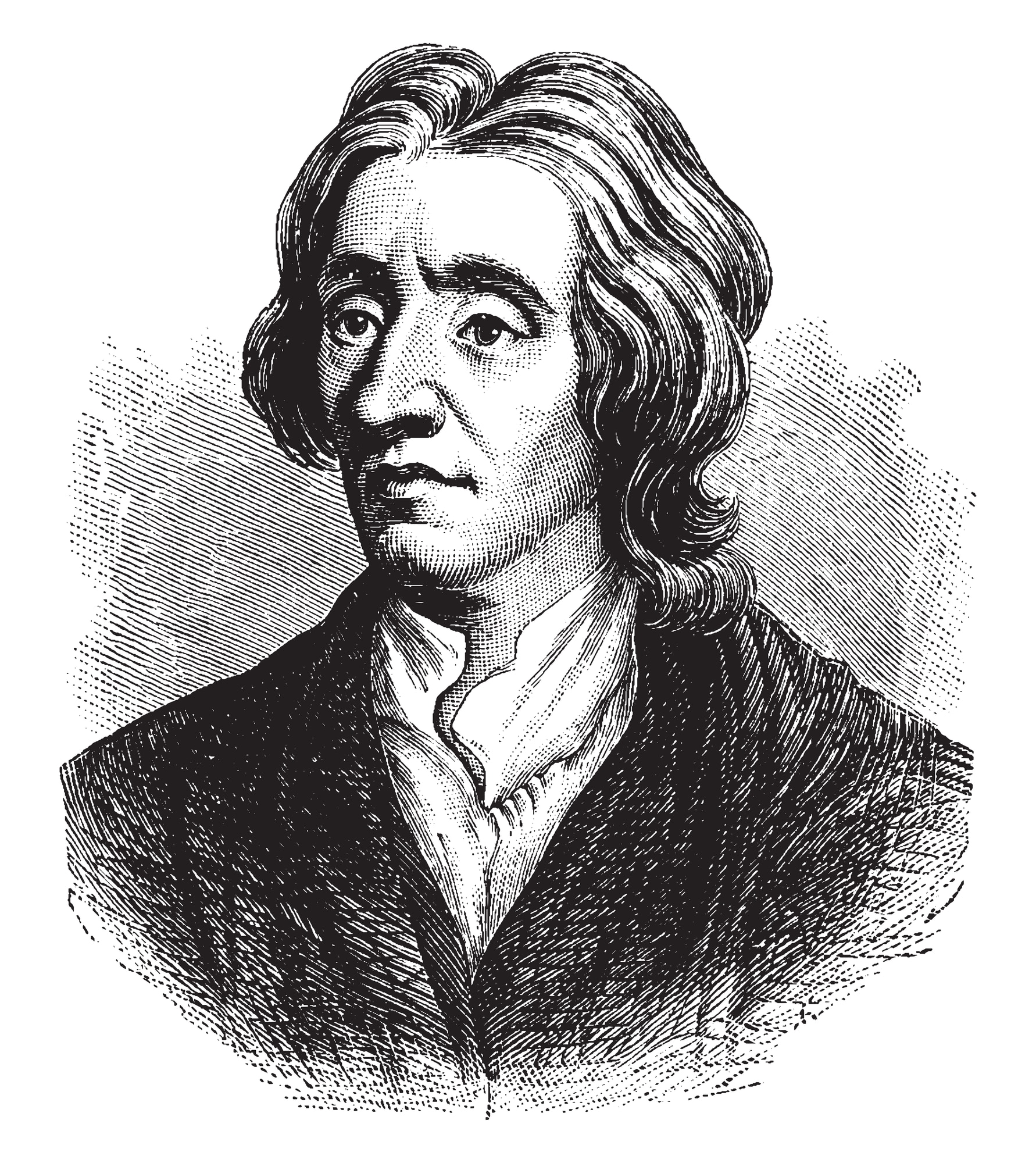

The Enlightenment produced many innovators, but few have left a legacy as contentious and influential as John Locke. Born in Wrington, Somerset on August 29, 1632, Locke wrote the political treatises that shaped England’s Glorious Revolution and later guided the American Revolution. Libertarians still appeal to Locke when debating self‑ownership, property rights, consent, and the scope of government. To celebrate his birthday tomorrow, let’s trace how Locke’s writings help to lay the groundwork for American libertarianism.

Locke’s outlook was forged by experience rather than aristocratic privilege. Born to a Puritan lawyer and educated at Westminster and Oxford, he gravitated toward Baconian empiricism. His association with Anthony Ashley Cooper, later the Earl of Shaftesbury, turned him into a champion of toleration, self‑ownership, and free commerce. When Whig leaders sought to curb royal power, Locke drafted the Two Treatises of Government to justify revolution. Published anonymously in 1689, the Treatises denounced divine‑right monarchy and defended a social contract based on natural rights. By the time he wrote A Letter Concerning Toleration and the Second Treatise, he had concluded that governments derive legitimacy from consent and that individuals retain inalienable rights.

At the heart of Locke’s political thought is the state of nature, a hypothetical condition in which people live without civil authority. Unlike Thomas Hobbes, he did not imagine it as a war of all against all. In the Second Treatise he described it as a state of “perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons, as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature.” Because human beings are naturally equal and independent, no one has a rightful claim to dominate another, and thus “no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions.” The law of nature is not a decree from a magistrate but a rule of reason accessible to all. From it Locke derived duties: each person must preserve his own life and, when this does not conflict with self‑preservation, preserve the rest of mankind.

The state of nature is not a paradise. Without a common judge, disputes may devolve into bias and violence. To avoid these “inconveniences,” individuals consent to form political societies. They entrust governments with authority to enforce the law of nature, but they do not surrender their rights. Law, Locke argued, exists to safeguard liberty rather than abolish it; “…the end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom.” This statement, cherished by modern libertarians, underpins the idea that law can be a friend of liberty rather than its enemy. From this perspective, a legitimate state is limited to protecting life, liberty, and property and must be accountable to its citizens.

Many libertarians regard Locke as the father of the homesteading principle. In Chapter V of the Second Treatise he declared that “every man has a property in his own person.” Because our labour is ours alone, what we mix our labour with becomes ours: “Whatsoever then he removes out of the state that nature hath provided…he hath mixed his labour with, and…thereby makes it his property,” he wrote. This labor‑mixing theory justifies original appropriation: clearing land, harvesting wild fruit, or digging wells turns unowned resources into private property. Locke argued that such appropriation benefits humanity because cultivated land yields more food than it did in common; he even claimed that a person who encloses and cultivates land “may truly be said to give ninety acres to mankind.”

Locke added an important qualification that libertarians continue to debate: appropriation is legitimate only when there is “enough and as good left in common for others.” Robert Nozick adapted this proviso to argue that taking unowned resources is permissible so long as others are not made worse off. Murray Rothbard instead treats self‑ownership and first use as axioms and claims these principles underlie the entire free market. Some egalitarian libertarians invoke the proviso to justify redistribution and environmental limits, while others see it as compatible with robust property rights. Despite these debates, Locke’s theory ties property to human labor and self‑ownership, and he insisted that self‑ownership is inalienable and cannot be wholly transferred to government.

Locke’s natural law ethics leads directly to his doctrine of consent. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, the most direct reading of his theory finds that “the concept of consent [plays] a central role.” People become full members of political societies through express consent, which might include pledging allegiance or participating in civic life. Tacit consent—using public goods or traveling on highways—binds individuals while they benefit from state services but may be withdrawn by emigration. Locke’s insistence on actual consent has led some critics to label him a philosophical anarchist because it implies that people who never consented remain outside political obligation.

The same logic yields Locke’s doctrine of revolution. When government exceeds its delegated powers by violating natural rights, it dissolves the social contract and authority reverts to the people. This right is not an invitation to disorder but a safeguard against tyranny. Historian Jim Powell notes that Locke “insisted that when government violates individual rights, people may legitimately rebel.” The radicalism of this view forced Locke to publish anonymously and admit authorship only in his will. The right of revolution would resonate with the American colonists and become enshrined in their founding documents.

Locke was equally concerned with freedom of conscience. In A Letter Concerning Toleration, he argued that the church and the state have distinct roles: the church is a voluntary community concerned with salvation, while the state protects civil interests such as life, liberty, and property. George H. Smith summarizes Locke’s position: Jesus and his apostles spread the Gospel by persuasion, not force; if Christ had wanted to use coercion, he could have called “armies of heavenly legions.” Thus tolerance toward religious dissenters is agreeable both to the Gospel and to “the genuine reason of mankind.” Forcing belief breeds hypocrisy rather than genuine faith.

Locke’s toleration was not unlimited—he excluded atheists, whom he thought could not be trusted to keep oaths—but his separation of civil and ecclesiastical authority laid the foundation for later libertarian defenses of freedom of conscience. His insistence that persuasion, not compulsion, is the proper means of spreading religious truth anticipated the libertarian distinction between voluntary association and coercion.

Perhaps no philosopher influenced the American Revolution more than Locke. Thomas Jefferson ranked him among the two most important thinkers on liberty. According to Powell, Locke’s writings “fired up George Mason and provided James Madison with his fundamental principles of liberty and government.” The same biography recounts that Benjamin Franklin studied Locke during his self‑education and John Adams believed Locke should be studied by both girls and boys. Writing for Econlib, Richard Gunderman remarks that Locke was “probably the single thinker who exerted more influence over the American founders than any other.”

Locke’s influence is visible in the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson’s famous phrase “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness” echoes Locke’s triad of “life, liberty, and estate (property).” The Declaration’s assertion that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed and that people may alter or abolish governments that violate their rights reflects Locke’s doctrines of consent and revolution. His emphasis on separation of powers and majority rule informed the United States Constitution. While the framers diverged on particulars—Locke proposed property‑based suffrage and a more limited legislature—their reliance on his ideas is unmistakable.

After independence, Lockean language continued to permeate American politics. Cato’s Letters, essays by John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, disseminated Lockean arguments for natural rights and limited government. Pamphleteers like Thomas Paine drew on Locke’s theory of rebellion, and the Bill of Rights institutionalized concerns about individual liberties and the dangers of concentrated power.

Locke’s relevance did not wane with the eighteenth century. Twentieth‑century libertarians built upon his natural rights framework to articulate theories of minimal government and, in some cases, anarchism. John Rawls and Robert Nozick both acknowledged their debt to Locke. Nozick’s Anarchy, State, and Utopia begins with the assertion that individuals have inviolable rights and proposes a minimal “night‑watchman” state that protects those rights. He explicitly invokes Locke’s idea that acquisition of unowned resources is justified by labor mixing and that appropriation is legitimate if it does not worsen others’ situations.

Ayn Rand, though wary of the libertarian label, drew heavily on Locke. The Ayn Rand Lexicon calls him the most important philosopher influencing American political institutions. Rand’s concept of individual rights as moral principles sanctioning freedom of action echoes Locke’s natural rights. Her heroes pursue productive lives free from state interference, and her essays emphasize that the initiation of force is morally wrong. She praised the Founding Fathers for basing a political system on the premise that the individual precedes the state.

Murray Rothbard and other radical libertarians pushed Locke’s ideas further. In The Ethics of Liberty, Rothbard argued that self‑ownership and homesteading suffice to derive a libertarian social order and insisted that any state monopolizing coercion is unjust. His claim that these axioms “establish the morality and the property rights underlying the entire free market economy” draws directly from Locke. Later writers have tried to reconcile Locke’s proviso with modern worries about inequality and environmental harm and have highlighted that ownership entails duties not to harm others or leave them without means.

Interpretations of Locke vary. Some emphasize his invocation of God and moral duties, suggesting that his theory is less individualistic than later libertarian readings. Critics also note his silence on the rights of women and enslaved people. Yet even skeptics concede that his natural law framework remains the starting point for debates about property, the state, and individual rights.

On the anniversary of his August 29 birth, John Locke deserves more than ritual praise. He was not a prophet of unbridled individualism but a philosopher who grounded rights in human nature, insisted that government serves the governed, and recognized duties alongside rights. His maxim that no one ought to harm another in life, health, liberty, or possessions and his warning that the end of law is to “preserve and enlarge freedom” remain moral touchstones. Americans from Jefferson and Madison to modern libertarians have drawn inspiration from his natural rights philosophy. In current debates over property, regulation, and liberty, Locke’s insistence that power rests on consent and that law protects freedom offers a framework for reform and a reminder that common sense is itself philosophical.