Is Medicare a good program, financially speaking, for ordinary working people?

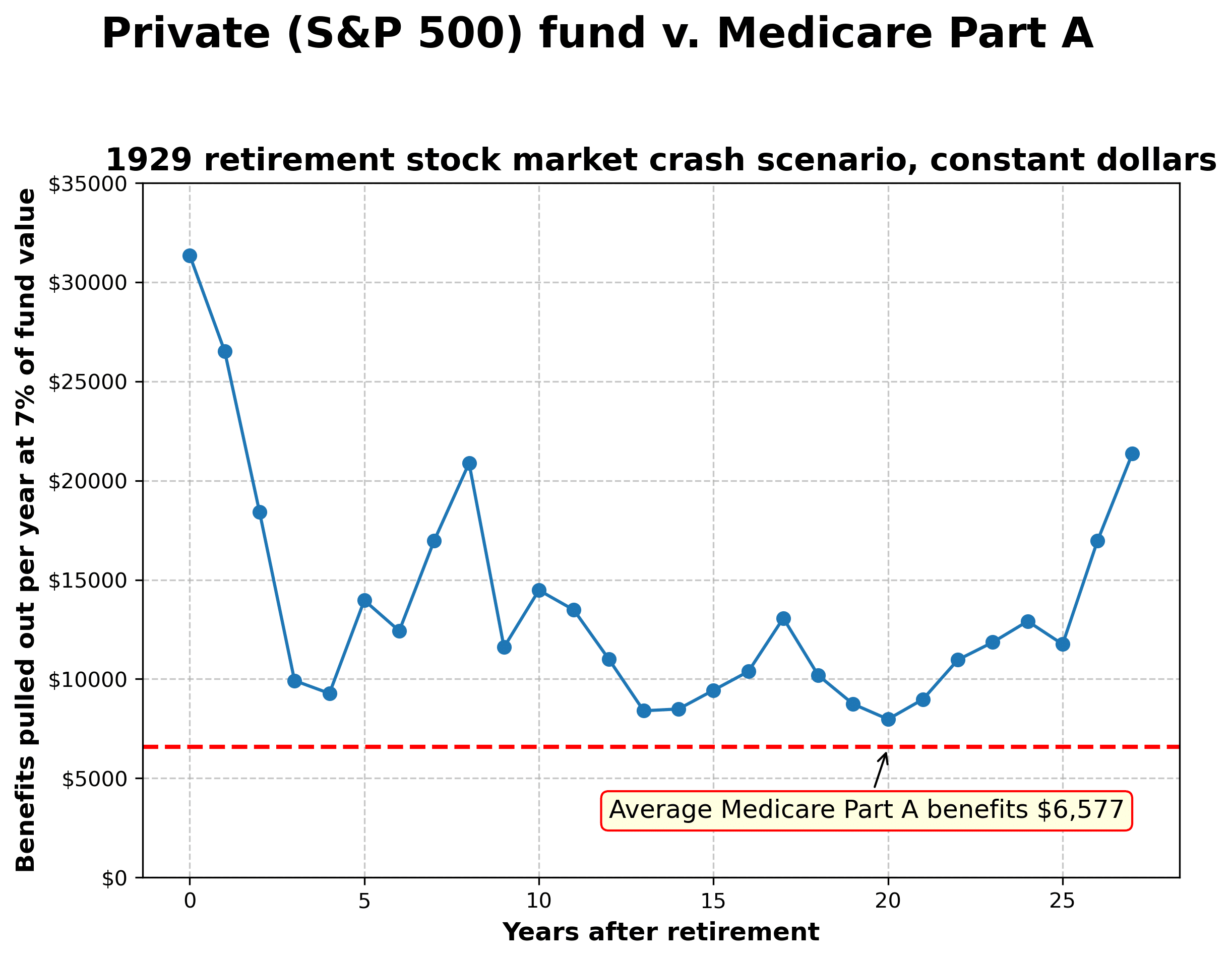

Medicare Part A (the part that’s funded by payroll taxes) spent $394.6 billion in 2024 for the approximately sixty million of the over 65-years-of-age Americans on Medicare Part A (about 11.8% of the total recipients of the sixty-eight million people on Medicare are under 65 years old and generally not part of Medicare Part A). This means Medicare Part A paid out an average of $6,577 for each of its sixty million recipients in 2024.

It’s important to stress that this analysis is designed to evaluate Medicare Part A only, as it is the only part of Medicare the federal government claims is funded directly by worker payroll taxes. Medicare parts B and D are not assessed with this essay (nor is Part C, Medicare Advantage, other than the proportion in which Part A is assessed), as these have been openly welfare programs from the start, and are almost exclusively funded by general government revenues and other sources of revenue. Also, I have posted the spreadsheets used for this article and Python code used to make the two graphs on my blog.

The average American worker retiring in December 2023 paid in more than $42,000 of Medicare (HI) payroll taxes toward the Medicare Part A from the time they first entered the workforce around 1978. If they had instead invested that $42,000 into a Standard & Poors 500 index fund as they earned those wages taxed, less a 0.10% management fee (SPYDER charges 0.09%), they would have accumulated a private fund they personally owned worth more than $447,000. This means they could safely pull out 7%, or more than $31,000 annually, from the fund to buy insurance.

These numbers raise the question: Why can Medicare Part A not be privatized? Average working people could pool their health care money privately and pay for more than four times as much health care as Medicare, and still die with more than $470,000 dollars in the bank. (Double that for two-income married couples!)

$447,000 buys a lot of hospital insurance, especially when invested at interest.

Wall Street is a “casino,” Medicare’s defenders will and do reply, claiming it’s too risky to place worker’s health care in the hands of the gamblers on Wall Street, a sentiment long echoed by politicians in Washington DC.

So let’s take a closer look at this Wall Street casino and do a “crash test” using the 1929 crash as a model. The practical difference between Wall Street and a casino is that we’re dealing with real assets in a stock market that manufacture tangible products people want (from phones to cars) and owning a share of these companies earns investors dividends. The casino has no tangible assets behind it and neither do the bets made at a casino. A gambler could go into a casino and blow the entire $447,000 on a single wager at the roulette wheel by putting all the money on red and the wheel coming up black. And the game is rigged so that the house always wins, and the customers—on net—always lose.

What about risks in the stock market? There’s clearly a big risk in stock investments. The key question is, how much risk?

If you had saved up that $447,000 and every year pulled 7% out of this fund to pay your medical bills—and the market endured a 1929-level meltdown—how long do you think the fund would last?

The answer is it would never run out of money, and it would always pay out more than Medicare.

Surprised?

You shouldn’t be. If you had put $1,000 into the Standard & Poors 500 in January 1929, just before the worst stock market crash in American history, and left it there it would be worth $5,472,698.91 at the end of 2023 ($307,130.09 after adjusting for inflation). That’s what ninety-four years of compound interest gets you, even when you invest at the very worst point in American financial history. And 2024 added 25.02% to that amount.

Most people don’t know this fact, because they’ve never run the numbers. It’s a strange kind of casino when you put all your money down on red, the roulette wheel comes up black, and you still win in the end.

The long-term yield on an S&P 500 investment has always been a bit more than 7%, after adjusting for inflation—even including the Great Depression, the severe bear markets of 1973-74 and 2000-02 and the 2008 financial meltdown.

To put the “crash test” scenario into more context, that 7% pulled out would decrease by more than two-thirds over several years if a person started pulling their full 7% out on the very year of the 1929-style crash, and it would drastically lower the benefit levels for several decades.

But as you can see from the above chart, even Great Depression-level triple-dip stock market crashes wouldn’t lower annual benefits down to the Medicare level. If we assume a magic insurance subscription level at $6,577 per year (the current Medicare Part A annual average expenditure) at 65-years of age and beyond, even after drawing out 7% per year in the 1929 worst-case-scenario, the fund for an average wage earner would never run out of money and would always pay out more for an insurance policy than Medicare Part A pays. (The above chart adjusts all amounts for inflation.)

It’s also important to stress that a 1929-level crash and Great Depression where the unemployment rate remained at about 15% for a decade (with a significant additional proportion being under-employed) would utterly bankrupt the “pay-go” government Medicare system dependent upon ongoing payroll taxes.

But even with the above, this is being far too generous for the accounting of the Medicare fund versus a private fund, at least going forward. The full 2.9% payroll tax wasn’t imposed on working people until 1986, nearly a decade after those retiring in 2023 entered the workforce. Going forward, this is a gross underestimation of the wealth workers would accumulate in an alternative private fund. Investing more money earlier in life makes a huge difference in what comes out in retirement. Calculate for those workers retiring at the end of 2023 if they had instead paid the full 2.9% payroll tax in those early years of their employment and the workers retiring end with a fund worth nearly $600,000.

And let us not forget that a private fund which draws out only 7% annually maintains an asset base of more than $447,000 (or $600,000, going forward) which is retained until death, and can be gifted to a surviving spouse or child for funding health care or any other need. Medicare gives you nothing at death, not even a sympathy card for leaving you broke.

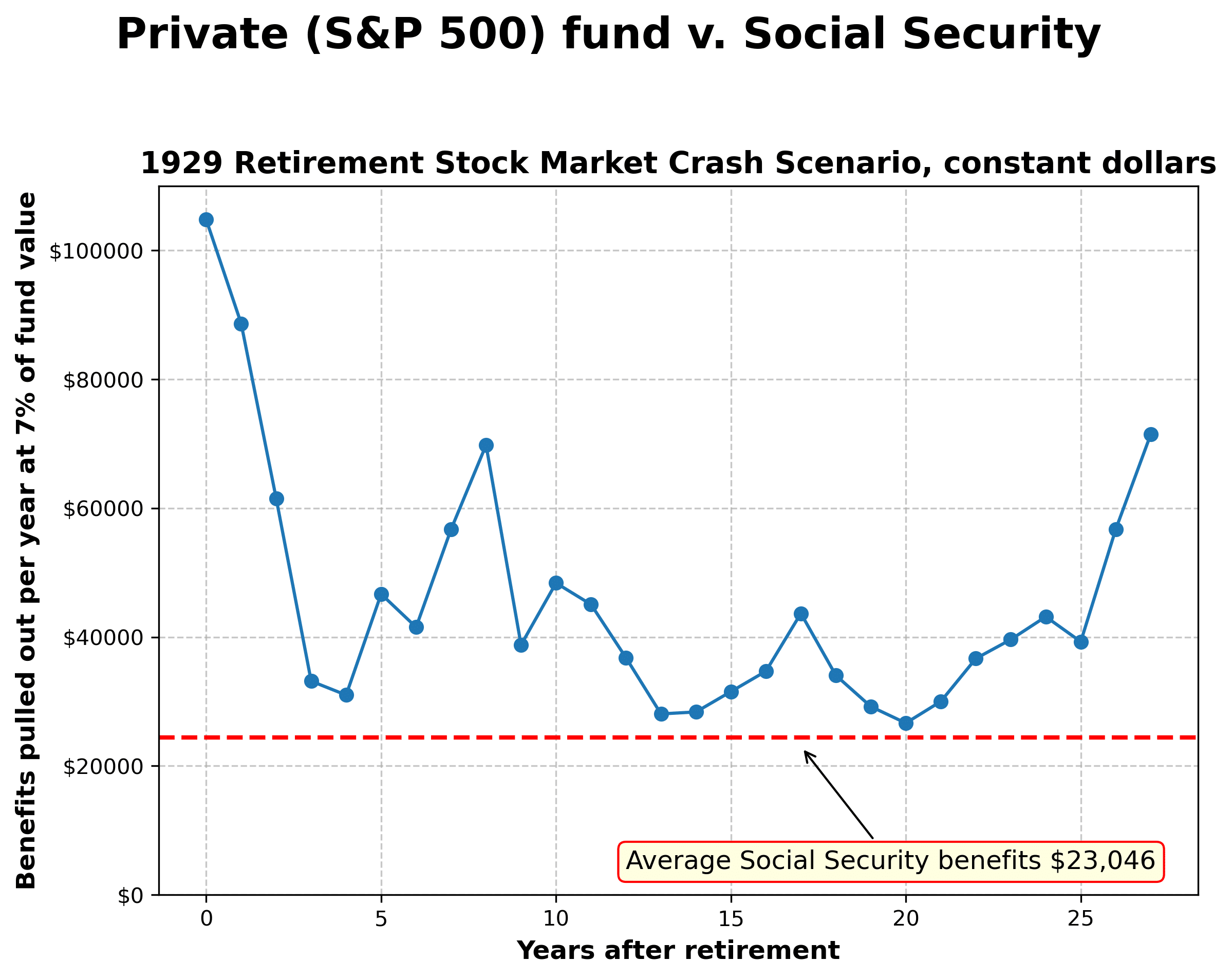

The same math works similarly for Social Security taxes, even under the 1929-level stock market systemic crash.

An average wage-earner retiring on January 1, 2024 would end with a private Social Security fund of more than $1.4 million, assuming the same OASI Social Security 10.4% payroll tax investment in an S&P 500 fund with normal market fees (0.1%/year) and withdrawing funds for a life insurance program (Social Security’s OASI program also includes a “survivors” benefit). That means pulling out 7% is more than $100,000 per year, quadruple the $23,046 paid out by Social Security to the average retired worker. With the real-world S&P 500 yield in 2024 being +25.02%, that would increase the yield to more than $125,000 per year. The theoretical counter-factual, a 1929-level stock market crash retirement scenario in 2024 (charted above), substantially lowers payments after the crash but nevertheless remains lopsided in favor of the private investment fund. Even with the crash of the “Wall Street casino,” a private investment of tax dollars pays out more every year than Social Security, and in close to the same multiples as Medicare Part A compared to the government program.

How bad must Medicare and Social Security be as investments if 100 out of 100 years they’ve both been a worse investment than a casino?

Another objection to the above might be expected along the following lines: “Your numbers for Medicare are no good because the government subsidizes and suppresses the costs of medical care to the elderly through the Medicare program. You’re measuring numbers for below-market-rate health care for the elderly provided through the power of government. The costs of a purely private health care system for the elderly would be higher.”

There’s at least an element of truth to that argument: Government regulations and their massive bargaining power have suppressed the cost of care to the elderly (though in other ways government massively inflates the costs), and as a result health care costs charged to the government are lower for the elderly when compared to the health care costs for everyone else (working age people and children) in the private sector for these same services.

But this is an argument against Medicare and not in favor of it. If children and their working age parents are paying more than their fair share of health care costs, and their funds are being used to subsidize the elderly, as the claim goes, then they could be investing those current overspendings on health care for their own retirement when they may need them.

The current government/private system where the elderly on the government system are subsidized by the young on the private system means that young people should have more money to save and more compound interest for a bigger nest egg at retirement if the system were fully privatized. Paying later is always a better deal when you’re earning compound interest at a rate that outpaces inflation (and even the inflationary rate of health care costs), which the stock market does.

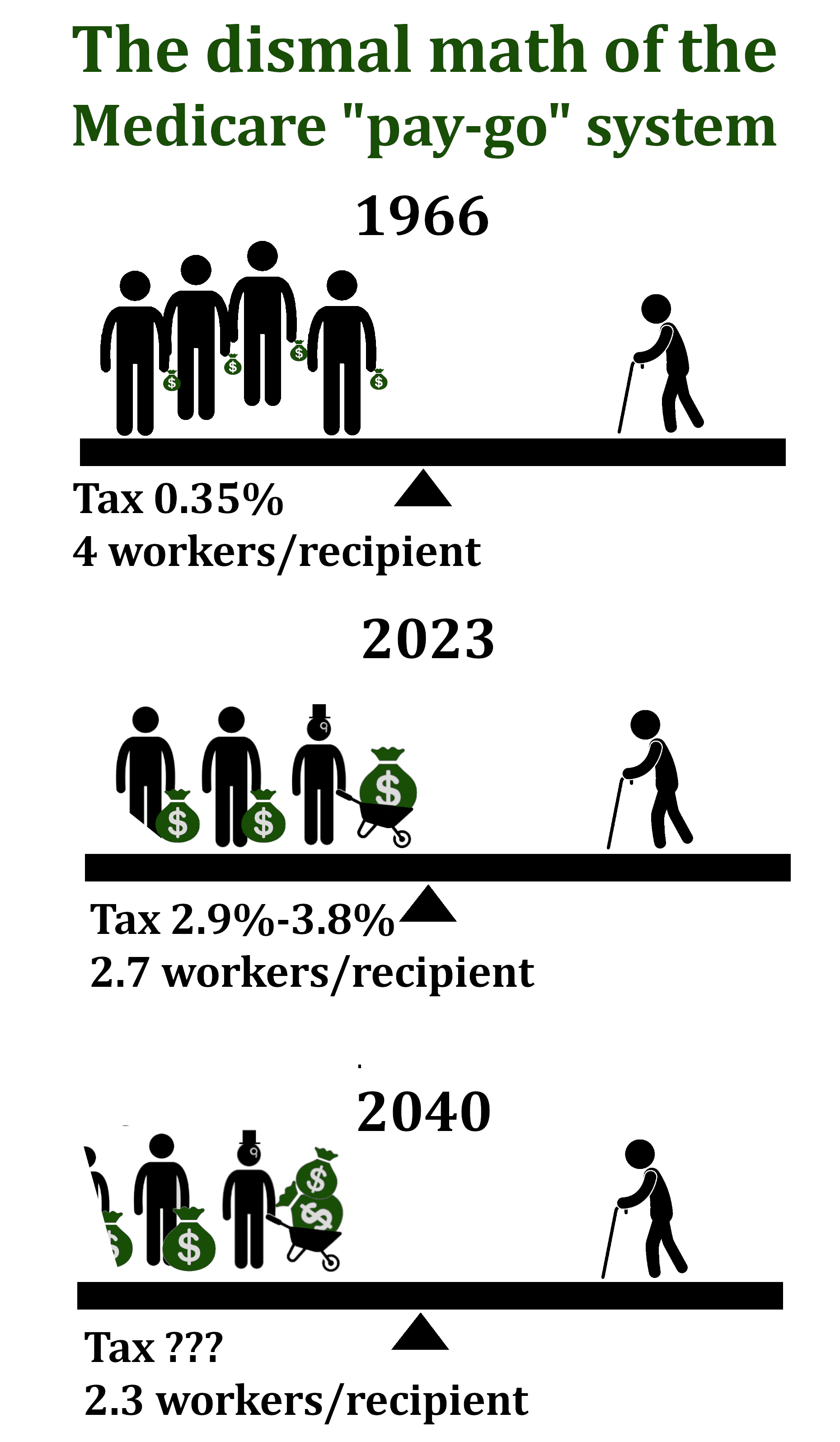

The real casino is the government system, and it’s a deliberately crooked casino run by wealthy Mafia-style barons in Congress and the Federal Reserve Bank. To prevent Medicare running a deficit every year, new taxes on both poor and middle class workers as well as special taxes on rich people have constantly been added to subsidize the failing program in order to prevent it from running a deficit. The Medicare payroll tax rate on poor and middle class workers has already increased 729% since 1966 (and much more for rich people). Yet, despite these many tax increases over the years, the trustees of the Medicare Trust Fund predict it will run a deficit again by 2030. And the Medicare Trust Fund trustees estimate the entire trust fund will be depleted in fiscal 2036. Probably sooner, because the Federal Reserve Bank is currently robbing the trust funds by artificially suppressing Treasury bill interest rates, which Medicare and Social Security trust funds rely upon to keep up with inflation (and for the last four years, they haven’t).

Saying “we should trust the government program” while the government is actively and by deliberate policy robbing the program’s trust fund through inflation and interest rate manipulation is peak cognitive dissonance.

And like a casino, the Medicare program will not have any assets after 2036 on which to draw for benefits.

The numbers above demonstrate that Medicare’s existence for the average American is already a worse investment than putting their medical insurance in the market at the peak before the 1929 crash. Anyone could run those numbers, but Washington and the politicians selling the programs will never will do it for you.

There’s worse news for Medicare. The unavoidably dismal math of the program necessitates it will get perpetually worse, because Medicare (like Social Security) basically relies upon a “pay-go” system where three current workers pay $2,000 each per year in order for one elderly patient to receive his 14 years of retirement benefits at $6,000 per year.

Older people are living longer, and collecting benefits longer, and that trend will likely continue into the future. When Medicare started doling out benefits in 1966, life expectancy was just over 70. So people collected benefits for only a little over five years. Today, life expectancy is about 79, meaning people are pulling benefits nearly three times as long. By 2040, the Social Security Administration estimates life expectancy will be 80.5 years, and the Medicare and Social Security trustees estimate there will be only 2.3 workers for every person receiving benefits.

For an extreme demonstration of the mathematical nightmare the Medicare and Social Security pay-go systems suffer under a scenario of longer lifespans, consider the possibility that the average person’s life could be extended to 200 years, with the same annual cost of medical care for those over 65 today. How would it be possible for people working from 18-65 to support everyone living off the pay-go system from ages 65-200? It would require one worker to support three people on Medicare under such a scenario, rather than the three workers supporting a single retiree today. Taxes would have to be increased on workers nine-fold just to maintain the same benefit levels. While this is an extreme example, the general trend is moving slowly and inexorably toward that direction.

If an elderly person is under a private system with accumulated capital like that described in the S&P 500 private fund scenario, longevity doesn’t matter. The fund can provide 7% benefits forever because the fund is paid out of the perpetual profit from the investments. That person who could have retired in 1929 with his fund worth $447,000 in today’s dollars would be pulling out that 7% annual benefit that was $15,800 last year, ninety-four years later, even with that initial four-year crash and three subsequent stock market crashes.

But if a patient continues to live longer on the government Medicare program, the system runs a deficit and politicians face the choice of raising taxes on working people (who will receive the same low benefit levels) or cutting benefits for the elderly even further. Congress has chosen the first option many times since 1966. It’s just simple math that this program will only become a worse deal financially for workers as people live longer, draw more total benefits over time and the baby bust continues.

In the end, there are those who support continuing Medicare and Social Security as is, and those who do math. And the people supporting Medicare are like those cheering enthusiastically in the casino when those penny slot machine speakers joyfully blast out “Winner!” and all the lights and bells go off to tell them that they “won” $1.75 back from their three dollar bet.

Government-provided health care (and government-provided retirement income) can never be as efficient as the private sector in delivering services. If Medicare (and Social Security) were really enacted to provide more income and security for ordinary working people, the programs would already be in the act of being privatized. But socialists don’t do math, and government officials never miss a chance to broadcast “Winner!” to voters and highlight the $1.75 while doing their best to obscure the three-dollar bet you made to get those “winnings.” Government health care only provides a “service” of impoverishing the middle class while at the same time restricting the freedom of choice of what ordinary people can do with their own money, not to mention limiting their financial independence.

Don’t let the socialist 1929 “crash test dummies” who can’t (or won’t) do math convince you that Medicare and Social Security make financial sense!