The Assassination of President Jovenel Moïse

During the early morning hours of Wednesday, July 7, 2021, Haitian President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated in his home by a team of gunmen. His first lady, Martin Moïse, was critically injured. She was airlifted to Florida for treatment where she remains in critical condition.

Moïse was elected president of Haiti on February 7, 2017. According to Moïse’s opposition, his four-year term was to end on February 7, 2021. Moïse refused to step down on that date, arguing the Haitian constitution entitled him a five-year term. He has since remained in office, spurring months of opposition protests and rising crime rates that some outlets blame on Moïse himself.

The aftermath of the assassination was filmed by the late president’s neighbors. According to the Maimi Herald, a man can be heard in one of the videos yelling in English over a megaphone: “DEA operation. Everybody stand down. DEA operation. Everybody back up, stand down.”

Bocchit Edmond, the Haitian ambassador to the U.S., stated the attack “was carried out by foreign mercenaries and professional killers,” that it was “well-orchestrated,” and that the attackers were “masquerading as agents of the DEA.” He asked the U.S. government for assistance with the investigation.

Haitian officials claim at least twenty-eight people were involved in the assassination plot including twenty-six Colombian citizens and two Haitian-Americans. On July 8, Haitian national police chief Leon Charles confirmed that fifteen Colombians and the two Haitian Americans had been taken into custody. Three others were killed in a firefight with authorities. The two Haitian-Americans were identified as thirty-five-year-old James Solages and fifty-five-year-old Joseph Vincent.

Solages has been circumstantially linked to Haitian oligarchs Reginald Boulos and Dimitri Vorbe. Although Boulos and Vorbe were initially friendly to Moïse, they later became his outspoken critics, leading many Haitians to believe they are involved with the killing.

The day before the assassination, president Moïse nominated Ariel Henry, a neurosurgeon, to replace Joseph as prime minister. Henry was slated to be sworn in to the position on the afternoon of the killing, Wednesday, July 7. Following the assassination, Moïse’s interim prime minister, Claude Joseph, assumed a tenuous control of the Haitian government over Ariel Henry. As of the writing of this article, Joseph remains in power, though questions persist regarding the proper succession of presidential authority.

Joseph declared a state of martial law immediately following news of the assassination. Fearing unrest, the Dominican Republic closed its border with Haiti and the Port-au-Prince-Toussaint Louverture International Airport was shuttered, with all arriving planes being rerouted.

Despite Joseph’s declaration of martial law, the political situation appears relatively stable, at least for the moment. Nonetheless, the assassination has the potential to exacerbate an already turbulent political state of affairs—one to which the U.S. and other international influences not innocent third parties.

The U.S. and the O.A.S. Have Controlled the Haitian Presidency Since at Least 2011

If the current Haitian political arrangement appears chaotic, the U.S. and the U.S.-led Organization of American States (“O.A.S.”) own a lion’s share of the blame:

In April, 2009, the [U.S.] State Department, under the leadership of Hillary Clinton, decided to completely change the nature of the U.S. cooperation with Haiti.

Apparently tired with the lack of concrete results of U.S. aid, Hillary decided to align the policies of the State Department with the “smart power” doctrine proposed by the Clinton Foundation. From that moment on, following trends in philanthropy, the solutions of U.S. assistance would be based solely on “evidence.” The idea, according to Cheryl Mills, Clinton’s chief of staff, “was that if we’re putting in the assistance, we need to know what the outcomes are going to be.”

The January 2010 earthquake was the long awaited opportunity to test this new policy.

The idea was to transform Haiti into a Taiwan of the Caribbean, with maquiladoras, an apparel industry, tourism, and call centers. These would be the niche sectors that would guide the new cooperation framework.

In this plan, the particularities of Haiti itself didn’t matter much.

To set this plan in motion, Clinton selected Cheryl Mills to head the U.S. State Department’s Haiti Task force despite the fact that Mills had neither training nor experience in international development.

In order for the Haitian People to accept Clinton and Mills’ technocratic agenda, it had to be window dressed as democratic consensus. This first required the breaking of the country’s deadlocked presidential race, which had been pushed from April 28, 2010 to November 28, 2010 in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake. After the November vote, the election became deadlocked when none of the candidates received the required 50 percent of the vote.

According to the Haitian election commission, the candidates who received the two highest November vote totals were Mirlande Manigat, a former first lady, and Jude Célestin, the candidate backed by the then-outgoing president, René Préval. The two candidates were scheduled to compete in a final run-off election March 28, 2011.

Despite the Haitian election commission’s findings, Clinton and the O.A.S. conducted their own audit of the November vote totals. This audit found popular Haitian singer Michael “Sweet Micky” Martelly had actually placed second and not Célestin. Incidentally, Martelly was the preferred candidate of the O.A.S.

To assure the Haitian people did not make the wrong choice, Hillary Clinton met with then-outgoing president René Préval on January 30, 2011. In this meeting, Clinton muscled Préval into breaking the electoral stalemate between the front running candidates:

Towards the end of the meeting, she asked Préval to make a last gesture in favor of harmony and understanding. It was to be a gesture that would lead him, once and for all, to a special place in the pantheon of Haiti’s history and the struggle for democracy in the continent. Préval replied with an emotive, albeit enigmatic smile. It was only him who knew that the crisis had reached its epilogue at that moment.

As she was leaving the house, Hillary invited Bellerive to accompany her. The [then-]prime minister asked Préval for authorization to do so and placed himself between the two women inside the armored truck that left in a convoy to the airport. Confident that she had obtained what she wanted, Hillary was concerned now with the result of the second round. Bellerive removed all traces of apprehension when he informed her that Michel Martelly was going to win easily. And so he did.

As she was heading toward the plane, Hillary made a comment to Bellerive about his family relationship with Martelly. He confirmed that they were distant cousins. Since they were both educated individuals and the game was already over, the secretary of state allowed herself to make a joke and asked: “You are relatives, but you don’t sing?” Bellerive replied, humorously: “Neither does he.”

Hillary confessed having heard Martelly sing some songs and could not agree more with Bellerive. Then, smiling, she left Haiti.

Martelly proved to be a heavy-handed leader who was subservient to international interests. During his presidency, NGOs and the U.S. State Department poured 12.9 billion dollars into Haiti (ironically, under the slogan “Building Back Better”). One central planner in the U.S. State Department’s Haiti Task Force called the program a “Petrie dish” for technocratic central planning.

Despite the investment, Haiti remained in an appalling state of ruin, raising questions of how exactly that money was used.

In 2015, Martelly’s term expired and elections were again delayed. Eventually, Moïse, Martelley’s hand-picked successor, won the presidency. Several observers deemed this election provably fraudulent, pointing to undue influence from E.U. and O.A.S. observers. The fraud allegations became so prevalent that the Haitian electoral commission formally called for the election’s annulment. Nevertheless, the U.S. and O.A.S. supported the results, leading directly to Moïse’s presidency.

Under the platform “Haiti is Open for Business,” among other efforts, the presidencies of Martelly and Moïse propped the door open for foreign states and N.G.O.s to pillage that country. Furthermore, the presidents also demonstrated a willingness to cooperate with O.A.S.’ meddlesome plans for other Central and South American Nations.

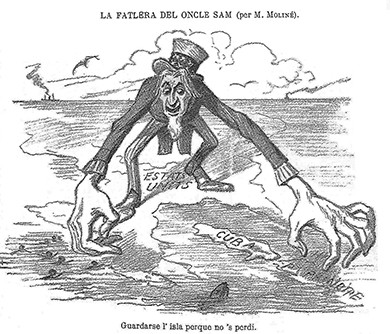

The U.S. Has an Extensive Record of Intervention in Haiti

Indeed, U.S. intervention in Haiti is nothing new. Most notably, the last time a Haitian president was assassinated, the U.S. invaded that country and occupied it for the next nineteen years.

The extended record of U.S. meddling in Haiti is voluminous, as retold by Ted Snider:

America and its allies have a long history of coups and interference that have caused Haiti to struggle to attain stability. Haiti’s democratic wishes have long been snuffed out by the U.S., and the people of Haiti have never had much say in whom they want to lead their country. In 1959, when a small group of Haitians tried to overthrow the savage U.S. backed dictator “Papa Doc” Duvalier, the U.S. military, which was in Haiti to train Duvalier’s brutal forces, not only helped locate the rebels but took part in the fighting that squashed them.

A quarter of a century later, when the people of Haiti longed to elect Jean-Bertrand Aristide to power, the C.I.A., with the authorization of President Reagan, funded candidates to oppose him, according to William Blum in Killing Hope. When the people of Haiti surmounted American obstructions and elected Aristide, the U.S., sometimes with the help of Canada and France, took him out: twice!

C.I.A. expert John Prados says that the “chief thug” amongst the groups of thugs and militia behind the coup was a C.I.A. asset. Tim Weiner, the author of Legacy of Ashes: The History of the C.I.A., agrees. Weiner says that several of the leaders of the junta that took out Aristide “had been on the C.I.A.’s payroll for years.”

More Foreign Intervention Will Not Fix the Errors of Past Foreign Intervention

After the assassination, it took only thirteen hours for the editorial board of the Washington Post to clamor for the U.S., other foreign states, and international NGOs to swoop in with “[s]wift and muscular intervention.” Others, like Colombian president Ivan Duque have also urged for military intervention.

Despite the fact that Moïse’s presidency itself was due in large part to U.S. meddling, the Washington Post laments his poor track record, using it to support its case for more intervention.

The prime directive of said intervention, according to the Washington Post, would be yet another round of elections to “produce a government that would be seen as legitimate in the eyes of most Haitians.” If this new round of elections is anything like the last three, the same international interests will ram through yet another authoritarian lapdog.

To achieve these elections, the Washington Post advocates yet another international peacekeeping force occupy Haiti, much like the 2004-2017 U.N. Stabilization Mission. This is an occupation they conceded introduced a cholera epidemic to Haiti, received many “credible allegations of rape and sexual abuse,” and “fathered hundreds of babies born to impoverished local women and girls.”

You see, the Washington Post argues, the problem is not that nation-building does not work. Instead, the problem with the last U.N. Stabilization Mission was that it constituted troops from Nepal, Brazil, and Uruguay—not from other western leaders. Furthermore, the Washington Post argues the above unintended consequences were worth it, because the “U.N. force did manage to bring a modicum (emphasis added) of stability to the 2004 uprising.”

Of course, the Washington Post fails to mention the U.S.’ instrumental role in causing the 2004 uprising that to begin with.

The ostensible solution to the above unintended consequences is to commit U.N. soldiers from other member countries like the U.S., France, Canada, and additional O.A.S. member states. This proposed U.S. led occupation comes as the Biden Administration is failing to deliver a complete U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, a country the U.S. and other western countries have unsuccessfully occupied for the last two decades, to disastrous effect.

Circumstantial Evidence of U.S. Involvement in the Assassination

Given the Washington Post’s deep ties to the C.I.A., its “editorial board’s” urgent advocacy for U.S. intervention is suspicious. Especially as circumstantial evidence points to some degree of U.S. State Department involvement in the assassination.

For instance, cables released by Wikileaks have linked prime minister Claude Joseph with the National Endowment for Democracy, the U.S. State Department’s engine for regime change operations across the world. Furthermore, the U.S. military has a long history of training and arming the Colombian military, whose veterans composed the majority of the Assassination squad. At least one prominent member of the team, Manuel Antonio Grosso Guarín received direct training from the U.S. Military.

The U.S. State Department has vehemently denied involvement.

Suspicions of U.S. involvement aside, it is infinitely plausible that a very unpopular president was assassinated by purely domestic opposition.

U.S. and U.N. Intervention is Not Warranted Even If Haitian Officials Request It

On Saturday, interim Prime minister Claude Joseph asked the U.S. and U.N. to “deploy troops to protect key infrastructure” to aid the country as it prepares for elections. Mathias Pierre, Haiti’s elections minister, expressed support for Joseph’s request.

On Saturday “a senior Biden administration official said the U.S. has no plans to provide military assistance at this time.” However, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki also noted that agents from the U.S. domestic Federal Bureau of Investigation and Department of Homeland Security would be dispatched to Port-au-Prince “as soon as possible.” Secretary of State Antony Blinken and President Biden have both reportedly “promised to help Haiti.”

Even if Haitian officials ask for assistance, the U.S. and U.N. should not provide it.

If a U.S. business magnate had orchestrated an assassination of the U.S. president and the vice president requested foreign soldiers to secure key infrastructure across the U.S., Americans would likely see these foreigners as an occupying army. In fact, foreign occupation was a large reason the U.S. colonists fought their war for independence. Many American officials at that time had also asked for British occupation.

Many Haitians are equally tired of foreign intervention in their domestic affairs. Journalist Kim Ives, Editor of the English Section of the newspaper Haiti Liberte, told Dan Cohen of Behind the Headlines:

Essentially, we have a U.S. Puppet [Claude Joseph] asking his puppeteer to invade Haiti for the fourth time in just over a century…But in both the region and, above all, the Haitian people are sick and tired of U.S. military interventions, which are largely responsible for the nation’s current debilitated, critical state both economically and politically. Much of the most oppressed neighborhoods are now heavily armed and have already announced a revolution similar to that which emerged against the U.S. marines in 1915 and U.N. ‘peace-keepers’ in 2004, only more ferocious.

Regardless of the outcome of the latest interventionist snafu in Haiti, and regardless of how bad the situation becomes, foreign intervention will not solve the myriad problems caused by foreign intervention. After over a century of ill-fated international involvement in Haiti, it is high time for a radical concept: that Haiti should be left for Haitians to govern themselves.