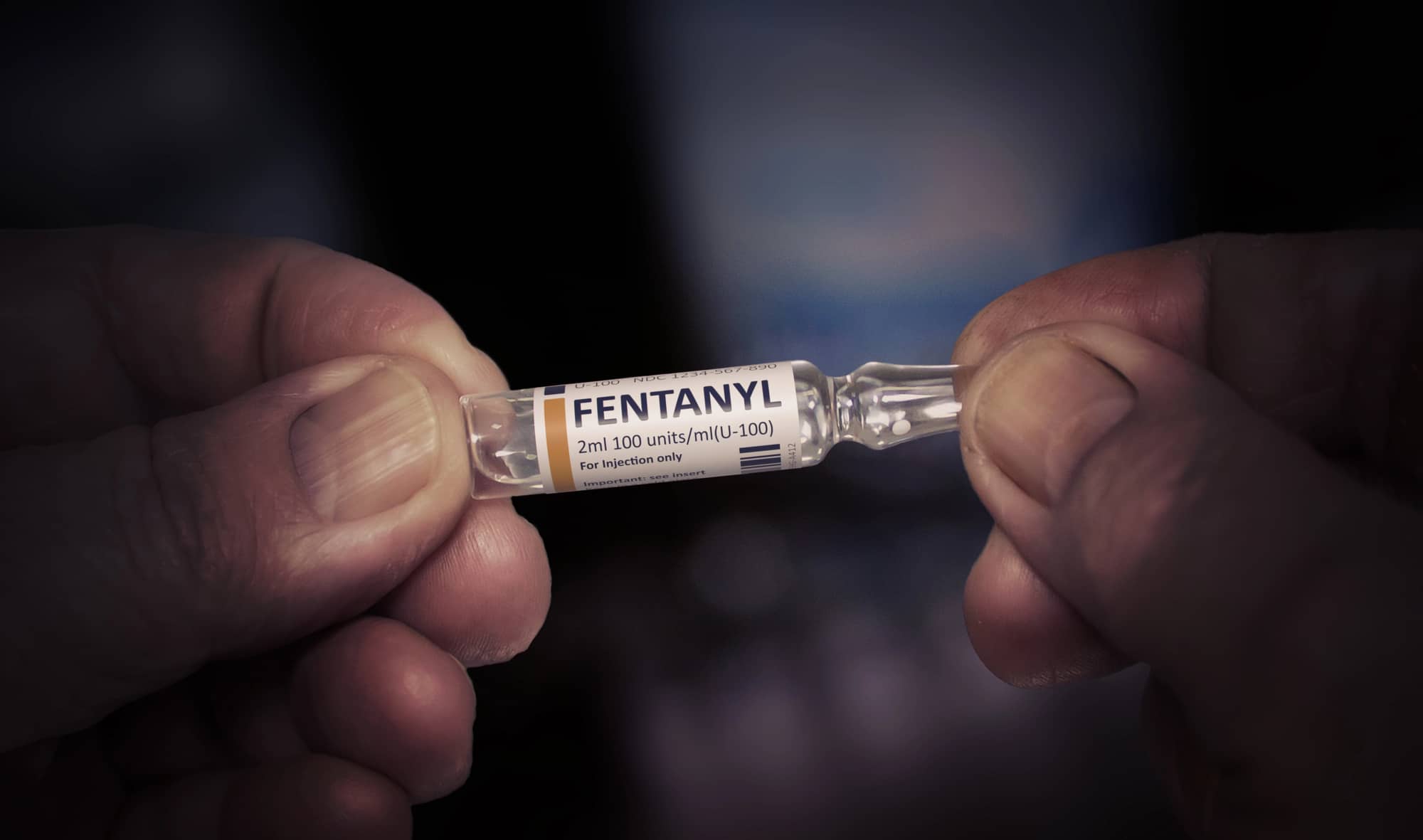

In the closing days of 2025, the White House turned an opioid crisis into a national security drama. Standing in the Oval Office during a Mexican Border Defense Medal ceremony on December 15, President Donald Trump declared that he would sign an executive order to classify fentanyl as a “weapon of mass destruction,” calling the announcement “historic.” Treating a synthetic painkiller like a nuclear bomb says more about Washington’s mindset than about the drug. Though drug overdose deaths declined in 2024, 80,391 people still died and 54,743 of those deaths were from opioids. Those numbers mark a public‑health emergency. Rather than tackle fentanyl abuse as a medical or social problem, the administration reframed it as an existential threat requiring military tools. Labeling a narcotic a WMD creates a pretext for war and sidesteps due process. This move grows out of a political culture that uses fear of invisible enemies—terrorists, microbes, drugs—to justify extraordinary power.

Past and present administrations have blurred the line between law enforcement and warfare. Since September 2025 the United States has launched more than twenty strikes on boats in the Caribbean and Pacific suspected of carrying narcotics, killing over eighty people. Experts note that little proof has been made public that the vessels contained drugs or that blowing them out of the water was necessary. Yet the assaults continued, and on December 10 the U.S. Navy seized a sanctioned Venezuelan oil tanker off Venezuela’s coast, sending oil prices higher. Trump boasted it was the largest tanker ever seized and said, when asked about the cargo, “We keep it, I guess.” Caracas denounced the action as “blatant theft.” The administration justified the operation as part of its anti‑drug campaign, but the target was not an unmarked speedboat; it was a carrier of crude oil, the sanctioned state’s main revenue source. Calling fentanyl a WMD makes such seizures look like acts of defense and blurs war and policing.

For students of recent history, this conflation of domestic threats with existential danger is hauntingly familiar. After September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush and his advisers claimed Iraq was developing anthrax, nerve gas and nuclear weapons. Vice President Dick Cheney insisted there was “no doubt” Saddam Hussein possessed WMD and was amassing them for use against America and its allies. Those arguments resonated with a populace still traumatized by the attacks. Fear allowed hawks to portray preemptive war as the only way to prevent a “mushroom cloud,” and in March 2003 the United States invaded Iraq. Investigations later found no factual basis for the claims that Iraq possessed WMD or collaborated with al‑Qaida. The smoking gun was a phantom, but by the time the truth emerged, Baghdad had been captured and the region destabilized for a generation.

One of the most tragic figures in that saga was Secretary of State Colin Powell. On February 5, 2003, he sat before the United Nations Security Council holding a glass vial he said could contain anthrax. He described Iraq’s alleged weapons labs and insisted the case was based on “solid intelligence.” The performance helped clinch support for war. Years later it became clear the intelligence was false and cherry‑picked, and no WMD were found. Powell later admitted the presentation was wrong and had blotted his record. Using a decorated officer’s credibility to sell a war built on falsehoods shows how propaganda can override reason.

The consequences of the Iraq War were catastrophic. The Defense Department records 4,418 U.S. service members dead in Operation Iraqi Freedom, including 3,481 killed in hostile action. Brown University’s Costs of War Project estimates that the post‑9/11 wars have cost the United States around $8 trillion and killed more than 900,000 people. About $2.1 trillion of that went to the Iraq/Syria theater. These figures exclude indirect deaths and future costs for veterans’ care. Millions of Iraqis were killed, injured or displaced, fueling sectarian violence and extremism. The war enriched defense contractors and expanded the military‑industrial complex while leaving ordinary people to pay the bill.

The Global War on Terror at home changed the nation in other ways. Within forty‑five days of 9/11, Congress passed the Patriot Act, which swept away restrictions on government monitoring. The law allowed roving wiretaps and permitted agencies to collect personal records without court approval. Secret programs like “Total Information Awareness” and the NSA’s “Stellar Wind” vacuumed up email, telephone and internet metadata from millions of Americans. By mid‑September 2001, the NSA had decided to surveil domestic communications without warrants. Officials claimed wartime authority for actions that would otherwise be criminal. The Global War on Terror also produced a prison outside the law: Guantánamo Bay. Since 2002, 779 Muslim men and boys have been detained there, most without charge, and as of 2022 thirty‑nine remain indefinitely detained, twenty‑seven without ever being charged. Three successive presidents have promised to close it and failed. Exceptional measures have become permanent as the security state has grown.

Even though the conventional Global War on Terror has wound down, the culture of endless war persists. The U.S. still maintains detachments of troops in Iraq and Syria and continues drone campaigns across Africa and Asia. These operations are rarely debated in Congress, and casualties are filed under “national defense.” In such an environment, designating a painkiller a weapon of mass destruction misdiagnoses overdose deaths as acts of war. Fentanyl kills through addiction, not deliberate mass casualties. Treating it like a chemical weapon invites a militarized response that has already begun with airstrikes on fishing boats and the seizure of oil tankers. The United States now claims the right to destroy any vessel it suspects of carrying drugs. Such strikes, carried out without public evidence or due process, amount to summary executions. The seizure of a Venezuelan oil tanker—and the president’s offhand comment about keeping the oil—suggests economic motives. For decades, anti-drug rhetoric has been used to justify U.S. interventions in Latin America while pursuing geopolitical and corporate objectives. The pattern is repeating.

The war on drugs has long served as a vehicle for state power. Agencies created to police narcotics have fueled mass incarceration and militarized policing at home, while abroad Washington has funded paramilitaries in Colombia, Peru, and Mexico. Violence intensified, corruption spread and drugs kept flowing. Fentanyl is the latest manifestation of that failure. Bombarding fishing boats or seizing oil tankers will not stem supply. Such actions provide contracts for defense manufacturers, justify bigger budgets and expand executive power while deepening resentment in the very countries whose cooperation is needed. If the United States wants to reduce overdose deaths, it must invest in treatment, regulate the pharmaceutical supply chain and address the despair that drives addiction. Declaring a drug a weapon will not heal a single addict but will feed a military‑industrial complex always in search of new missions.

America’s addiction to war has measurable costs. Each sortie, missile and deployment transfers wealth from taxpayers to contractors and normalizes the idea that national problems can be solved with violence. The Global War on Terror spawned extrajudicial killings, secret prisons and mass surveillance; it drained trillions that could have been spent on infrastructure, health care, or education. The war on drugs has filled prisons and militarized police departments. Now both have fused in the claim that fentanyl is a weapon of mass destruction. Endless conflict justifies endless power, secrecy and spending. A government big enough to police the world and its citizens is too big to respect their rights. When policymakers treat every crisis as a casus belli, citizens should ask who benefits. It is rarely the soldiers, patients or bereaved families. The beneficiaries are those who profit from war and fear.

History offers a clear lesson. When the government declares an emergency, citizens should demand evidence rather than succumb to panic. Americans once accepted, on the basis of false intelligence, that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction. The result was a war that claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and squandered trillions of dollars. Today the same government asks them to believe that an opioid is a weapon of mass destruction. Without skepticism, the public may again be led into unnecessary conflict. The proper response to a drug epidemic is medicine, education and community, not bombs and blockades. In a free republic, wars should be fought only when the nation is directly threatened. Fearmongering about WMDs—whether in Mesopotamia or medicine cabinets—serves the interests of a military‑industrial complex that never runs out of enemies. If Americans wish to protect their liberty and prosperity, they must refuse to let crises be used as pretexts for more war and remember that “War is the health of the State.”