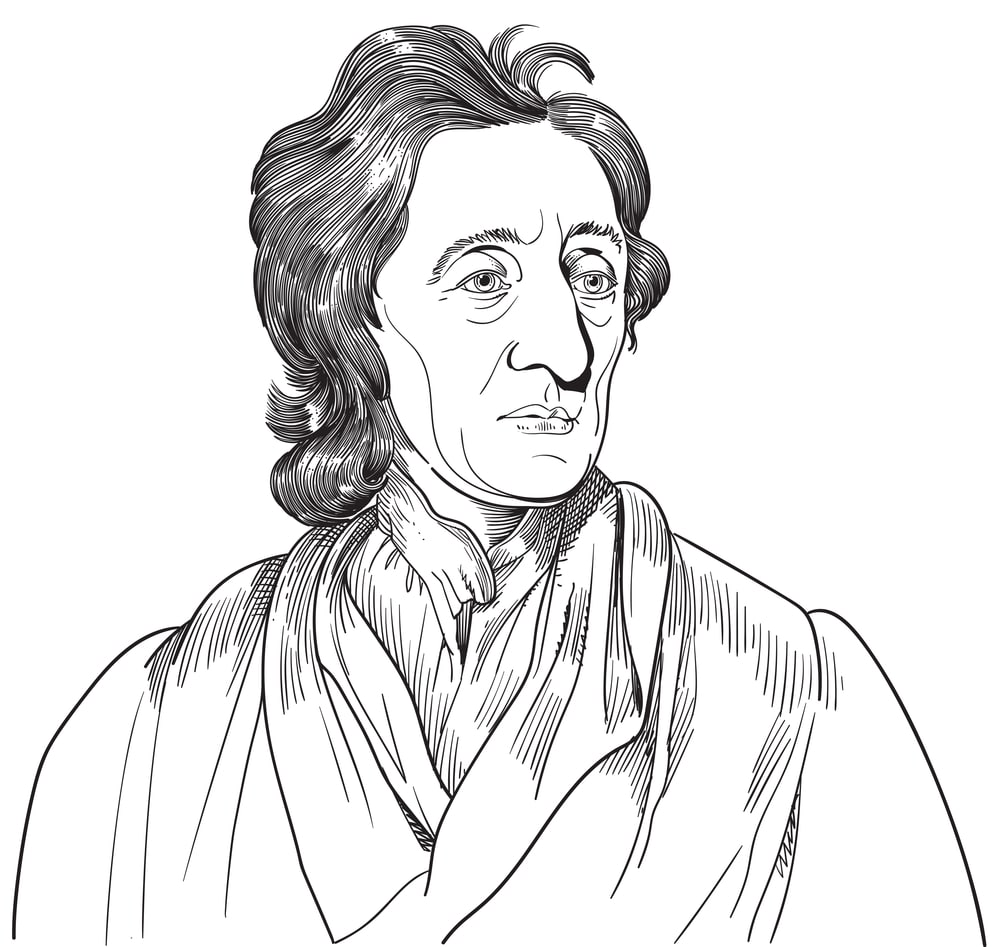

The classical liberal revolution, starting in the 1600s and continuing through the 1700s, created a new ideal for government. Instead of hoping for just rulers who limited the use of their sovereign power, thinkers like Algernon Sidney, John Locke, and many of the American Founding Fathers aimed at a different goal: government derived from the idea of a sovereign people and carefully established to serve their interests. Many of these thinkers saw government as a necessary evil: a coercive force with just enough power to deal with criminals, enforce contracts, and defend the people from foreign attack.

The American founders envisioned a federal government strictly limited by powers enumerated in a written constitution, held in check by the more powerful (yet still limited by written constitutions) states and the people. These states created the federal government to ensure free trade across state lines and military cooperation against other encroaching governments. At least, that was what they told the people at the time.

A government with such limited powers can serve diverse peoples because it legislates on few issues, and no issue it touches presents significant disagreement. This was the Lockean ideal.

However, the incentive for any coercive state is to grow its power. The ways it does so are numerous, ranging from the simple incentive for power-hungry individuals to seek power and abuse it to whatever limit they can get away with, to the tendency for the words in any written constitution to be reinterpreted, redefined, and even ignored as time goes on. When a state decides its own limits, it will expand them whenever it can. As its power grows, special interest groups clamor for legislation providing them rents or giving them control over various issues. The body of laws grows, and self-contradictions become rampant, allowing judges to reach any desired conclusion by selective interpretation.

This creeping growth of state power is what eventually creates a situation in which the state cannot serve all of its people. Imagine some issue X, where some side Y is legislated and enforced. The people on the opposing side lose out; the government no longer serves their interests in this matter. At first, the legislature works with a light touch on issues affecting small minorities and evoking little passion. The people who lost out grumble, but they are too few or care too little to make an issue of it.

Once a law is in force, repeal and the state’s exit from enforcing the issue is rare. The resulting differences encourage political polarization and, ultimately, culture wars. The most enthusiastic busybodies find themselves drawn toward government jobs as an outlet for their moralizing instincts, and they bring along an entire slew of issues they wish to “solve” through state action.

As time goes on, laws touch on larger and more important issues. Government overreach hits larger minorities on issues they care more about. Eventually, the state makes a binding decision on an issue with which a large minority vehemently disagrees. The government no longer serves these people, in their estimation. In fact, the government cannot serve these people—it is legally committed to a position they see as morally repugnant, and that decision may sit on decades of tiny steps, legal precedents, and political polarization that makes reversal nearly impossible.

This breaks the Lockean delusion of the state as a servant of the people. Instead, it tyrannically enforces the preferences of some people against others. It disenfranchises minorities on more and more issues. They face a difficult choice: permanent existence as second-class citizens, forced to pay for actions they see as inexcusable, or to resist and separate from or take over the overgrown state. The state, on the other hand, free from the chains of the Lockean ideal, dedicates itself to forcing these minorities to submit.

What these people have is not representative democracy, or a republic, or any other system promoted by the ideals of classical liberalism, a love of liberty, or respect for the individual. They face an entrenched despot, and many of them see more justice in reversing the state’s position than reducing its power. Occasional limited victories are tempered by bureaucrats or judges in insulated posts and handy legal precedents. Eventually, this despotism may lead to physical violence, and physical violence against the state rarely improves the situation.

The state generally does not cede power back to the people. The influx of the power-hungry into lofty positions prevents that. Continuous political battle between passionate ideological factions wastes the people’s time and energy, impoverishes them, and gives the state opportunities to usurp even more power. Even assuming the state eventually collapses under the weight of its own iron fist, countless people will be hurt in the process.

Secession is one of the best ways to restore the Lockean ideal, at least temporarily. It allows groups to go their own ways when they are too much at odds to share a coercive state. The formerly-oppressed group can come together on the other side of some issue or set of issues, and adjust their founding documents accordingly. If any subgroups wish to go their own way, this gives them an opportunity to do so.

However, even those who are in favor of state policy gain by this maneuver. They gain the ability to further their own political goals with a population that actually believes in them. They no longer have to waste time and energy fighting with the other group politically. And, once tempers cool off, they can trade with the newly-established groups to mutual benefit, without having to listen to their opinions.

Taken to its logical conclusion, the principle of secession leads to a close approximation of the libertarian ideal. Far fewer people are forced to remain subject to states they believe are deeply opposed to their moral values or their flourishing. Smaller, decentralized states are less likely to have massive military might to oppress their neighbors or their own people. More numerous states give people more opportunities to find communities they fit in with. Less political bickering saves the people’s time and energy to apply it to more productive ends. It is the solution that only tyrants can oppose—and no one is obligated to obey the orders or preferences of tyrants.