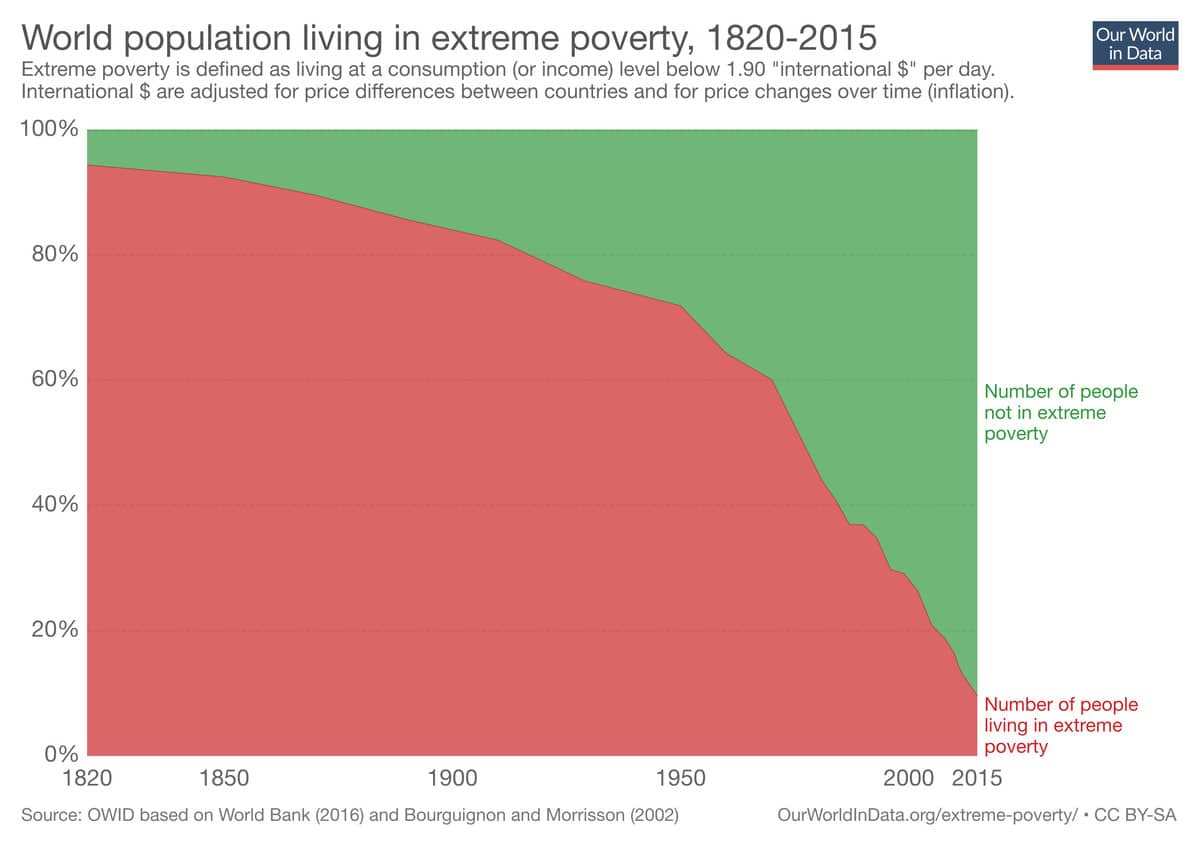

One of the best arguments in support of free market capitalism is how much capitalism has reduced extreme poverty. Between 1820 and 2015, extreme poverty plummeted from 90% to 10% globally in that span.

This statistic is one of the greatest accomplishments of mankind and should be celebrated as such. However, some argue that this statistic is not the achievement that capitalists say it is. In fact, they argue this graph is wrong and that capitalism has not been the motivator of cutting extreme poverty.

In a paper written by anti-capitalists Jason Hickel and Dylan Sullivan from 2022, they make the case that capitalism has not reduced extreme poverty like we think it has. The authors claim that 90% of the population did not live below extreme poverty line prior to 1820, that the rise of capitalism has deteriorated human welfare, and that socialist or social democratic movements after the rise of capitalism were the drivers behind the decline in extreme poverty.

Admittedly, the paper seems convincing at the surface. Unlike some other papers, the naked eye will not see the many faults. However, giving a second thought and analyzing their metrics will reveal the flaws.

From the abstract alone, the poor metrics can be seen. The authors define poverty in a relative context. They dismiss the fact that the resources at the time were significantly less than what we currently have thanks to capitalism and focus on the fact that it was possible to obtain the average standard of living without much effort.

This is like arguing it is better to be a farmer living in a mud hut and be happy because it is easy goal to hit than make fifty thousand dollars a year and barely afford rent.

The metric they use is price data to calculate a Basic Needs Poverty Line (BNPL). This consistently allows people to consume 2,100 calories, 50 grams of protein, 34 grams of fat, and various vitamins and minerals per day from the cheapest available foods in addition to other non-food items such as clothing, shelter, fuel, etc. The contents are not narrowly defined but can change as prices change.

The problem with this metric is that they ignore food quality and the quality of goods. For example, modern-day clothes are significantly better than the ones available in 1820 and more abundant. However, their metric does not care since they have clothing either way.

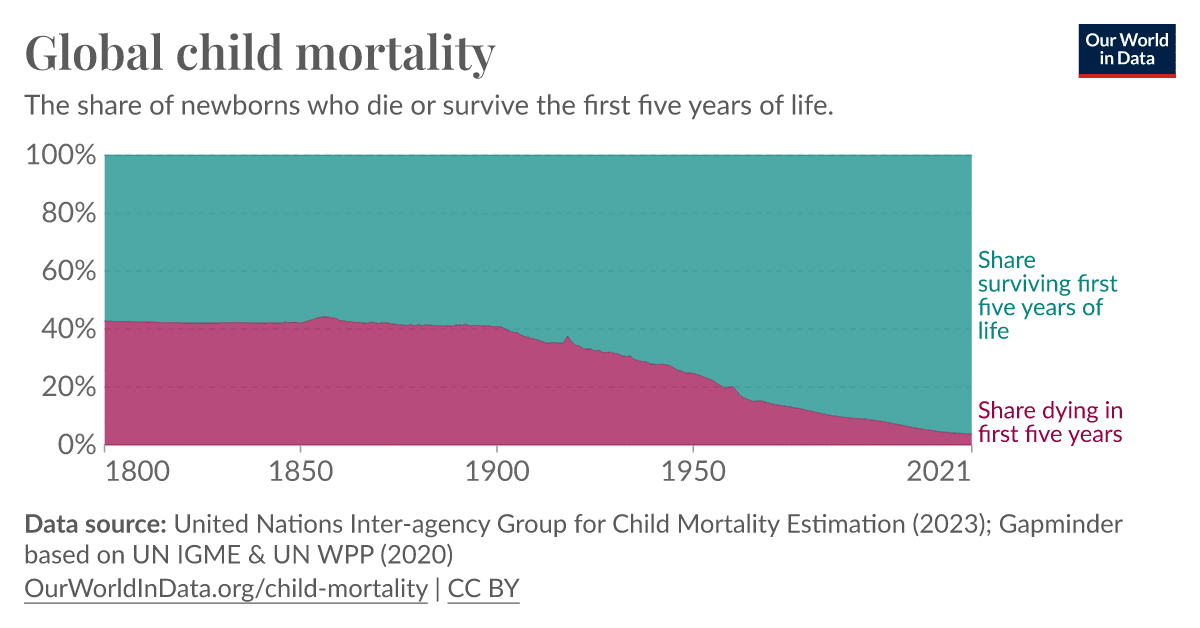

The authors also ignore the decline in child mortality between 1800 and 2021. In 1800, 40% of children died before the age of 5. In 2021, the number has fallen to 3.8 %, a remarkable achievement.

The last point of the paper argues that the major progress in living standards took off during the twentieth century with the rise of the socialist movement, which effectively removes any credibility.

This argument is a causation/correlation fallacy since the socialist states that did see economic progress was despite socialism, not because of it.

Take the Soviet Union. Communists love to point out that Russia went from a backward feudal country to an economic and political powerhouse that rivaled the United States.

However, what they do not realize is that 90% of Soviet technology had western origins, according to Philip Vander Elst. As even Soviet economists admitted, “Collective farms were so inefficient that even by the late 1930s the country fed itself mainly not from the collective farms, where capital investment were greater, but from individual farms and private garden plots lacking tractors and other mechanized equipment.”

In the book Back in the U.S.S.R, the authors look at whether Joseph Stalin’s leadership was necessary for the Soviet economy to achieve industrialization. The authors conclude that Stalin was not necessary for economic progress:

“Therefore, our answer to the ‘Was Stalin Necessary?’ question is a definite ‘no.’ Even though we do not consider the human tragedy of famine, repression and terror, and focus on economic outcomes alone, and even when we make assumptions that are biased in Stalin’s favour, his economic policies underperform the counterfactual. We believe Stalin’s industrialisation should not be used as a success story in development economics, and should instead be studied as an example where brutal reallocation resulted in lower productivity and lower social welfare.”

One example that skeptics of capitalism like economist Richard Wolff argue is that most of extreme poverty reduction came from socialist China. In a video posted on the Gravel Institute’s YouTube channel, he states, “almost of all that reduction in poverty has been in one country: China. Not where American-style capitalism was exported.”

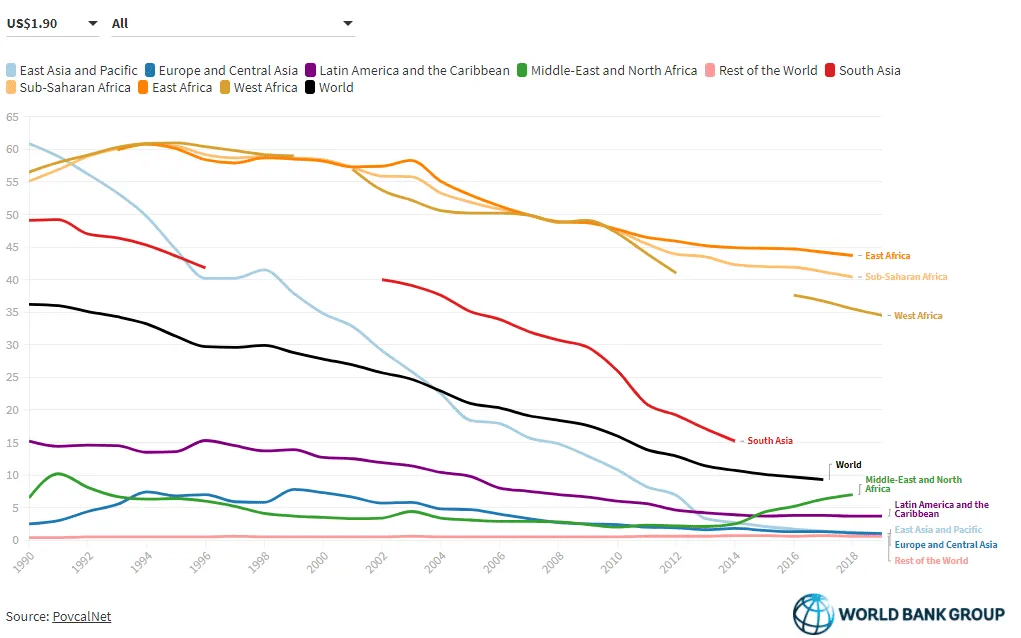

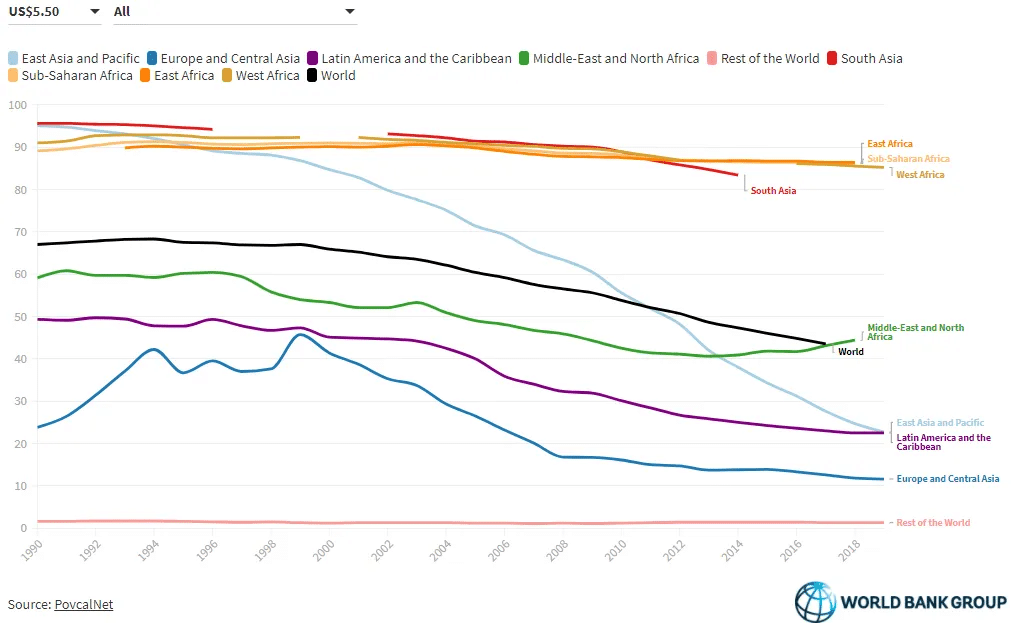

Wolff conveniently ignores that poverty has dramatically decreased even if we exclude China. Within the last few decades, the world has seen dramatic decreases in extreme poverty and people advancing to live at $5.50 a day.

Furthermore, the reduction in poverty in China has not come from the socialist policies that Wolff supports, but rather from introducing market reforms into their economy after Mao Zedong died.

When China began to introduce market reforms in 1978, their economy began to grow 7-12% every year. Under central planning, growth was at an abysmal 2% annually. As more urban laborers entered into the private sector instead of the public sector, the GDP grew exponentially (China’s GDP in 2017 was 24 times as high as it was in 1978). On top of that, China saw extreme poverty reduced from over 700 million to almost nothing thanks to economic liberalization.

The two most socialist countries the world has ever seen did not experience economic progress through socialist policies, but rather through market reforms that the authors of this paper despise.

Despite attempts by anti-capitalists, they cannot refute the fact that capitalism has indeed reduced extreme poverty by as much as 80%. Their poor metrics and causations/correlation fallacies fail at every attempt they make.