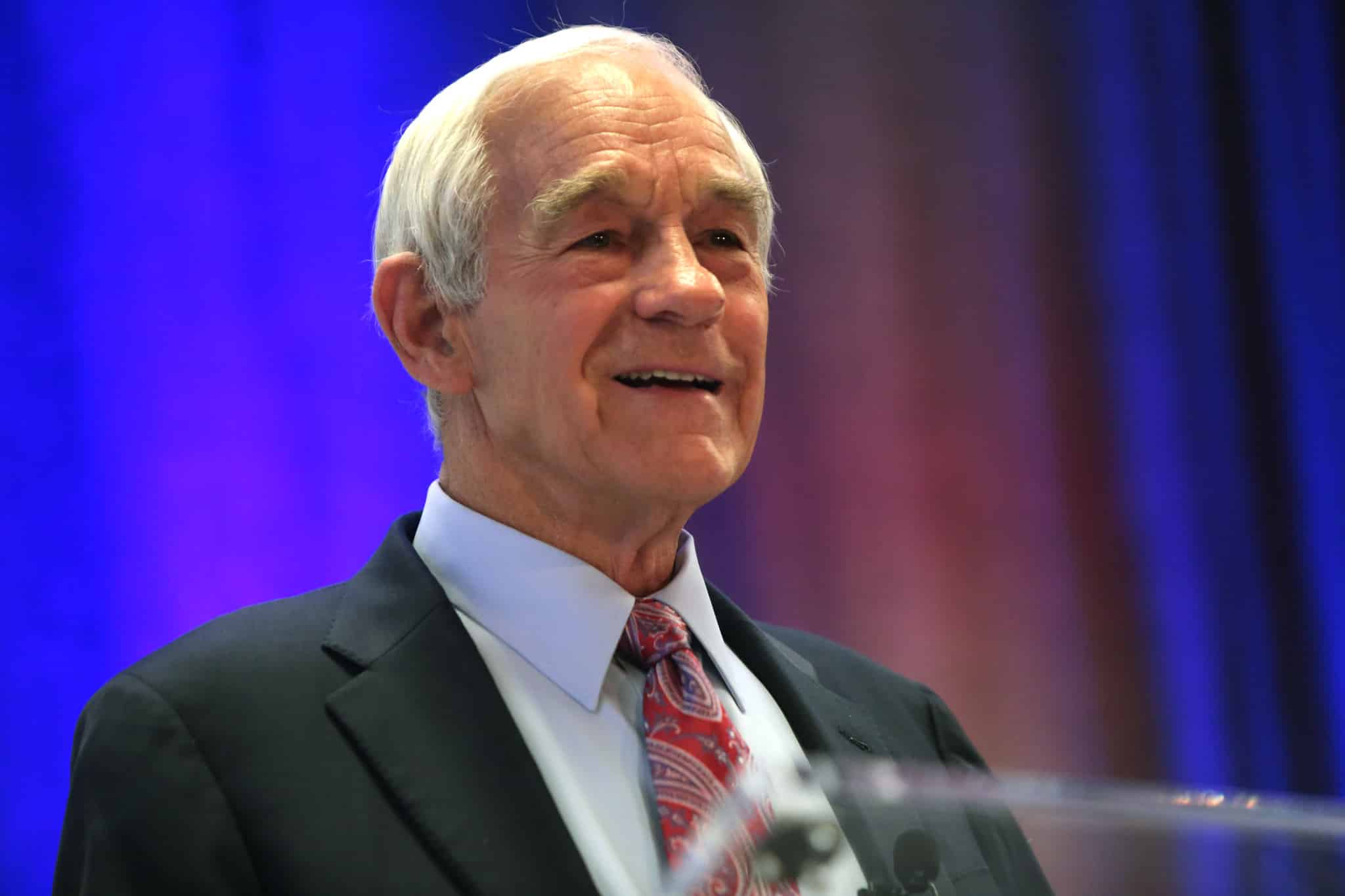

In a political age that prizes charisma over conviction, Ron Paul’s career stands out as a long series of principled noes. The Texas physician–turned–congressman won his first seat in 1976, lost it a few months later, then returned repeatedly to the House, always as an outsider and always carrying the same simple message: the federal government must be bound by the Constitution, money must be sound, markets must be free, and peace is a moral imperative. As he turns ninety today, it is worth revisiting how a soft‑spoken obstetrician came to inspire a movement that outlived his political campaigns, and why he deserves to be counted among the most influential libertarians of the modern era.

Paul’s moral consistency is legendary. Born in Pittsburgh in 1935 and trained as a doctor, he served as a flight surgeon in the U.S. Air Force before establishing a medical practice in Texas. His early reading of Friedrich Hayek, Murray Rothbard, and Leonard Read convinced him that expansive government and fiat money were incompatible with liberty. When President Richard Nixon closed the gold window in 1971, Paul later wrote, he knew “the stage was set for the 1970s inflation and for the political chaos that would follow,” so he entered politics to champion sound money and limited government. Over more than two decades in Congress he would never vote for a tax increase, never vote for an unbalanced budget, and never vote to raise congressional pay.

Such obstinacy made him politically lonely, but it also gave him credibility. In his farewell address to Congress in 2012 he warned that Washington’s spending binge rested on a bipartisan bargain. “One side doesn’t give up one penny on military spending, the other side doesn’t give up one penny on welfare spending, while both sides support the bailouts and subsidies for the banking and corporate elite,” he told his colleagues. With typical understatement he added that his 1976 goals—“promote peace and prosperity by a strict adherence to the principles of individual liberty”—remained unchanged. That fidelity allows his admirers to call him the “Dr. No” of the House with affection rather than disdain.

Paul’s libertarianism begins with the text of the Constitution. In a 2011 speech titled “True Fidelity to the Constitution,” he argued that Congress has “justified every conceivable expansion of the Federal Government” by misinterpreting the General Welfare Clause, the Interstate Commerce Clause, and the Necessary‑and‑Proper Clause. Such distortions, he said, allow members to treat the Constitution as a “living document” they can bend to suit political expediency. The remedy, Paul insisted, is not civic cheerleading but an honest reassessment of policy: no more wars without an actual declaration from Congress; repeal the Federal Reserve Act; respect gold and silver as legal tender; abolish unconstitutional departments like Education, Commerce, and Homeland Security; repeal the PATRIOT Act; and restrain the Transportation Security Administration. He pointedly asked whether Americans possess the moral character to demand such changes and whether politicians have the courage to refuse special interests. Without love of liberty and respect for the rule of law, he warned, the Constitution is “a worthless piece of paper.”

To him, enumerated powers were not a rhetorical flourish but a bulwark against tyranny. When many conservatives argued that the general welfare clause authorizes vast spending, Paul reminded them that Article I lists only eighteen federal powers and leaves education, retirement, and health care to the states or the people. If fidelity to the Constitution is “cranky,” he mused, then so were James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington.

Paul’s libertarianism also rests on a classical understanding of markets. In a column published after Hurricane Sandy in 2012, he defended so‑called “price gouging.” When the government imposed gasoline price caps, he observed, miles‑long lines formed and a black market flourished; had gas stations been allowed to raise prices, those most in need would have bought fuel and outside suppliers would have rushed in. “Prices perform an important role in providing information, coordinating supply and demand, and enabling economic calculation,” he wrote. Interfering with the price mechanism always leads to shortages, and no legislature can repeal the laws of supply and demand.

Paul extends the same logic to money itself. In End the Fed, he explains that crowds chanted “End the Fed” not because he incited them but because the Federal Reserve creates money out of thin air, depreciates the dollar, and has not prevented business cycles. He argues that the Fed wields “ominous power with no oversight” and that paper money is unconstitutional; only gold and silver are legal tender. Inflation, he warns, is regressive: it benefits bankers and government contractors while hurting savers, encourages protectionism, and finances wars. The solution, he believes, is to restore a free market in money, allow competing currencies, and gradually return to a gold standard. When central bankers and politicians have no ability to inflate, government must live within its means.

Paul applies his economic creed consistently. He opposed the bank bailouts of 2008 and 2020, argued against corporate subsidies, and denounced deficit spending regardless of the party in power. Even when asked to back popular price controls—for example on gasoline or pharmaceuticals—he refused, explaining that such interventions misallocate resources and harm the poor. Unlike some libertarians who see a role for targeted regulation, Paul seldom deviates. His critics label him dogmatic; his admirers call him principled.

No aspect of Paul’s philosophy has generated more controversy than his foreign policy. While most of his Republican colleagues embraced interventionism, Paul called for non‑intervention and invoked the Golden Rule. In the 2007 Republican primary debate, former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani denounced Paul for suggesting that U.S. foreign policy contributed to the 9/11 attacks. Unfazed, Paul asked Americans to imagine how they would react if China crossed the ocean, demanded bases on U.S. soil, and tried to dictate American life: even if the Chinese had good intentions, he argued, “we would all be together and we’d be furious.” The exchange illustrated his belief in “blowback”—that military interventions create unforeseen and often violent repercussions.

Paul first articulated this thesis during the Cold War. In his 2002 House speech opposing the authorization for use of force in Iraq, he noted that Iraq posed no threat to national security and that preemptive war would set a dangerous precedent. He warned that war without an act of aggression and without exhausting diplomatic options violated the just war doctrine. Echoing Madison, he reminded Congress that the executive branch is predisposed to war. History vindicated his fears: the Iraq War cost trillions of dollars, destabilized the Middle East, and fuelled global anti‑American sentiment.

Paul’s anti‑war stance is inseparable from his defense of civil liberties. In a 2011 speech at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) he lambasted the PATRIOT Act as “the destruction of the Fourth Amendment.” He argued that fiscal conservatives should look critically at U.S. support for dictators; in Egypt alone, Washington spent $70 billion propping up Hosni Mubarak, only to see his regime toppled and the money siphoned into Swiss accounts. He described foreign aid bluntly as taking “money from the poor people of a rich country and giving it to the rich people of a poor country” and called for friendships and trade while avoiding “entangling alliances.” Paul lamented that the United States maintained troops in 135 countries and nine-hundred bases and insisted it was time to “bring troops home.”

Critics accuse Paul of isolationism, but he responds that non‑intervention is not isolation. Trade, travel, diplomacy, and cultural exchange flourish in peace. He notes that the Soviet Union collapsed because of economic failure, not because the United States fought a land war in Eastern Europe. Heavy military spending weakens the economy, fosters debt, and expands the state. As he told CPAC attendees, many conservatives will not cut a penny of military spending, “and the military is not equated to defense”; President Dwight Eisenhower himself warned of the “military–industrial complex.”

Paul’s messaging alienated many Republican voters. During the 2012 South Carolina debate he urged the audience to apply the Golden Rule—“treat other nations as we would want them to treat us”—and quipped that if Americans do not want others to ban U.S. oil imports, they should not ban Iran’s. He expressed puzzlement that the term “golden rule” elicited boos. The conservative electorate jeered, and Texas Governor Rick Perry joked that the moderator should cut off Paul with a gong. Yet the moment became an emblem of his courage: alone among the candidates, he dared to apply a moral principle to foreign policy.

But for his supporters, these exchanges are badges of honor. Paul stood on the same stage as frontrunners, refused to parrot applause lines about American exceptionalism, and quoted Jesus’ admonition from the Sermon on the Mount to treat others as we would wish to be treated. His critics called him naïve; his defenders noted that past presidents as diverse as John Quincy Adams and Dwight Eisenhower made similar points. That he was jeered by his own party speaks not to his wrongness but to the state of political discourse.

Paul’s critics like to portray him as doctrinaire, but his morality is rooted in empathy. He opposes war because it kills innocents and breeds resentment; he opposes the draft because it treats young people as property of the state; he opposes asset forfeiture because it strips citizens of property without due process; he opposes drug prohibition because it cages non‑violent offenders and fuels racial disparity. His stance against civil asset forfeiture, the drug war, and the draft is not pragmatic but principled—government should not coerce unless an individual violates another’s rights.

This defense of the powerless extends to financial policy. Paul notes that inflation, deficits, and bailouts are hidden forms of taxation that punish the poor. When Congress authorizes spending it cannot fund through taxes, the Federal Reserve monetizes the debt; the resulting price inflation reduces the purchasing power of wages and savings. By contrast, those close to the Federal Reserve—the banks and corporations receiving cheap credit—profit. Paul thus frames central banking as a form of class warfare.

Ron Paul is not a typical politician; he is a moral philosopher who happened to hold office. His critics mock his consistent voting record as cranky and quixotic, but the record testifies to a rare integrity. He opposed war when both parties cheered; he condemned the Federal Reserve when few understood it; he warned about surveillance long before Edward Snowden’s revelations; he criticized corporate welfare; and he rejected the false choice between safety and liberty. He treated opponents with civility even when dismantling their arguments. He inspired a movement without demanding a following. In an era of shifting positions and pragmatic compromises, he stands as a model of uncompromising ethical consistency. That is why, as he celebrates his ninetieth year, the libertarian movement he galvanized continues to grow.