To live is to act. To act is to choose. To choose is to prefer. To prefer is to pursue values—that is, to value. That’s logic-guided observation. Ego sum, ergo aestimo: I am, therefore I value. (HT: Aristotle, Ayn Rand, and Ludwig von Mises.)

Next: to think is to act. “[T]hinking itself [is] an action,” Ludwig von Mises wrote in Human Action, “proceeding step by step from the less satisfactory state of insufficient cognizance to the more satisfactory state of better insight.”

Shortcut: to think is to value. (James Ellias of Inductica calls this the “value axiom.”) Like it or not, we’re immersed in the world of “ought.” To assert a proposition is to imply: “This is true, so you ought to pay heed.” That’s the case even if your proposition is something like, “‘Ought’ statements have no cognitive content.” Hume and his fellow emotivists were and are wrong.

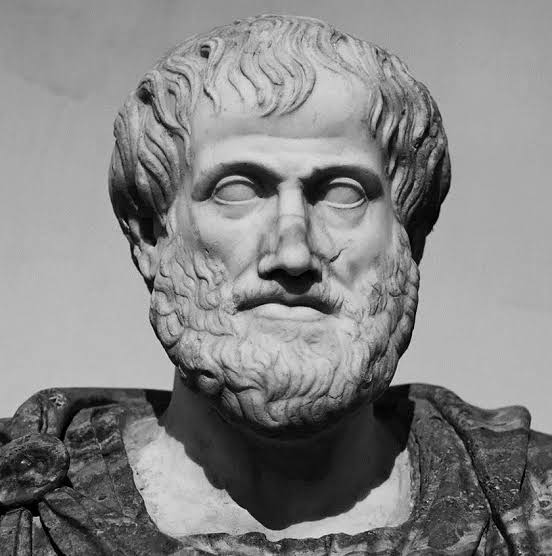

Aristotle noticed that human action in the pursuit of ends that are not sought for their own sake—but rather are sought as means to further ends—must aim at some ultimate end: the good life, happiness, contentment, call it what you will. Otherwise, you’d have an infinite series of means leading nowhere, which would make no sense. As he put it:

If, then, there is some end of the things we do, which we desire for its own sake (everything else being desired for the sake of this), and if we do not choose everything for the sake of something else (for at that rate the process would go on to infinity, so that our desire would be empty and vain), clearly this must be the good and the chief good…. [W]e call final without qualification that which is always desirable in itself and never for the sake of something else…. Now such a thing happiness, above all else, is held to be; for this we choose always for self and never for the sake of something else…. Happiness, then, is something final and self-sufficient, and is the end of action.

Note the irony: morality is associated with choice and free will. But “[f]or Aristotle, this ultimate end or good is not chosen; it is implicit in every desire and every choice, and all our other ends are to be understood as subordinate to it. The end is, as it were, forced on us; and the task of practical reason is simply to identify it,” Roderick T. Long writes in Reason and Value: Aristotle versus Rand. (Emphasis added.) The ultimate end, therefore, is not pre-moral. Since we are fallible, we need practical reason to make sure the means we select are suited to the ultimate end.

This brings us to political theory and the objective case for freedom. Spoiler alert: as acting, thinking, choosing, valuing beings, we need liberty. But each person needs more than liberty for himself. He needs it for everyone else. Why? Because value pursuers need facts, knowledge, and truth (oh that word), and no individual can acquire all the relevant information on his own.

I’m drawing on Frank Van Dun’s 1986 paper “Economics and the Limits of Value-Free Science.” Van Dun points out that economics is value-free in the sense that economists’ values should not shape how they observe market phenomena. For example, even someone who dislikes markets for moral or aesthetic reasons should be able, in principle, to see that tariffs raise prices and shrink supply. However, no science, including economics—no truth-seeking project—can be value-free in a broader sense: its practitioners must value truth seeking and conduct themselves accordingly.

The bridge from there to politics is the fact that all truth seeking, even the mundane, everyday sort we all engage in, is a social process. This is not to deny individualism. It’s a recognition that individuals cannot truth-seek alone. We learn from what others say and do. The self-interested truth seeker needs others to check him, for it is too easy to slip into complacency without realizing it. As Van Dun puts it,

There is no way an individual can break out of the prison of “the evident,” no way he can even identify, let alone begin to question, his prejudices, unless he has come to understand that what is evident to him may not be evident to another and that his point of view is not the only one. Science is a dialogical undertaking: it requires that we make public what we think and try to refute what we believe we ought not to accept, and try to prove what we believe we ought to believe — it requires that we give our reasons.

…A dialogue is an argumentative, not a persuasive, not a rhetorical exchange: the aim of participation is to understand others in order to make one oneself understood in order to allow others the opportunity to indicate just why their understanding of one’s point of view does or does not appear to them sufficient reason to share it.

John Stuart Mill put it nicely in On Liberty: “He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that.”

This suggests a self-interested “ethics of dialogue,” which a truth seeker is committed to by his own search for truth. (This is in the spirit of Aristotle; see Roderick Long’s paper linked to above.) It is a code, Van Dun writes, “to allow others to question one’s most sincere convictions … to refrain from using rewards or punishments—promises or threats—as means for securing the agreement of others; to refuse to argue against one’s better judgment; and to insist that others do likewise. But most of all: to respect the dialogical rights of others—their right to speak or not to speak, to listen or not to listen, to use their own judgment.”

That we ought to respect these rights, recognized in the practice of science, follows from the fundamental norm that we ought to be reasonable—that one ought to respect rational nature, both in oneself and in others; that one ought to cultivate one’s own reason and ought to allow others to do the same. This requirement of respect for the rational autonomy of every participant turns the dialogue into the primary political institution for preventing prejudice from establishing itself as an impregnable barrier against free and independent thought, and so for making science possible.

Fine, the critic might say, but what has this got to do with the rights of people who are not scientists and philosophers? Van Dun anticipates this objection: “[T]he requirement of reasonableness applies across-the-board to every human endeavor. It applies to action no less than speech. Human action always rests upon and involves judgment. Scientific or theoretical knowledge is not essentially or qualitatively different from ‘ordinary’ or practical knowledge.”

He quotes Ludwig von Mises in this regard: Production “is not something physical, material, and external; it is a spiritual and intellectual phenomenon…. Man produces by dint of his reason…: the theories and poems, the cathedrals and the symphonies, the motor-cars and the airplane.”

“There is, then,” Van Dun adds, “a glaring inconsistency in the views of those who defend ‘free speech’ and ‘the free market of ideas’ but attack freedom of action and the free market in goods and services.”

Respecting reason entails respecting persons. But respecting persons requires more than respecting their bodies. In pursuit of their projects in a finite world, people need to transform matter into means to their ends, endowing those things with purpose. They cannot pursue projects or respect others’ pursuits if they cannot know what objects they may use by right, that is, without permission. “In order to respect others as rational agents we must know the distinction between ‘mine’ and ‘thine,'” Van Dun writes. “…If we are to respect the person we ought to respect what is his, otherwise we would deny him the right to act on his own judgment, and thereby destroy the dialogical relationship.”

This upends a common argument against private property, namely, that a land owner aggresses against others by excluding them; thus, it is said, nonaggression implies collective ownership. But this is wrong. The first to mix his labor with an unowned parcel transforms a mere thing into a means to an end. Further, the homesteader aggresses against no one in the process. If someone else interferes, he is the aggressor by withholding respect from the homesteader. This is not a matter of arbitrary definition. It is a fact—for if the first person to transform the parcel has no right to it, how can the second person to come along have a right? (This is not to deny that property law is complicated and that details would be shaped by local custom. But a coercive monopoly government is unqualified for that job. It takes a competitive market to get it right. See David Friedman’s The Machinery of Freedom for details.)

The appeal of Van Dun’s argument is palpable. It might look like an additional case for freedom, but it seems more like another demonstration that freedom is an objective condition for the life of man qua rational being. (I commend Rand’s case read in conjunction with Roderick Long’s Reason and Value. By the way, Van Dun’s case is not to be confused with dubious “argumentation ethics,” which holds that the very act of making an argument logically commits one to the self-ownership rights of one’s interlocutor. That’s reality-detached rationalism.)

The upshot is that a truth seeker undercuts his own project when he advocates government interference with other truth seekers, aka everyone else. He thereby relinquishes his truth-seeker credentials.

(I first explored Van Dun’s paper years ago at the Foundation for Economic Education website.)