Today in history, on August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon slammed shut the “gold window” and eliminated the last vestige of the gold standard.

Nixon ordered Treasury Secretary John Connally to uncouple gold from its fixed $35 price and suspended the ability of foreign banks to directly exchange dollars for gold. During a national television address, Nixon promised the action would be temporary in order to “defend the dollar against the speculators,” but this turned out to be a lie. The president’s move permanently and completely severed the dollar from gold and turned it into a pure fiat currency.

Nixon’s order was the end of a path off the gold standard that started during President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration. June 5, 1933, marked the beginning of a slow death of the dollar when Congress enacted a joint resolution erasing the right of creditors in the United States to demand payment in gold. The move was the culmination of other actions taken by Roosevelt that year.

In March 1933, the president prohibited banks from paying out or exporting gold, and in April of that same year, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6102. It was touted as a measure to stop hoarding, but was, in reality, a massive confiscation scheme. The order required private citizens, partnerships, associations and corporations to turn in all but small amounts of gold to the Federal Reserve at an exchange rate of $20.67 per ounce. In 1934, the government’s fixed price for gold was increased to $35 per ounce. This effectively increased the value of gold on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet by 69 percent.

The reason behind Roosevelt’s executive order and the congressional joint resolution was to remove constraints on inflating the money supply. The Federal Reserve Act required all Federal Reserve notes have 40 percent gold backing. But the Fed was low on gold and up against the limit. By increasing its gold stores through the confiscation of private gold holdings, and declaring a higher exchange rate, the Fed could circulate more notes.

While American citizens were legally prohibited from redeeming dollars for gold, foreign governments maintained that privilege. In the 1960s, the Federal Reserve initiated an inflationary monetary policy to help monetize massive government spending for the Vietnam War and Pres. Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society.” With the dollar losing value due to these inflationary policies, foreign governments began to redeem dollars for gold.

This is exactly how a gold standard is supposed to work. It puts limits on the amount the money supply can grow and constrains the government’s ability to spend. If the government “prints” too much money, other countries will begin to redeem the devaluing currency for gold. This is what was happening in the 1960s. As gold flowed out of the U.S. Treasury, concern grew that the country’s gold holdings could be completely depleted.

Instead of insisting on fiscal and monetary discipline, Nixon simply severed the dollar from its last ties to gold, allowing the central bank to inflate the money supply without restraint.

When he announced the closing of the gold window, Nixon said, “Let me lay to rest the bugaboo of what is called devaluation,” and promised, “your dollar will be worth just as much as it is today.”

This was also a lie.

According to the Consumer Price Index data released by the Bureau Labor of Statistics, the dollar has lost more than 80 percent of its value since Nixon’s fateful decision. Meanwhile, the dollar value of gold has gone from $35 an ounce to about $1,500.

As Nick Giambruno put it in an article published by the International Man, “This is all a predictable consequence of the U.S. abandoning sound money.”

By every measure—including stagnating wages and rising costs—things have been going downhill for the American middle class since the early 1970s. August 15, 1971, to be exact. This is the date President Nixon killed the last remnants of the gold standard. Since then, the dollar has been a pure fiat currency. This allows the Fed to print as many dollars as it pleases. And—without the discipline imposed by some form of a gold standard—it does precisely that. The U.S money supply has exploded 2,106 percent higher since 1971. The rejection of sound money is the primary reason inflation has eaten up wage growth since the early 1970s—and the primary reason the cost of living has exploded.”

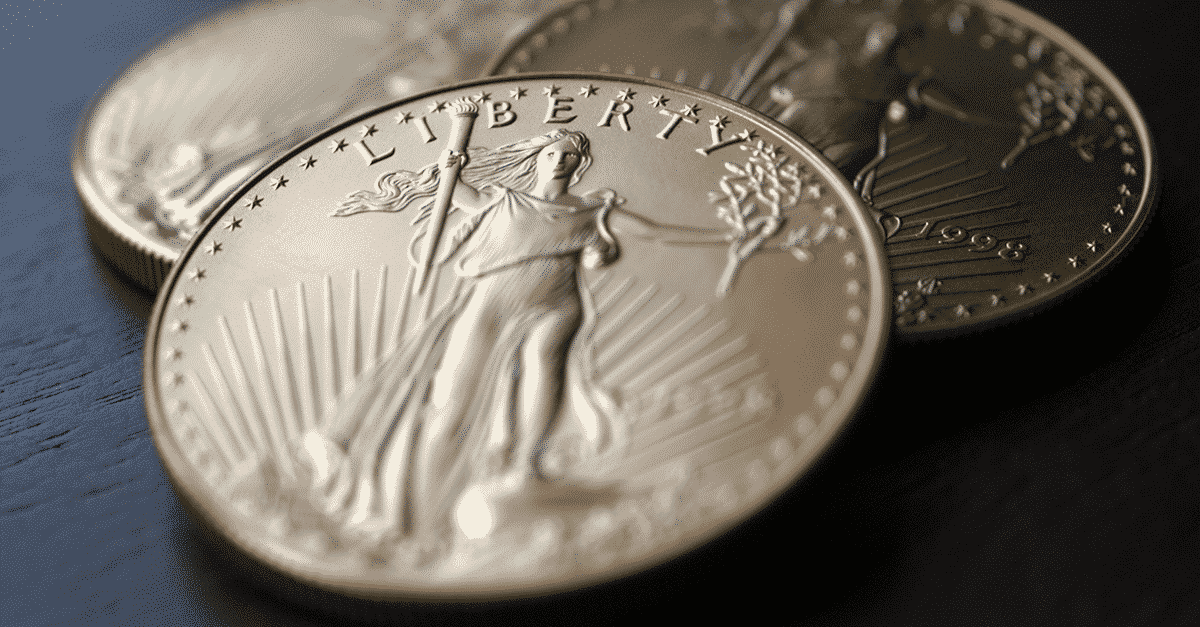

Practically speaking, this means that if you stashed an ounce of gold worth $35 alongside thirty-five one-dollar bills under your bed in 1971. Today, you would be sitting on gold that would buy you an expensive tailored suit. The $35 in cash couldn’t get you a pack of fancy boxer shorts.

In a 2017 article, financial guru Jim Grant explained the importance of a gold standard and how it restrains the power of government.

What was the gold standard, exactly — this thing that the professors dismiss so airily today? A self-respecting member of the community of gold-standard nations defined its money as a weight of bullion. It allowed gold to enter and leave the country freely. It exchanged bank notes to gold, and vice versa, at a fixed and inviolable rate. The people, not the authorities, decided which form of money was best.

“The gold standard was a hard task master, all right. You couldn’t devalue your way out of trouble. You couldn’t run up a big domestic budget deficit. The central bank of a gold-standard country (if there was a central bank) was charged with preserving the convertibility of the currency and, in a pinch, serving as lender of last resort to needy commercial banks. Growth, employment and price stability took their own course. And if, in a financial panic or a business-cycle downturn, gold fled the country, it was the duty of the central bank to establish a rate of interest that called the metal home. In the throes of a crisis, interest rates would likely go up, not down.”

Grant wrote that the reason the gold standard is so often demeaned by modern economists and politicians is because, “The modern sensibility quakes at the rigor of such a system.”

In effect, the gold standard replaced by another standard. Grant calls it the “Ph.D. standard,” a system run by politicians and central planners.

That system features monetary oversight by former university economics faculty — the Ph.D. standard, let’s call it. The ex-professors buy bonds with money they whistle into existence (“quantitative easing”), tinker with interest rates, and give speeches about their intentions to buy bonds and tinker with interest rates (“forward guidance”).

This is exactly what politicians like Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, Bush I, Clinton, Bush II, Obama and Trump wanted — the ability to spend without restraint and grow government with no limits. The result: massive national debt and devalued currency that buys the average person less and less every year.

As Ryan McMaken summed up in an article on the Mises Wire:

Nixon yearned to be free of this restraint so he could spend dollars more freely, and not have to worry about their value in gold. Nixon’s move was, in short, the final and total politicization on money itself, and, as Grant notes, ‘The Ph.D. standard is … a political institution. It is the financial counterpart to the philosophy of statism.’