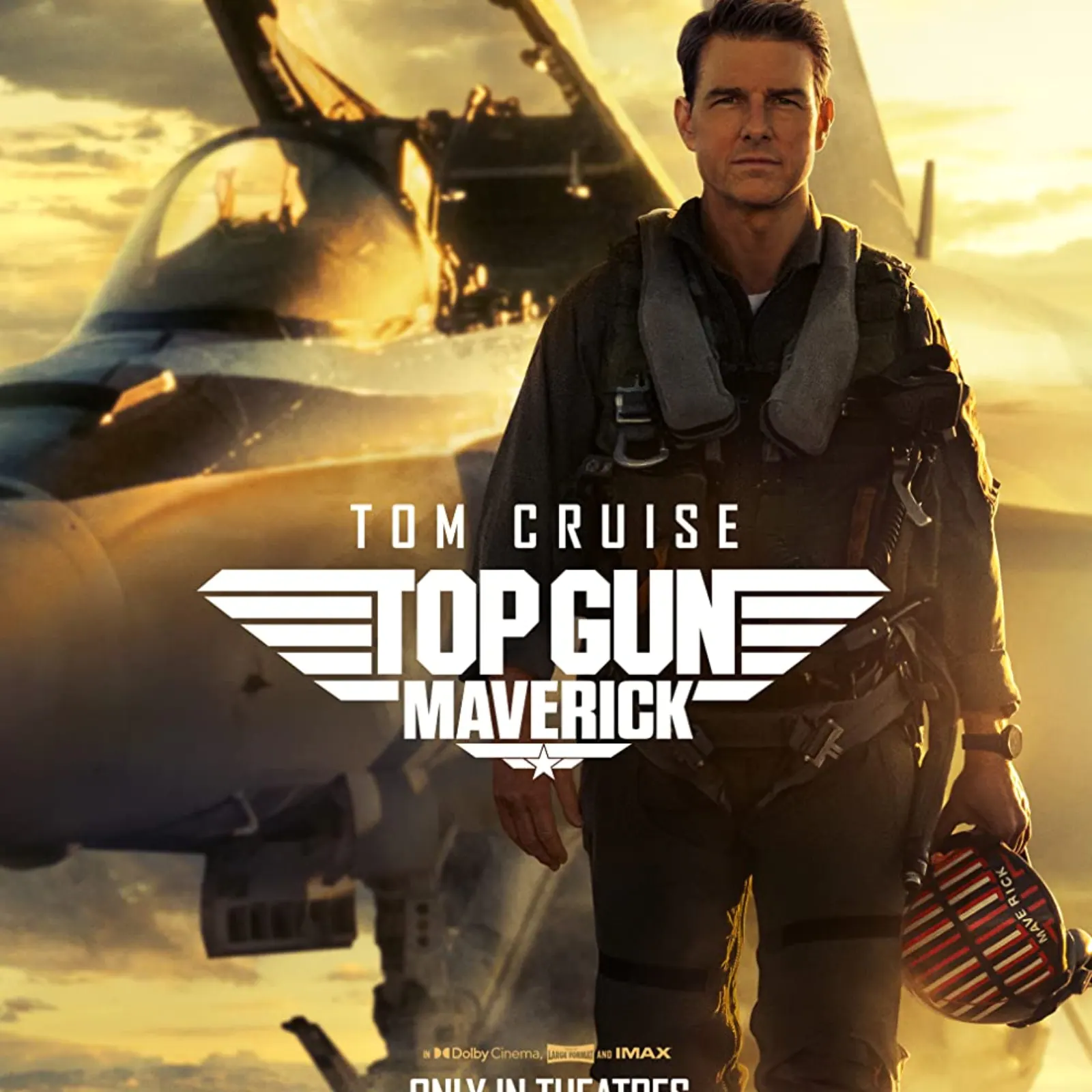

Top Gun: Maverick is a brilliant film. Any film that can elicit the praise of Ben Shapiro, Willie Geist and Russell Brand, receive a five-minute standing ovation at the Cannes Film Festival and make over $1 billion is, as the Stalinists would say, “objectively” brilliant. Moviegoers and film critics are loving it.

Unfortunately, for those of us opposed to militarism, empire and genocide, Top Gun: Maverick is not just a fun summer sequel to 1986’s Top Gun. It is also a preeminent cultural product of participatory fascism.

Participatory Fascism

Robert Higgs popularized the concept of participatory fascism in his book, Crisis and Leviathan.

Higgs wrote in 2012:

“For thirty years or so, I have used the term “participatory fascism,” which I borrowed from my old friend and former Ph.D. student Charlotte Twight. This is a descriptively precise term in that it recognizes the fascistic organization of resource ownership and control in our system, despite the preservation of nominal private ownership…”

In Crisis and Leviathan, Higgs argued that corporate America had become “half master, half slave” to the National Government:

“As Charlotte Twight has shown, the essence of fascism is nationalistic collectivism, the affirmation that the ‘national interest’ should take precedence over the rights of individuals.”

Hollywood’s Subservient Fascist Participation

Hollywood promotes nationalistic collectivism with the full cooperation of the U.S. government. In their book National Security Cinema, Matthew Alford and Tom Secker wrote:

“For over a century, filmmakers in America have received production assistance in the form of men, advice, locations, and equipment from the US military to cut costs and create authentic-seeming films.”

Top Gun: Maverick received invaluable assistance from the Pentagon. According to U.S. Air Force Major General Edward Thomas, the military had an agenda: recruitment.

In an interview with Geist, Thomas said:

“Back in 1986, Top Gun got a whole generation excited about Naval aviation. Excited about coming and doing military flying and joining the service. And our hope is that as people go and see this movie…that they’ll get excited all over again about flying for the U.S. Military.”

While 1977’s Star Wars: A New Hope did function as an uplifting nationalistic collectivist film, George Lucas intended it to serve as an anti-imperial story, particularly when most appropriately viewed as part of a six-film epic. This reading of the film has proved more enduring. No one talks about Luke Skywalker boosting military recruitment. Top Gun: Maverick, meanwhile, was dreamt up by Hollywood and the Pentagon to boost the ranks.

A Deceptive Narrative

Top Gun: Maverick represents the Navy and its personnel in a glowing light.

As Shapiro puts it:

“It’s very patriotic, the film. It’s just…the military is a bunch of good-looking young people who are going out to defend the country under the riskiest of circumstances and doing crazy things to defend their country and the international order. That’s awesome. That’s good stuff.” [Emphasis added]

That’s misleading stuff. When you hear “international order,” think empire. And recognize what the film doesn’t show;

- The think tanks that dreamt up the policy of “containing” the enemy nation.

- The American state, domestic weapons manufacturers and foreign governments that funded those think tanks.

- The U.S. generals and spymasters who aspire to work for one of those weapons companies or foreign governments.

- The president who makes war decisions under threat of a constant existential crisis: the crisis that he might not get re-elected and/or be deified by historians.

Top Gun: Maverick takes place in a world in which the most powerful military is rationally deployed to protect Americans. Sadly, that’s not the world we live in.

Hollywood as Master

Participatory fascism is destructive, but it’s a lot better than communism. Hollywood is government affiliated, but it’s not a government run industry. Top Gun: Maverick wasn’t exclusively created to boost military recruitment. It’s also supposed to make money.

In his review of the film, Brand said, “Loads of you would just say it’s a bloody good film. And of course it is.”

Top Gun: Maverick had to appeal to a broad audience to achieve its success. This necessity tamped down potentially divisive demagoguery. It is pro-military, but it isn’t anti-market. It certainly isn’t pro-market; most of the main characters are government employees. It just doesn’t attack the market. The third act mission isn’t to blow up an evil corporation. The film isn’t woke but it isn’t anti-woke either. And it can be interpreted as a metaphor for Hollywood’s favorite topic: Hollywood itself and the art of filmmaking.

Now consider what Johannes Schönherr wrote in his book, North Korean Cinema: A History:

“Like many other ideological dictatorships of the 20th century, North Korea has always considered cinema to be an indispensable propaganda tool. No other medium was as powerful as the movies; no other medium could penetrate the whole population even in the remote corners of the country so thoroughly and so effectively. In addition, no other medium was right from the founding of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (to give the official name of the state) so strictly and so exclusively under state control.”

North Korea’s most critically acclaimed film, 1972’s The Flower Girl, is relentlessly anti-market and pro-government. In 1978, the North Korean government abducted South Korea’s most revered director, Shin Sang Ok, and forced him to make films for the regime. And every filmmaker in North Korea knows that if they offend the Dear Leader, they’ll be imprisoned, tortured, or shot.

Thus, Top Gun: Maverick simultaneously represents much that is wrong but also a little bit that is impressive about our economic-social-cultural-political order. Its story might be participatory propaganda, but its existence and financial success highlights the power of peaceful market interactions.

If viewing Top Gun: Maverick has you thinking about enlisting in the United States Military, consider attending acting school instead. You’re better off playing soldier in the movies.