In his farewell address, George Washington said, “It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.”

What an offensive notion to Pentagon generals, weapon industry execs, DC think tankers and State Department bureaucrats, who, rather than avoiding permanent alliances, have been relentless in their quest to pile on new ones.

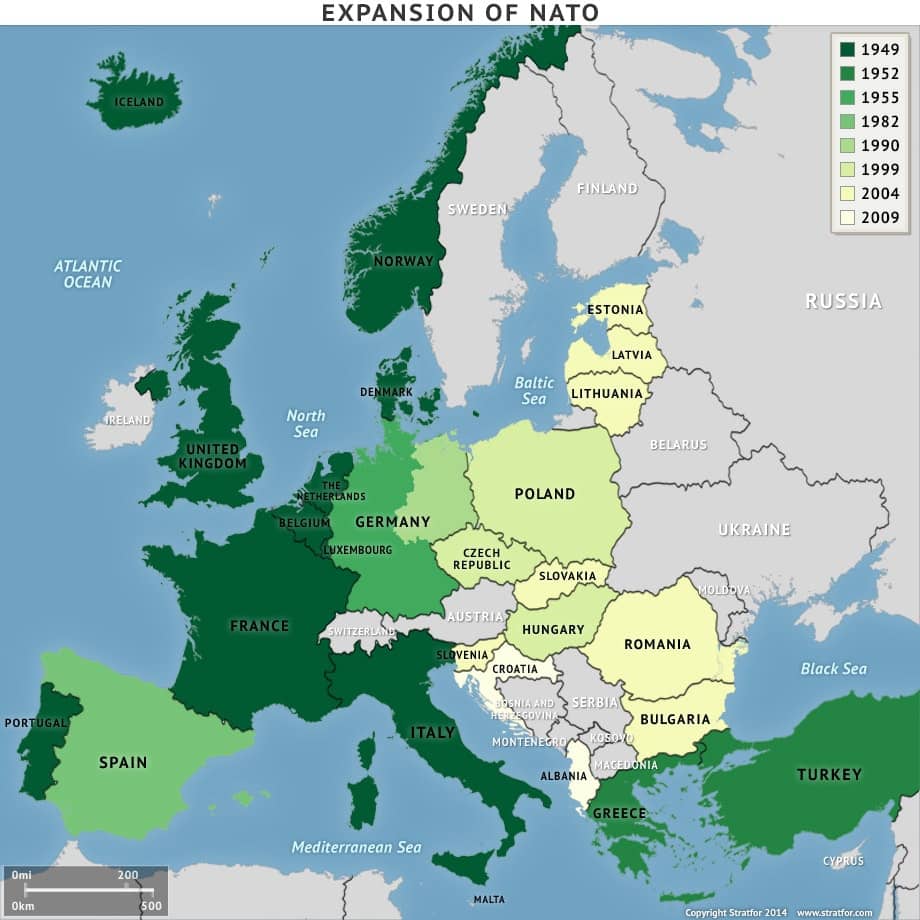

That impulse is vividly exemplified by the dangerously provocative post-Cold War expansion of NATO, and its consequences are apparent in today’s Ukraine-centered tensions with Russia.

NATO was created to oppose a Soviet empire that no longer exists. Had American presidents followed Washington’s sage counsel, they’d have spearheaded the dismantling of NATO upon the end of the Cold War. Instead, with America’s encouragement, NATO has nearly doubled its membership—from 16 countries when the Berlin Wall fell to 30 today.

With each new member, the U.S. government and American service members are tied to another far-off tripwire: Under Article 5 of the NATO treaty, an attack on any member country compels other treaty members to come to its aid. It’s the epitome of what Thomas Jefferson called an “entangling alliance.”

While the growth in the number of NATO countries and U.S. war commitments is unsettling, it’s the direction that’s been most troublesome: NATO expansion has marched the alliance relentlessly eastward, right up to Russia’s border.

To get a sense of how that’s perceived in Russia, imagine if, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia set out to reinvigorate the Warsaw Pact by inviting Mexico to join a military alliance created in 1955 to oppose NATO during the Cold War. Americans would find such a move equally perplexing and unsettling.

The way NATO expansion proceeded, however, was even worse than that.

An International Promise Broken, Over Emphatic Domestic Objections

During the diplomatic maneuvers leading up to the reunification of Germany and the withdrawal of Soviet forces, Western leaders gave repeated assurances to Moscow that NATO wouldn’t grow eastward.

The most prominent and emphatic assurance came from U.S. Secretary of State James Baker, in a 1990 meeting with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Baker said, “If the United States keeps its presence in Germany within the framework of NATO, not an inch of NATO’s present military jurisdiction will spread in an eastern direction.”

Several years later, however, NATO and President Clinton began considering just such an expansion—but not without controversy. American diplomat George Kennan, a towering figure in Cold War strategy who authored the policy of Soviet “containment,” was unequivocal in his opposition.

In a 1997 essay published by The New York Times, Kennan said, “Expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-cold-war era…Such a decision may be expected…to restore the atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations, and to impel Russian foreign policy in directions decidedly not to our liking.”

Kennan wasn’t alone. A bipartisan group of 50 foreign policy luminaries—including Cold War hawks like Paul Nitze and Robert McNamara—signed an open letter to President Clinton opposing NATO expansion.

“Russia does not now pose a threat to its western neighbors and the nations of Central and Eastern Europe are not in danger…we believe that NATO expansion is neither necessary nor desirable and that this ill-conceived policy can and should be put on hold,” the group declared.

In 1999, Clinton and NATO plunged forward anyway—reneging on the assurances given to Moscow by their predecessors—and the first round of NATO’s post-Cold War expansion brought Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic into the military treaty.

Subsequent expansion waves added another 11 countries, and the mutually beneficial buffer of states between NATO and Russia grew ever slimmer, vanishing in part with the addition of Estonia and Latvia.

Though Russia may have grudgingly accepted NATO’s membership nearly doubling since the end of the Cold War, it views the prospect of Ukraine membership far more gravely.

That central factor in today’s tensions first came to prominence in 2008, when, at a summit in Bucharest, NATO officials considered bringing Ukraine and Georgia into the pact.

“The George W. Bush administration supported doing so, but France and Germany opposed the move for fear that it would unduly antagonize Russia,” wrote University of Chicago professor and foreign policy expert John Mearsheimer.

No invitations were extended, but in a compromise that tilted toward America’s position, NATO issued a full-throated endorsement of Ukraine and Georgia membership as an eventuality: “NATO welcomes Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO. We agree today that these countries will become members of NATO.”

William Burns—who was then U.S. ambassador to Ukraine and is now Biden’s CIA director—warned Washington about Russia’s deep unease over the prospect of Ukraine joining NATO. In a 2008 cable titled “Nyet Means Nyet: Russia’s NATO Enlargement Redlines,” Burns wrote:

“Ukraine and Georgia’s NATO aspirations not only touch a raw nerve in Russia, they engender serious concerns about the consequences for stability in the region. Not only does Russia perceive encirclement, and efforts to undermine Russia’s influence in the region, but it also fears unpredictable and uncontrolled consequences which would seriously affect Russian security interests.

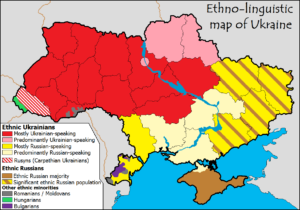

Experts tell us that Russia is particularly worried that the strong divisions in Ukraine over NATO membership, with much of the ethnic-Russian community against membership, could lead to a major split, involving violence or at worst, civil war. In that eventuality, Russia would have to decide whether to intervene; a decision Russia does not want to have to face.”

2014: A U.S.-Encouraged Coup in Ukraine

2014: A U.S.-Encouraged Coup in Ukraine

As NATO flirted with Ukraine as a military partner, the European Union courted the former Soviet country as an economic one. These are divisive ideas within Ukraine, with a majority of ethnic Ukrainians supporting EU and NATO memberships and most ethnic Russians opposing them.

In 2013 and 2014, the EU’s courtship would lead to bloodshed and the West-encouraged overthrow of democratically-elected, Russia-friendly Ukraine president Viktor Yanukovych.

Yanukovych had been negotiating an economic deal with the EU, but scrapped it in favor of a counteroffer from Russia that included Moscow buying $15 billion of Ukrainian government bonds and slashing the price of Russian natural gas.

Protests ensued and about a hundred protesters were killed. Western governments sensed an opportunity for a regime change that would install a government aligned with the West against Russia.

Senator John McCain flew to Kiev and joined protestors in the streets, as did Obama Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland and ambassador to Ukraine Geoffey Pyatt.

As Yanukovych’s hold on power neared its end, Nuland and Pyatt were heard on a leaked phone call working to maneuver their favored politician, Arseniy Yatsenyuk, into power.

“Yats is the guy,” said Nuland, who’d weeks earlier boasted that the United States had spent $5 billion after Ukraine’s 1991 independence to shape the country’s politics. When Yanukovych fled to Russia, Nuland’s goal was realized: Yatsenyuk became prime minister.

Just two days after the coup, Ukraine’s parliament alarmed the country’s ethnic Russians by pushing through a bill—without debate—withdrawing permission for the use of Russian as an additional official language in regions where Russian minorities comprise at least 10% of the population.

The anxiety of Russian and other ethnic minorities was compounded by the substantial presence of neo-Nazi elements in the Ukrainian nationalist movement. Given the devastating toll of Russia’s fight with Nazism in World War II, one can see how that’s a cause for unease in Moscow too.

Ukraine’s abrupt transfer of power gave Russia something else to worry about: the Crimea peninsula, which is not only home to a majority-Russian population, but also Russia’s strategically vital warm-water navy base at Sevastopol.

In 1954, Crimea was casually transferred from Russia to Ukraine by Soviet leader Nikita Kruschev, as a gift of sorts on the 300th anniversary of Ukraine’s unification with Russia. At the time, moving governance of Crimea from one part of the USSR to another seemed relatively inconsequential.

The transfer became extremely consequential in February 2014, with the prospect that the new, Ukrainian nationalist government might move to terminate Russia’s lease of the navy base.

Preempting that possibility, Putin ordered his forces to incorporate Crimea into Russia. With thousands of Russian troops already there on the navy base—and with the majority-Russian local population preferring Russian rule—the actual seizure was less dramatic than the media may have led you to believe.

Elsewhere in Ukraine, however, the post-coup experience has been marked by violence and thousands of deaths, as Russian separatists in the eastern Donetsk and Luhansk regions seek to establish independent republics.

The Russian concerns about the destabilizing effects of Western overtures to Ukraine, which were laid out by then-ambassador William Burns in his 2008 cable, have been substantiated. Meanwhile, though hapless U.S. interventionists may have hoped Ukrainian regime change would pry the Sevastopol navy base out of Russian hands, it’s only had the effect of giving Russia a firmer hold on it than before.

NATO expansion illustrates an intrinsic drive of any governmental body—to continuously enlarge its power and budget.

And in the Ukraine crisis, we vividly see what Richard Sakwa calls “a fateful geographical paradox: that NATO exists to manage the risks created by its existence.”

Make no mistake, NATO also exists to enrich the weapons industry, at the expense of citizens whose lives are put in greater jeopardy by NATO’s empire-building, which fosters antagonism with a country armed with 4,500 nuclear weapons.

To fully appreciate how intertwined NATO and weapons manufacturers are, consider this split-screen vignette from a 1997 New York Times story:

“At night, Bruce L. Jackson is president of the U.S. Committee to Expand NATO, giving intimate dinners for senators and foreign officials. By day, he is director of strategic planning for Lockheed Martin Corporation, the world’s biggest weapons maker.”

Poland joined NATO about two years after that story was published, and would go on to sign a deal to replace its Soviet-built fighter jets with 32 F-35A’s built by Lockheed Martin—at a price of $4.6 billion.

That’s just one representative example. As NATO’s expansion and needless antagonism toward Russia continues fostering tensions, the arms money keeps flowing.

Just last week, House Democrats—eager to demonstrate their firm resolve against an allegedly imminent Russian invasion that not even Ukraine anticipates—pushed for rapid passage of a military aid package, authorizing the spending of half a billion dollars the U.S. Treasury doesn’t have.

The counterproductive NATO-EU flirtation with Ukraine has been winding on for 14 years. With Ukraine ranking 122nd-worst in the world in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, NATO and the EU may wring their hands for years to come before ever tying the knot.

Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelensky seems exasperated with it all. Speaking on Friday about the lingering uncertainty of Ukraine membership in NATO, he said, “We want specifics, we need to have something that we can count on… Well, give us the reasons. Okay, we are not in NATO—okay, tell us that we are not in NATO. Tell it openly: we will never be there.”

Let’s tell Ukraine exactly that, and once again pursue Jefferson’s ideal of “peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none.”

This article was originally featured at Stark Realities and is republished with permission.

2014: A U.S.-Encouraged Coup in Ukraine

2014: A U.S.-Encouraged Coup in Ukraine