One issue which motivates me substantially is war. War serves the powerful, and the powerful use ideas and norms to enlist the public in their preferred causes. I firmly believe that independent thought, and democratized moral reasoning, is completely essential in preventing war.

America used to be a place where free thought helped suppress possible wars, but the powerful have changed how we think. To suppress what’s good about American morality, the powerful have exploited the parts which are bad. America is the best, and the worst the world has. If we could only free the good parts from the bad ones. I feel personally responsible in finding the fix.

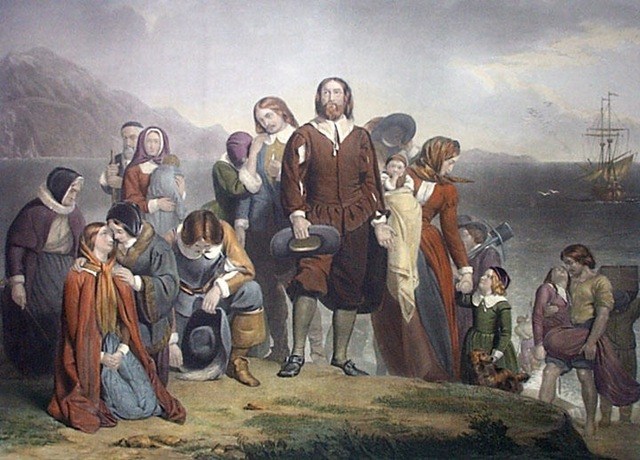

One of my ancestors rode on the Mayflower. He was on the first voyage of that ship. William Brewster was his name, the most senior religious leader of the community to travel to the New World. That’s my father’s side. On my mother’s side, we descend from some Scottish Highland prince who emigrated to the colonies well before the whole Culloden mess. The “prince”, a chief’s brother, was a staunch Presbyterian, and something of a religious philosopher. My great-great grandfather from that side was a preacher who took to the prairies of Wisconsin to make sure the pioneers had some religion to take along with them West.

My father’s mother was born in Berlin in the 1930’s. Her father was a state-funded preacher who inevitably took the side of the National Socialist Party when the time came. He had divorced her mother due to an affair with the church secretary. The last time my grandmother tried to visit him as a child, he harshly criticized her insolence.

“Don’t you know know that it says in the 10 commandments, honor thy father?” he chided.

My grandmother replied, “Doesn’t it also say, thou shalt not commit adultery?”

My grandmother was good at math, so the Nazis sent her on a train to the mountains to “preserve German youth”. She ran off from her assigned, resentful, country foster family. She snuck back into Berlin. She wasn’t supposed to be there, and my great-grandmother wouldn’t have had enough food (she was deemed unsuitable because she took the blame for her husbands’ affair, since his punishment would have put him permanently out of work). This was solved by my great-grandmother taking up with a military officer to get food for her kids. As for the officer, he died in the famous flooding of one of Berlin’s train stations, when it was bombed by the Allies. The adulterous preacher died of exposure in the dark belly of a bomb shelter, having untreated conditions related to childhood polio, which immobilized him. The only thing he left to my grandmother was the family grand piano. It was smashed by an American bomb, along with the rest of the apartment, and entire building.

Following the German defeat, my grandmother fled East to family. Climbing out train windows and walking home through the woods, my grandmother endured Soviet checkpoints, the occupation, and somehow finagled a student visa to Illinois (before the Cold War turned too hot). She still lives in there.

I had a conversation with her once about religion, relationships, and so forth. She quipped, “It all comes out in the wash.”

My mother’s father was a sort of orphan raised in Milwaukee by his German immigrant grandparents, who didn’t speak English. His grandfather’s rule: nightly readings from his German Lutheran bible. This child, my grandfather, grew up to mostly shrug at religion. He was a nuclear physicist and rocket scientist. He was present at the first test of a radar system by the US at Aberdeen proving grounds. He was sent to Germany in Operation Paperclip to bring back some rocket parts (I don’t think he would have crossed paths with my paternal grandmother). As the military developed its rocket program, he – a civilian employee of the Navy – recommended that these weapons could be used for scientific purposes. They accepted his proposal, but shortly afterward, he moved on. In his place, a man named Van Allen was appointed to lead the project which first discovered the magnetic bands circling the Earth.

This same grandfather was involved with various aspects of the rocket program. My mother recalls an evening at home in which one Werhner Von Braun presented her family with a slideshow about Mars. My strict, German immigrant, government scientist man, grandfather had four girls, and no boys. He wanted them all to get PhDs. His wife was a strong supporter of FDR and civil rights. Not at all German, she was a vaguely socialistic, moralistic Unitarian Universalist (and possibly agnostic) Scots-WASP. Before he died, in the 1980s, my (probably agnostic) maternal grandfather commented that he was quite impressed with one up and coming politician from Tennessee named Al Gore.

Neither of my parents cared much for strong religious sentiment. My father vaguely encourages the idea of a Christian faith, but it’s non-committal. He’s pretty Gen X, for a baby boomer. My mother is terrified of the very idea of faith in a God, but her life is governed by a notion of “morality” which her strict and moralistic, but probably agnostic, parents imbued in her.

My parents divorced when I was young, so I couldn’t really tell you what sort of paradigm they might have hoped to raise me with. That said, my family’s legacy has left me with certain notions. In particular, I have a notion of America’s legacy which transcends the standard conventions of American nationalism.

1776 was probably a good idea. My Scottish ancestor believed in it enough to enlist at 16 (he was tall, and lied about his age). Ambushed by Indians during a rest stop, his company never made it to battle. This ancestor did, however, make it to Canada. That’s the story he told, at least, to the pension office about why he was drawing a military pension from the United States federal government and the King of England (he had also enlisted in the war of 1812, on the other side).

Abraham Lincoln is an idol of American nationalism, a saint who defines the country’s identity. Sure, my Ohio Yankee ancestors were proud, staunch, committed Republicans. However, one of them was there in Sherman’s Georgia march. Lincoln’s legacy is as much his, in a certain sense.

America became an international power player in WWI. I wonder if my other ancestor considered what that would mean, while he was busy in the Army scribe division helping copy back drafts of the Treaty of Versailles, in France.

Joseph McCarthy is a scoundrel in American political history. To my Wisconsin bred grandmother, he was a lousy date whom she declined when he came to ask for a second – that is, long before he was a U.S. Senator. I suppose McCarthy lucked out, because my grandmother’s second cousin or something was Aldrich Ames.

Despite all this family history, I was always more interested in it than any of my family members. Maybe it’s because of my parents’ divorce. Maybe I wanted to feel like I belonged to something. My family’s varied American legacy was just life, and barely worthy of mention. I’ve had to patch a lot of it together.

In high school, many of my classmates were immigrants. Usually from Asian countries. I was a happy little, loyal Boy Scout. I liked saying the Pledge of Allegiance before class. Some of my classmates were into the America thing, but most weren’t. It made me think about how I might care more about American traditions and legacy than they did, even though there were American citizens too. Only later did I realize that my family’s American legacy is older and deeper than many rather contemporary trappings of American nationalism like the Pledge.

My immigrant friends had heritage, and family, in other cultures and countries. They would visit China over the summer, bring Chinese food to lunch, ironically wear Mao pins they received from uncles overseas. I had Jewish friends who celebrated Rosh Hashana, and had bar mitzvahs, and who would visit Israel.

What I had – well it wasn’t a stable nuclear family at home – was the same sterile trappings of nationalism as everyone else. My Chinese, Jewish, Polish-American, Peruvian, and Korean high school friends all said the same Pledge as me. If I was into Boy Scouts, it was because I was a nerd, not because I was somehow more American.

It didn’t bother me that I didn’t have a heritage. I sort of had a German thing, but then there were too many Nazis involved for it to be an area of focus. Besides, Germans were among the first and oldest European immigrants to the United States. They were practically fully American before any of the other Euros showed up, right? At least they were white enough to be part of that “white American male” category that no one is allowed to be proud of at all. It’s an identity you’re not allowed to have. I guess I have enough privilege not to need one.

As I learned more about the world, as I grew older, I started to connect with America’s legacy more deeply.

People always talk about white Europeans stealing land from Native Americans. You know the famous Comanche horse tribe? They obtained their horses in 1680, and became a distinct group in 1700. The first Mayflower passage was in 1620.

Of course, many American Indian tribes were unfairly and cruelly treated by European American colonizers. However, weren’t the Pilgrims themselves fleeing persecution, and seeking a better situation. In what sense then was this one specific group of initial Plymouth Rock settlers all too different from the Comanches, in terms of origin stories? I would never try to justify what was done to most of the American Indian peoples, but my family history has a relatively strong legacy in North America.

From 1620 to 1791 (US Constitution) is 171 years. 1791 to 2018 is 227 years, a single generation’s worth of time longer (171 after 1791 would be 1962, around when my mother was learning how to type in Jr. High School).

For a time, I became Mormon. The Mormons were a religious cult which formed out of the Yankee mix of liberal, evangelical, ecstatic, superstitious and milleniarian religious belief. The two “Great Awakenings” which created the religious conditions which led to Mormonism included social changes which predated the Revolutionary War. Mormonism is loosely connected to English folk superstitions about angels and magic which were wiped out by 19th century pragmatism, and later 20th century modernism. The Mormons believed that North America was a special land in the eyes of God, that this same God caused the United States to come into being through His specific intent, and also dabbled in its own notions of theocracy. The United States, at various times, had minor wars with the Mormon nation in the West.

American history likes to create an image of a single course of history for the nation. Lawyers, especially, like to imagine that the unitary law of the land sprung up from the soil in a single thrust, a simultaneous, spontaneous singularity which created all the American nation from dust.

The truth is, there have been numerous “American” nation-states. The Independent Commonwealth of Virginia. Massachusettes. The Republic of Texas. The Confederate States of America. Deseret (Mormons). Hawai’i. Not to mention the Indian nations (as they existes post-Columbus, in commerce and communication with European civilization). Lincoln’s “United States” is not the only socio-political story in the broad historical category called “America”. New England, until Lincoln, had its own self-conceived identity, one which warmed to its mother nation much more than its Southern allies during the early 19th century. Before and after 1776, New England might have been its own nation-state.

My personal desire for identity led me to join the military, and then later to leave it. As a white American with no Nona to make pizza, what’s my version of some uncle’s Mao pin to wear? I wonder if apple pie will be taboo some day? Turkey? Nah, it’s too delicious right?

Speaking of Turkey, I like Thanksgiving. My ancestors have been celebrating it since, um, well I suppose since my ancestor said grace at the first one. That was a long time before July 4, 1776.

All in all, I mean to say that I have a developed strong sense of what America means. It’s not about aircraft carriers and F-22 fighters. It’s not about security operations in support of some international legal order. It’s not about Hollywood and hip hop (although the latter is much closer to the mark than the former categories).

I believe that America has an essential identity. That is, America is best defined, in my opinion, in a certain way. America is a word that, as an idea and identity, means something. It doesn’t apply to all things for all time, that occur in the middle part of North America. However, it’s a real social and cultural force here. For better or worse.

How do you define a country? France, for example, could be defined by cheese, wine, and lunatics.

America is defined by evangelical millenarianism.

America is a project. It is the legacy that people like the pilgrims deliberately sought. When my Aunt bused down to Southern sit-ins, she understood that this is what people like her did. It wasn’t the fulfillment of a social fad, for her. She wasn’t trying to earn her recognition in the polity. This was just being American.

America. Its existence is purposeful. Its aims are utopian. But what are its ends?

It’s easy to think of America as the United States, and its agency exercised through what is called the American Empire – that collection of military, economic, and covert powers. This isn’t an accurate appraisal of what America is, or was. America’s essence was always something more abstract. America is also a tragedy.

I’m proud, in many ways, of America and being American. Our moral idealism has sustained a highly economically productive society which exists without many of the more obvious class boundaries that plague other nations. One could talk about the Puritan work ethic, but one could also talk about notions of individual responsibility and free thinking pragmatism. America has big race problems, but then again, given the diversity in America, in proportion, there’s a remarkable amount of social harmony.

My mother’s generation is extremely proud of the civil rights movement. It takes the form of some crossbreed of a fetish and catechism for them, but still, it is something to be proud of. Given historical racial attitudes in America, the ability of American culture to rally behind a radical revision of those attitudes in a single generation – it’s pretty remarkable.

One of America’s less popularly discussed strengths is our scientific prowess. Sometimes other countries chastize America for claiming innovations which they insist were developed first, outside of America. Fine. A casual review of all innovation proves that America is the world’s innovation powerhouse.

Within American culture, I believe, is the formula for human flourishing. It’s a philosophical thing. It’s a moral paradigm. In America’s traditional culture, we possess clear notions of the existence of abstract right and abstract wrong. Consequently, we believe in abstract truth. This empowers individuals, over authority, over community, to insist upon and push for principles. Principles, while not value-less, are easier to reproduce with less social context. Ideas can spread in a way that is orthogonal to power control structures. Relative to social authority, independent moral ideas are renegade.

The American revolution was a product of independent moral thinking in the churches leading to a rejection of the idea of the King’s authority.

I’ve lived for many years in multiple countries. American thinking is pretty unique. Most cultures seem to rely pretty heavily on accession to group consensus, or authority, or the opinions of superiors. The idea that morality is democratic, that even the low can morally reason, and that moral ideas can trump custom and authority – this is as American as you get.

A 19th century Unitarian preacher named William Ellery Channing expressed the apotheosis of the idea in proclaiming his faith community’s remarkable position on God and His moral authority:

“We conceive that Christians have generally leaned towards a very injurious view of the Supreme Being. They have too often felt, as if he were raised, by his greatness and sovereignty, above the principles of morality, above those eternal laws of equity and rectitude, to which all other beings are subjected. We believe, that in no being is the sense of right so strong, so omnipotent, as in God. We believe that his almighty power is entirely submitted to his perceptions of rectitude; and this is the ground of our piety. It is not because he is our Creator merely, but because he created us for good and holy purposes; it is not because his will is irresistible, but because his will is the perfection of virtue, that we pay him allegiance. We cannot bow before a being, however great and powerful, who governs tyrannically. We respect nothing but excellence, whether on earth or in heaven. We venerate not the loftiness of God’s throne, but the equity and goodness in which it is established.” (Unitarian Christianity, 1819)

This sentiment concerning God’s subjugation to moral rectitude filtered also into Mormon teachings:

“Now the work of justice could not be destroyed; if so, God would cease to be God.” (Book of Mormon, Alma 42)

All this goes to show how deeply the notions of democratic morality had seeped into American culture. Of course, I attribute America’s success – beyond its luck – to this feature.

In spite of its successes, however, America has deep flaws. Our moral paradigm comes soured, poisoned even. Protestantism, the renegade movement of the Middle Ages, faced its own renegades the second it overthrew extant Catholic power structures. In my opinion, using a secular interpretation of its doctrine, Calvinism in particular developed into a toxic political and social ideology in order to suppress its own renegades.

Calvinism is the spiritual expression of the idea, “rule of law”. While this doctrine replaced the also loathsome, “rule of kings”, it comes with its own bag of troubles. It should instead be called, “absolute rule of absolute law”. Understanding that America’s miraculous culture of morally empowered individualism is and has always been poisoned by a strain of Calvinistic absolutism is key to understanding American social and political history.

The modern world, in my opinion, is built on America’s moral, cultural, and economic strength. America now, in the post-modern era, is trying to shed itself of its remnant Calvinism. Unfortunately, Calvinism’s descendants are shedding American of its morality, but holding onto its absolutism. This must be corrected, for the sake of America, but also for the sake of the world.

I won’t reject America’s evangelistic spirit. I truly believe the modern world is built upon fundamentally American notions. If we lose these, the world will revert back to what it was, or to something worse. Something has to replace that which is being torn down.

Many wax on about “Western civilization”. I’m not satisfied with those people and their agenda. They want it to be about St. George and his dragon, or something. It’s not about “enlightenment” either. In my opinion, the foundation of world prosperity and order, modern liberty, and economic productivity, is the democratization of morality through the freedom of thought. Yes, illiberal places can reap the benefits of what is done in liberal places. That’s just what’s going on, I think. Consumers can eat up a surplus without producing its replacement, for a time.

Some aren’t entirely happy about America’s moral and idealistic legacy. One example whom I often cite is Thaddeus Russell, author of Renegade History of the United States. I disagree with Russell philosophically. However, I agree fundamentally with the spirit of Russell’s argument that renegades have made America into the pleasant, enjoyable place it is today. I argue that these renegades – prostitutes, drunks, dancers, immigrants – achieved what they did not by fighting against morality, but rather by fighting for different moral conclusions. They exemplified, not a post-modern rejection of morality, but the American ideal of democratic morality. Their enemies were always the most Calvinist of American moralists, and in many cases it was America’s non-Calvinistic moral tradition which paved the way for the public to accept differences. “Send us your poor…”

I believe that renegades are a necessary antidote to America’s Calvinism, and also to anything like it. America’s miraculous moral idealism only works when it is freed from absolutism. We need renegades, and we also need moral reasoning. Ideological post-modernism, in my opinion, is just a new road to ultimately strengthen the Calvinist social paradigm.

Liberty itself depends on morality, and also the championing of moral renegades. The renegades unbind morality, they set it free to evolve and develop without having to lose it altogether.

It’s critical that America return to its culture of prioritizing moral reasoning, but that it do so while also sticking up for moral renegades.

What is liberty, really?

How do you define liberty? I think many “libertarians” would refer to the non-aggression principle, the politics of live-and-let-live. Still others would vaguely point to “freedom”, despite the stark opponents of liberty invoking superficial freedom to justify their statist designs. Libertarianism is pro-property, but then again, maybe it’s anti-rulers. I think the touchstone for liberty is pretty simple.

Liberty means the freedom to decide for yourself what your life’s purpose is, and where its meaning comes from. Liberty says that the truth is out there, but you get to figure out what you think it is yourself.

Nobody knows, really, what the purpose of life is. Life is almost nothing but a self-referential search for its own meaning. It’s completely inappropriate to judge what life’s purpose is, for other people. In a certain sense, it becomes clear that the search for meaning is life’s purpose, and it includes the whole spectrum of answers to that question.

Liberty, then, is the principle which leaves to the individual person the right to find their own answer to this question – the entity which, through consciousness, perceives meaning, and through physical agency, pursues purpose. The details of how or what property is, or which ethics are preferred, all fall under this umbrella principle.

One thing I hate about Progressivism is that its first principle is to rob individuals of the right to find meaning. Progressivism boldy observes the absence of supernatural meaning, and decisively settles on a purpose for life. Progressivism perceives comfort and survival, the continuation of life into pleasant leisure, as a universal good. Perhaps these things are universally good, but there are wrinkles aren’t there? Neither is progressive politics shy about ruffling feathers to reach their desired ends. Progressivism declares that government’s role is to shape society, to contain society’s natural impulses, and redefine for it what its values ought to be. The intellectual, academic, and expert join together to correct society’s natural errors. This is progress. Progressivism is the “elimination of bad outcomes”, indifferent to cause and consequence. One cannot maintain a conception of progressive politics without firmly rejecting the idea that individuals perceive meaning in life, and pursue their own purposes accordingly. Post-modern Progressivism doesn’t even countenance the existence of meaning, reducing individuals to infant meat-sacks who feel pain and pleasure, but whose thoughts are arbitrary and probably harmful if unmanaged.

What’s interesting about Progressivism is that it descends from an ideological phenomenon which has radically different surface features: Calvinism. In a certain sense, there is a genealogical relationship between the two, as New England Puritans created and stewarded the institutions of academia in America which later innovated many feature of progressive politics. Calvinistic features have crept into post-modern “cultural Marxism” as well.

Calvinism is a theological position within Protestant Christianity, but it is also a moral-social-political paradigm. Despite the direct connection between the sons of the Puritans, and contemporary progressive academics, I believe that the overall moral-social-political phenomenon which created Calvinist doctrine could manifest independently at any time. Radical statist politics in America didn’t need a genealogical relationship to New England Calvinism in order to emerge. The historical relationship, though, must have contribute to the result.

The link between Calvinism and Progressivism has been pointed out in libertarian circles, however, I credit Thaddeus Russell as the greatest contemporary herald of this connection. Thaddeus Russell is not a libertarian. What he, a historian, has done is demonstrate that moral norms have oppressed people, and how those who resisted moral norms have shaped society and liberated it. Liberty – finding and pursuing your own meaning in life – has been helped by history’s “renegades”. These are people who do what they aren’t “suppose to”, according to society’s rules. Russell’s notions are borrowed heavily from Michel Foucault, but I believe he takes them farther than Foucault into a new territory where true liberty lies. It seems that Russell understands that Progressive intellectuals often invalidate the moral conclusions of individuals, which he considers to be inappropriate. Since both Russell and many Progressive intellectuals borrow post-modern ideas, I couldn’t really say who is the better or worse post-modernist. Although, I hear that Foucault is difficult to grasp, and so people use him in all kinds of contradictory ways.

In my own philosophy, the active principle of liberty is something I call free moral reasoning, and also free moral agency. This is right to have one’s own moral reasoning validated by society, to be given permission to freely come to moral conclusions by oneself – presuming one has engaged in a process of reasoning to arrive at these conclusions, and can represent that process to others. Free moral agency is the right to act in accordance with one’s own moral reasoning, provided this action doesn’t interfere with the free action of others.

The idea that one’s own thoughts would not be validated by society is an idea which must be attributed to Foucault. I disagree with Foucault immensely, but he deserves credit for this observation. Those with power have controlled what people are allowed to say, think, and believe in order to control those people. This is more than a matter of rules, laws, and punishment. The powerful have always employed ideas, and enforced ideas, to enforce their rule. A society in which people are allowed to think differently from one another is a radical one, even in today’s world, and a unaccommodating world for the power hungry.

My disagreement with Foucault centers around the fact that I believe that his and especially his compatriots’ politics is infested with a dangerous need to reject free moral reasoning. Foucault seems to equate the constraints which prevent free moral reasoning with moral reasoning itself. Foucault seeks to reject ideas themselves, as social constructs, and rely on non-rational guides to human existence. Sexual passion is an example of an unbiased expression of consciousness, in Foucault’s mind.

I find this idea to be very dangerous. Denying moral reasoning is as bad as constraining it. Human society will find a way to coordinate itself, and power players and ideas always emerge to fulfill this purpose. Our goal should be to encourage the ideas which promote free moral reasoning, and non-aggression. To reject ideas leaves the door open to brand new impositions, leaving people impotent to resist them. As I’ve argued before, nature itself seems to provide a few social instincts. These instincts, unchecked by rationality, lead to oppression and unneeded suffering. Power prestige competition, adultery, abandoned children of undesired mates, a paradigm meant for resource scarcity and primitive technology incompatible with the higher order reasoning and more complex, nuanced social organization necessary in a technological society.

Progressives seem to use post-modernism extensively. Again, I don’t know if they are using it accurately, or merely exploiting some of its language to support their ends. Still, as I said, Progressives invalidate moral reasoning itself using post-modernism, reducing individuals to passionate meat-sacks. Both systems end up invalidating the personal moral conclusions of individuals.

Foucault it seems, and what I call the left, generally, are plagued by the legacy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau conceived of a primordial world before society, which he idealized as paradisaical. Original sin drove man from this paradise, that sin being civilization, that is, rules and norms, rulers and law.

From what I understand, Rousseau knew that his primitive world was full of starvation and violence. It wasn’t so match a matter of idealizing it, but rather using it to critique rules. It was meant to be used as a rationalization for the creation of a state which somehow abolishes the rules and standards of society, using force instead of shame to promote order and abundance. That’s how I interpret the idea.

Rousseau’s social theory is clearly connected to both Marxism and Post-modernism. Both treat ideas as synthetic things from which we must be liberated in order to return to paradise. I think this kind of thinking can be categorized very neatly in psychological terms.

In my opinion, leftism, and Rousseau’s social theory, are products of a solipsistic world view.

Solipsism

1. Philosophy. the theory that only the self exists, or can be proved to exist.

2. extreme preoccupation with and indulgence of one’s feelings, desires, etc.; egoistic self-absorption.

I define the difference between children and adults in the following way: children have trouble understanding that their emotions aren’t existential primaries, and adults are better able to perceive cause and effect, as well as the emotions of other people. I don’t know why leftists are solipsistic. Indeed, it could be the very social and moral constraints under discussion which create leftist psychology. Being denied the ability to pursue what one desires, the invalidation of one’s own emotional state, leads to an emotional complex that fetishizes the gratification of these desires. A perpetual quest for the emotional validation which never came. I think the children of Puritans, rabbis, and priests would likely be strong candidates for leftist intellectuals.

A solipsistic world view concludes that other people, not reality itself, is the source of constraints. The idea that resources are limited doesn’t apply. Other people – oppressors – create constraints, and so paradise comes from opposing the constraints and the people who impose them. It’s no wonder leftist revolutions often collapse, when the resource reality hits the fan.

Post-modernism, that of Foucault and Derrida, falls into the solipsistic trap. They hold that ideas aren’t valid, but perhaps the experiences of the consciousness are. This is solipsism, a quest to validate the consciousness and its passionate experiences, and a desire to disregard logical evidence by rejecting any idea of natural constraints, blaming them entirely on human repressors.

In my view, there is reality. There is truth. We might not be able to completely know it, but there is natural evidence which is as consistent as our own conscious experience. If we account reason as an experience, then we can conclude that there are many natural “truths” which are more consistent than the places to which our mere passions lead us.

When social norms are abolished, it doesn’t always liberate people.

As I mentioned elsewhere in an example of this, Thaddeus Russell sometimes praises black American culture for being more liberated that white American culture. I agree with his analysis, in that black culture is more physically and sexually liberal, traditionally, than white culture. However, my opinion of black culture is that in some ways it is can be more repressive of the individual than white culture. In many cases, strong group solidarity in black culture prevents people from escaping the constraints and expectations of their community. The difference between sexual mores and social mores here is that the former are imposed ideologically (religion = don’t sin = don’t have sex) whereas the latter are imposed naturally. No philosopher indoctrinated any black Americans to have a culture of group solidarity, it happened anyway. Thus, I don’t agree that ideas and social norms are the unique source of individual repression.

All norms, ideological or natural, repress. All norms also serve some purpose, organizational, or moral. Some ideological norms are used to control and exploit. Other norms arose to liberate people from natural constraints (don’t steal, don’t rape). Sometimes norms liberate on the whole more than they repress. There is no single stance one can take on norms. Frankly, I don’t think we can ever escape norms. Thus, we are better off consciously discussing and evolving our norms towards our preferences. We ought to have moral stances, but we should expect and welcome competitive points of view about what’s moral.

Foucault’s rejection of norms and ideas is something I consider to be childishly solipsistic. It’s a dodge of discussing possible benefits of moral norms, I think because Foucault had a set of contemporary norms that he greatly disliked.

Despite it all, we owe Foucault, and also Thaddeus Russell, a debt of gratitude

Although I disagree with the post-modern rejection of moral judgment, I agree with its conclusions about one crucial thing.

In my own philosophy, I believe that we can say, “this is a sound judgment.” Here, “sound” implies appropriateness, pragmatic usefulness, contextual consistency.

I agree with post-modernism that the following language is inappropriate: “that is an invalid belief.”

I don’t think the concept of validity exists. Rather, validity in this case implies a validating authority.

Valid

adj

1. sound; just; well-founded:

2. producing the desired result; effective:

3. having force, weight, or cogency; authoritative.

It may seem that the first two definitions meet my approval. They do. However, the last definition invalidates this concept for me.

What matters to me, in terms of truth, is contextual consistency. I do believe that an idea can be consistent or inconsistent with natural evidence. I do believe that we can make sound judgments about circumstances related to objective reality, or rather, consistent natural circumstances which are external to human consciousness or human agency.

When an argument is declared unsound, it begs the question: why? Why do you call that argument unsound? Soundness, harmony = consistency. Your argument, to be sound, must be constructed. If unsound, where is there inconsistency in your construction? If my preferences differ from yours, then your construction could be inconsistent with my beliefs, and your argument unsound.

Let’s imagine someone who believes in supernatural truths. They might argue that your scientific theory is inconsistent with their beliefs (for example, the theory of evolution). To them, it is unsound. Then again, you could in turn argue to them that their actions and other beliefs implicitly accede to the consistency of scientific reasoning. You could call their supernatural beliefs unsound. Context defines soundness. Clear moral reasoning discovers context. Open moral discourse discovers boundaries of belief. Boundaries of belief define realms of social interaction. A concept of moral territory, or moral proprietorship, is essential in imagining a truly morally diverse, free society. Respecting boundaries is a two-sided proposition.

In contrast to the notion of soundness, is the notion of validity. To call an argument invalid is to suggest that the argument is not allowed. It begs the question: not allowed by whom?

From Foucault, we understand that social norms are used to control people. Authority creates ideological structures in order to create lists of valid and invalid ideas. Using ideas to control people is a much more potent, and common, form of rule than the use of political violence. Most power is exercised socially, not politically, in my opinion.

Thaddeus Russell’s great gift to Libertarianism is the understanding that liberty must be found by looking at social structures, as well as political structures. Libertarianism has the non-aggression principle, which says that political authority cannot initiate violence, only use force in reaction to force. I believe Libertarianism also needs a social non-aggression principle.

Do not invalidate the moral reasoning of others, unless their ideas and actions represent an attack on the validity of yours.

Calvinism’s stain on the American dream, and its daughter Progressivism

“Real power is, I don’t even want to use the word, fear,” – Donald Trump, to Bob Woodward

The sense of self-preservation is one of the most consistent feelings in the human experience. It’s what causes us to remain alive. Fear, the emotion which connects to the sense of self preservation, thus, ties in to almost all decision making. No wonder that powerful ideas invoke fear. Fear appears very consistently in our processing of risk and reward, the fundament of our decision making process.

19th century Christian American critics of Calvinist doctrine proposed that Calvinism rules the human heart through fear. Fear of burning hell. In contrast, they thought that true God rules the human heart through love. This, metaphorically, is the basis for an understanding of morality which converts it from America’s Calvinistic negative morality (what you should not do) to a positive morality (what you should do). The shift from moral negativism to moral positivism is the paradigm which, I believe, will rescue morality for the future.

To save American morality, we have to reject Calvinism. We have to understand Calvinism. I believe that history reveals exactly what Calvinism is.

During the early Protestant reformation, many European municipalities were rejecting the Catholic Church. In some cases, such as in Lutheran Germany, the local Catholic leadership would convert over to Protestant beliefs. In other cases, the clergy was driven out of town.

One such case was in Geneva, Switzerland.

One can observe a connection between the departure of Geneva’s ruling bishopric, and the ascendancy of a wealthy class who took the reins of power for their own benefit. One can also observe, with the departure of religious authority, a liberated morality on the part of the town’s citizens. With the rise of Protestantism in Geneva, was also the rise of libertine behaviors.

In a weird way, Geneva here reminds me of America’s revolutionary Philadelphia. With the departure of the King’s authority, the colonies began a wide scale rejection of authority and norms. Liberty and libertinism rose together, initially. In Philadelphia, a power hungry and conspiratorial town council began to rule with an iron fist. They famously clashed with Benedict Arnold, and played a large role in souring him to the revolution. Their priority? Shoring up power for themselves by using government authority to help friends and punish enemies. Funny, how that works. I digress.

John Calvin, the famous religious philosopher who invented many of the doctrines which ultimately bear his name, was called to Geneva to serve its religious needs post-Roman Catholicism. The most pertinent detail of his biographical background is his extensive study of law prior to his religious conversion.

When Calvin came to Geneva, he introduced many basic Protestant doctrines. A core Protestant doctrine is that one is saved from sin through faith and grace alone. This is what allows Protestantism to reject the authority of the Roman Church, since it says that priests and sacraments are unnecessary. Well, the libertines of Geneva – chafing under Calvin’s other general moral teachings – began to exploit these teachings. They declared themselves “saints”. Why, through faith they were saved, so they would go ahead and sin anyway.

The libertine movement weakened Calvin’s position, and he was simultaneously prosecuted by renegades and began to run afoul of authority for his failings as a moral leader. It seems that the reason why the city authorities wanted a man like Calvin around was to restore moral norms to the common people, to promote authority.

Here we see the paradox of moral norms that post-modernism ignores. Yes, moral norms here are used to repress and control. Yes, to the benefit of the ruling wealthy class. However, if a city is full of disease, orphans, theft, violence, and chaos – while that does go against the interests of the rulers – it would probably also not be a very pleasant place to live. The people who reject moral norms enjoy their pleasures, but after many of them contract sexual diseases and create orphans, become drunks, and so forth: almost everyone laments those negative outcomes. Moral libertines aren’t necessarily thinking ahead when they act on their passions. Indeed this is the entire basis for the modern concept of “public health education”. Supposedly there are people out there who don’t realize at all that unsafe sex does have some risks (I’m being facetious, but actually it’s true that often people are unaware of the consequences of their behaviors and do later regret them, despite confidently bucking taboos initially).

Regardless, Calvin’s entire purpose was frustrated by these libertines. Christianity was supposed to be a moral paradigm which convinced people to behave well. Here, the Protestant doctrine which overthrew the Roman Church was being used to overthrow the whole Christian religion, and morality itself.

Calvin’s doctrinal response to this development might be considered cynical. However, I blame his lawyer’s training for pinpointing very the clause and letter which would settle this matter conclusively.

Calvin began to teach a doctrine called predestination. Yes, he argued, faith is how man is saved. However, the question of who truly has faith or not is settled by God before birth. A man is either saved or damned, by God’s incomprehensible will, before man is ever born.

It might seem like Calvin’s doctrine doesn’t settle the question. This is rather complex, but I’ll discuss some theological premises. If you are Catholic or Calvinistic, sorry, I’m not critiquing your beliefs per se. I’m referring exclusively to political consequences of ideological paradigms. However you understand your doctrines spiritually is not my concern.

Around just before Rome fell, its major religion was a much more varied Christianity than the one we know today. Orthodoxy had not at all been settled upon, and there were competing notions within the faith (although the Roman Church spent a millennium destroying and altering evidence to create the impression of consistent orthodoxy). One major point of contention (we are before the era of “schisms”) was over the question of sin and human agency.

Christianity says that man sins, but God’s grace through Christ saves. Instead of dying, maybe going to hell, man can live forever in paradise. Sin is the obstacle. Sin is immoral acts, which are disobedient respective to God’s commands.

In ancient times there was a question: since sin means disobeying God, and man’s guilt comes through sinning, doesn’t that imply man has an alternative of not sinning? If God gives a command, doesn’t it mean that man could choose to obey it? Moreover, though perhaps very unlikely, is it technically possible for a man to go through life without ever sinning? In other words, should Christians actively try to not sin, or is it hopeless, and instead man should just go to church and get saved automatically there.

A faction led by one “Pelagius” argued that Christ’s salvation empowers moral agency. By covering our mistakes, Christ makes it worth our time to try to be good people. If we are, like, 98% good, thanks to solid effort, then we’ll be alright even if we screw up a little. Thus, Christians must try to be morally good.

In contrast, Augustine argued that man is born with sin (this original sin doctrine thus officially appearing hundreds of years after Christ), and so we can’t really try to be morally good or not. It is through the church and its sacraments than man is saved, and the authority of its priests.

Another issue relevant to this argument was a controversy over whether lousy, sinful, hypocrite priests should be defrocked, or be allowed to stay in authority. Naturally, many argued that sinning priests were unworthy of their station. The official doctrine which emerged, of course, let sinful priests keep their positions.

What matters about Augustine’s debate with Pelagius, politically, is that it coincided with the shift within Roman civilization from classical urban living to feudal country living. Augustine provided the ideological basis which subjugated serfs to their feudal lords. It created a “natural order” in which human agency is dissolved, and peasants are born meant to fulfill a role assigned to them by God, and wait out mortal toil for the promised paradise. They didn’t have to be good people, exactly, they just had to stay in their roles. If they sinned, come confess, and go back to being a loyal peasant.

Thus, the doctrine of sin within creedal Christianity was used in conjunction with political subjugation and conformity to social expectations.

With Protestantism, those social expectations were overthrown. The bishop was kicked out. Merchant classes ascended to power. People became uppity.

John Calvin invented a perfect legalistic buffer to rising disorder.

Catholicism, through Augustine, robbed man of much of his agency. Nevertheless, there was still some agency which remained: the choice to fulfill one’s assigned social role or not. Catholic rule wasn’t absolute, but it did work to preserve broad social structures and the order they provided.

With Calvinism, the moral authority of the municipal council had to be established. Christianity already disassociated sin and salvation from human agency. None of your discrete actions would correlate to your soul’s status. Salvation came because of power structures which were bigger than you. But Protestantism overthrew these.

Would Calvin restore man’s moral agency? Of course not! How can the city conscript soldiers in that context?

Instead, Calvin said that man has absolutely no control over his own salvation, and moreover many if not most men are doomed to burn in hell eternally.

Calvin’s system introduced a key feature: doubt (only an evil genius lawyer mind could arrive here). Suddenly, man could not be assured of his own salvation. Thus, he was plunged into a perpetual state of fear, and an absolute lack of agency.

This was legally brilliant because it gave the state absolute moral authority. The trick was that, although in this doctrine people were not capable of moral agency, they were still required to be moral. It was still a religious requirement for people to follow moral and religious law. Some people, by virtue of God’s incomprehensible will, would be blessed to be righteous enough to consistently follow that law. Others, the majority, would inevitably sin. Thus, the duty of the righteous was to enforce moral law upon the unrighteous.

The legal brilliance comes from the fact that no one knows if they are among the elect, the chosen righteous, or not. Disagree with the state’s moral judgments? Well, you’re probably unrighteous then, and will go to hell. But there’s no way to know, though, for sure. The risk, and uncertainty, associated with the prospect of eternal hellfire is enough to cause people to automatically squash their distrust of authority. Fear and doubt internally conspire to constrain independent thought.

If democracy is rule by the people, then this system takes the people – and their judgment – out of the equation. In Calvinism, only the law is reliable and constant. Only the law is valid. And the masters of the law: the legislators and lawyers, become absolute rulers. So we see how the English Parliament rose to power after the English Civil War (featuring a lot of Calvinists).

Calvinism creates a rule by righteousness. The human sense of right and wrong is conscripted into support for the ruling authority. Good people follow the law, bad people question it. Legislators and lawyers shouldn’t be thought of as wielding power (they do), instead they’re just among the elect seeking to instantiate God’s absolute truth. They aren’t masters of the law, but are meant to be thought of as servants. This hypocritical nonsense is the governing paradigm of America, not democracy.

In America, lawyers, bureaucrats, lieutenant colonels, company vice presidents, pastors, professors, and so forth, follow their moral duty faithfully. They promote a righteous national order. Why, to be against that national order is to prove oneself as unworthy of heaven. Democracy as a principle is irrelevant. “Democracy” is an intellectual paradigm deemed to be righteous. Thus, by being superficially democratic, America is built according to righteous principles. This righteousness, not democracy, is what justifies America.

I want to mention that I believe that this mentality, while behind modern (Wilsonian) America, was among a set of competing paradigms at the time of the early Republic. The other ideas – such as those of the Scottish and English Enlightenment – helped create the notion that democracy is important. Calvinism, responding to the normalization of democracy as an ideal, upheld it as a token of what all good people support and believe in.

Calvinism itself doesn’t require democracy. Only lawgivers and lawyers.

What about the leadership of the nation? Well, yes it’s possible for a leader to exercise unrighteous dominion. Of course, if this happened, all the righteous people would rise up and put a stop to it. God’s grace, you know! Thus, if you feel alone in questioning authority, if you’re abnormal, you’re a sinner. You have no other means by which to judge your own worthiness.

Just follow all the rules, and if not you fully deserve the punishment which will be given to you. Reformatories use harsh methods, in this paradigm, as a sort of test of worthiness. Similar to the Monty Python witch test (in which a person is spared the death penalty by first drowning to death in a river, a proof of innocence), punishment as reform spares the righteous who live their lives with sufficient fear. Fear of damnation is mimicked through fear of pain and punishment. Reform is not a Calvinistic concept, but demonstrating your pre-election to society is. Following the law to avoid pain is proof of a worthy heart. The punished aren’t worth a second thought, a worse fate awaits them in the afterlife. Punishing the unworthy might discover that a few of them are secretly righteous. This is reform. In secular terms, the idea is to allow freedom of action only to those who prove capable of self-policing.

Calvinism, I believe, is the precursor to modernism. I can understand, therefore, why post-modernists would attack moral norms and “normalness”. However, I would like to call attention to Calvinism itself as the problem, and not norms as such.

The problem with Calvinism goes back to Augustine. Pelagian Christianity (the pre-Augustinian Christianity as we can infer, and not the slanderous caricature in the Catholic Encyclopedia), as a secular metaphor, suggests that God’s grace exists to empower moral agency. Original sin does not apply to individuals – Pelagian Christianity suggests that Christ’s grace cleanses original sin. Thus man is responsible only for personal sin, in direct proportion to that sin.

In this form of Christianity, sin is dealt with very pragmatically. Can recompense be made? Can a wrong be repaid, with interest if possible? Can guilt empower a person to modify their behavior? To turn away from sin is to be cleansed of its effects, metaphorically. This is not a moral paradigm that’s very conducive to state authority. In this paradigm, the state is morally equal to its subjects (and can hardly endure as a consequence).

Thus, using these religious metaphors, we can see how morality can exist outside of the Calvinist or Catholic paradigms. One moment in history in which some believing Christians challenged Calvinism strongly was during the 18th and early 19th centuries in New England.

William Ellery Channing argued against Calvinism. His argument was a moral one. He argued that Calvinism proposed a cruel God in light of human experience and human moral choices. To damn someone without them having any ability to affect the outcome is judged unjust and cruel. Calvinists responded that God’s ways are beyond our comprehension. Channing argued that, while ultimate truth might be incomprehensible, certain discrete aspect of God must be knowable.

Channing argued that almost all proofs of God rely on internal evidence. Something pertaining the nature of man causes him to perceive righteousness as righteousness, and goodness as goodness. If God is the creator, this something must be God’s will for man’s nature. Thus, for God to provide man with a sense that cause man to see God as fundamentally cruel – due to predestination – then it means that God is inconsistent.

Pointing to this inconsistency, Channing says that simple moral reasoning easily disproves Calvinist doctrine. It would not be possible for God to predestine souls to hell, such a being could not be the same one which created us with notions of itself.

What Channing did, theologically and metaphorically, is restore man’s agency. The existence of the perception of right and wrong implies, fundamentally, the ability of man to judge rightness and wrongness. To clarify the metaphor, it is similar to Hoppe’s argumentation ethics.

When a post-modernist chides moral repression, he is making a judgment. The invocation of judgment implies the appropriateness of judgment itself. If judgment exists and is appropriate, then we can’t criticize the process of judgment, only particular contents of particular judgments.

Foucault said that the concept of “man” was invented in the 19th century. I think we always had it implicitly. Catholic theology created a political order which tried to impose a convenient ideology which treated humans as cattle of a sort, sheep to be shepherded. They personally don’t really need to bother reading the Bible, or knowing the finer nuances of church doctrine. Salvation was an effect which applied to them, not something they had to figure out for themselves.

As a Romanian Orthodox priest once yelled in my ear during my mission there back in my Mormon days, “If you are born Orthodox, you are Orthodox.”

What about the faith of the leper, which caused him to be healed by Christ’s power in a famous Bible tale? I suppose Calvin would say he was born into having that faith.

As for me, I think the existence of the story at all declares for human moral agency. Why know about faith, if it’s not a meaningful alternative, subject to choice? The purpose of such tales is to convince us to exercise moral agency. Christianity was meant as a religion to empower moral choice. Christ is the God who valued moral rectitude over His own life, who eschewed the lofty throne, for the morally sound one.

Man was always there, and the church had to bend and twist man out of shape to desperately obscure that fact. The idea of man wasn’t invented in the 19th century, it was reclaimed from the powerful, who hated it.

Still, referencing Foucault, the ideology of Calvinism traps us in a labyrinth of ideas. Our choices are framed by a notion of the normal and abnormal, and our social frame causes us to direct our choices in a way that’s suitable to power.

I personally think choice exists, it’s a thing. I think choice always exists. What Calvinistic politics does is cause us to self-police so that we choose to frame our choices according to the predominant social paradigm. We choose to narrow our moral thinking, because we fear the real consequences of not doing so. But this is still a choice, and exists in a context where the alternative is always available.

How should we handle morality then?

The principle which I defend as central to the discussion of morality and social norms, I call “free moral reasoning”. This is the social and political validation of individual judgment in weighing evidence and coming to conclusions. Another name for this phenomenon is: the conscience.

In Christian terms, one would say that God permits man to choose to sin, only because God desires for man to make moral judgments, and moral choices freely.

Along with free moral reasoning, I support the importance of the principle which I call free moral agency. One’s moral reasoning is worthless if it cannot extend to one’s choices. Where choices and actions don’t impose on others, an individual must be free to act according to their conscience.

Freedom of conscience is the core principle associated with what I have called the “social non-aggression principle”. Freedom of action is, in parallel, key to the political non-aggression principle.

How does free moral reasoning work, functionally?

The main difference between traditional, Calvinist, morality, and social mores which result from a culture of free moral reasoning, lies with the difference between negative and positive mores.

A negative moral proscription tells you what you cannot do: “Don’t do drugs, they are not allowed.”

A positive moral prescription tells you what is good to do: “Life is richer when you have a broad awareness of, and sensitivity to, your sense of meaning and purpose. Drugs can sometimes inhibit that sensitivity, so avoiding them is something to consider.”

In this paradigm, moral reasoning is sacrosanct. It would be socially taboo to shut down someone’s moral reasoning. Instead, moral dialogue occurs by engaging someone else’s moral process.

You could not say: “You’re a boy who wants to wear a dress? I don’t want to hear it, you’re a nutcase, don’t come near my kids.”

You could say: “Boys wearing dresses is not conventional, what makes you want to break that convention? Some transsexual women might pose a safety risk to my daughter, if they share her bathroom; can you address my concern?”

In the case of both the transsexual woman, and the concerned father, each one’s concerns are valid by virtue of existing. Neither can invalidate the concerns of the other. The father can’t simply deny the woman’s desire to transition from being originally male. The woman cannot deny the father’s concerns as mere bigotry. The woman has the right to have her desires validated, and the father the right to advance his concerns. One deals with each point of view by engaging with its internal reasoning.

At some point, engagement with reasoning will reach a dead end. Many people believe things that aren’t quite rational. Emotion governs a lot of human behavior. That’s okay. What matters is that the boundaries of a moral belief must be discovered. Anyone who has a belief or stance has to at least present some rationale. Every moral renegade has to at least attempt to justify themselves.

Abdication of moral reasoning is an automatic invalidation of a moral position. I would argue it’s not right to invalidate a conclusion of moral reasoning, but I cannot validate the rejection of moral reasoning altogether.

As I argued elsewhere, if pure postmodernism is right, then what’s wrong with Hitler? What’s wrong with repression and oppression. Maybe the oppressors believe in what they are doing? In the end, might will make right. So, postmodernism does in fact draw veiled moral conclusions of a certain sort about right and wrong. Postmodernism rejects repression and oppression as negatives.

Clear and open moral reasoning is better for everyone. As long as a moral renegade makes the effort to present a consistent rationale for their behavior, then clear boundaries of disagreement can be discovered.

The value of moral boundaries (as I describe them here) becomes clear in Thaddeus Russell’s Renegade History. Prostitution, totally illicit, led to a market for the somewhat illicit condom industry. While society might have had more of a stomach for condoms (used by married couples presumably) than prostitutes, it was nevertheless unable to create a market for them. It was the complete bucking of mores by the whores which made room for the acceptance of birth control. This occurred naturally, but it could have occurred deliberately. The condoms lay somewhere on the boundary between two moral paradigms.

Morality exists to provide social order which eliminates negative consequences of certain social behaviors. As I’ve said, many of these outcomes represent – merely – modes of control for the benefit of the ruling elite. However, many mores also provide a means of eliminating genuine negative outcomes. There becomes a paradox involving self-repression and personal loss of liberty, in exchange for a positive social outcome.

The paradox which contrasts personal freedom against social well-being happens to also be a fulcrum which defines the difference between contemporary left-wing and right-wing philosophies. Left-wing politics suggests that personal desire, unmanaged, will produce negative social outcomes; according to this ideology, personal freedom must be limited. Right-wing politics (in contemporary America) suggest that the effort to manage social outcomes produces worse results through repression, than whatever positive social benefits emerge.

This whole discussion can be simplified if society has a clear sense of having a deliberate moral dialogue. Pro and anti drug factions (not speaking of prohibition, but those who advocate drug use and those who argue against it) can have a dialogue. Why would drugs be harmful, specifically? Where are these concerns meaningful, and where are they too broad a brush? If drugs can be consumed safely, in many cases, how would you know once you’ve gone too far? This is a discussion, which can involve reasoning, evidence, and objective discussion. It can also involve subjective preference. A thorough discussion, free of the threat of punishment for violating taboos, open to new evidence, can discover the places where people have to “agree to disagree”.

If I’m against drug use, and someone else is for it, I might discover a boundary. If a methhead runs down the street in front of my house slashing tires, or blows up the house next to mine, and so forth, these cases would represent examples of where “agreeing to disagree” doesn’t work.

So what if my house gets set aflame due to meth use? Well, is the use of meth the cause of my house burning down, or is negligent chemical production the cause? So here is where the boundary is – the action of mixing chemicals in proximity to my property without demonstrating safety precautions. I can make an issue of that. Otherwise, I’m just asserting my moral preference on someone else, which would be inappropriate.

This issue becomes more complex. What about if my daughter goes to a high school where many people are using meth? Psychological science shows that many people who would not prefer the negative consequences of meth consumption, might not keep those consequences in mind when they start using – especially with adolescent brains, not fully developed. While that might be “their problem”, what if I identify a social-psychological phenomenon by which the high of meth, and the social pressure to try it, would usually overpower the reasoning abilities of group of young people? What could I do if I felt that my daughter would not be safe in that environment, from meth’s negative consequences, no matter how well I raised her?

I could make a rationally sound judgment that many social circles which involve or permit meth use, are overly risky. I’m not telling these people that their behavior is “not allowed”. I’m saying that their environment exceeds my risk preferences for my own daughter. I would use that language in dealing with the situation.

“Daughter, don’t get involved with that group. They are taking too many risks.”

How to raise a child is a completely separate discussion. What matters here is that I would not call the drug users “bad”. I’m judging them as “risky” and too risky for my preferences as a father.

Thaddeus Russell, in his book, talks about young women and their resistance of repressive mores. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that sexual mores are completely bad. I think modern society has a big socio-sexual problem. People are unhappy. Women who might prefer more commitment for less sex, are forced to give more sex for less commitment – just to attract sexual partners at all. Many men are shut out of sexuality altogether because of the frenetic competition women endure to attract the best males. Relationships built on sexual pair bonding have no socio-normative support to stabilize them through life’s shifting moods. Stable parenting situations are disappearing for the majority of newly born children in American society. I don’t think most people prefer these overall outcomes, but at the same time, no one wants to be sexually repressed.

I won’t argue that America’s Puritan sexual mores are good, either. By eschewing these mores, maybe America lost something, and maybe we gained something.

The genius of Thaddeus Russell is that he identifies something underlying, and transcending this question. Whatever you think about evolving sexual habits, the fact is that bucking strict Victorian mores led to much more than people having more sex. Women intent to freely play the mating game, following their passions, created a market for a certain kind of vice.

Coney Island – once a den of gambling – catered to the new vice of “fun”. These young women sought a way to express their repressed passions. I’m sure many of them chose to have sex. But holding hands and snuggling with your sweetheart on a Ferris Wheel, sharing a smooch in the tunnel of love: these activities were created by the resistance against social norms.

I’m not one to talk about the sexuality of children. When little kids ride Ferris Wheels, or feel thrills on dark rides like “Winnie the Pooh” at Disneyland, I don’t think it has a thing to do with sex. I think it’s just a case of them experiencing fun. For various reasons, Puritanical America opposed this kind of leisure.

Thus, although young women might not be doing themselves any service in their shameless pursuit to be the next girl for Mr. Popular to leave high and dry, their rebellion against the norms which restricted them led to something greater, which everyone benefits from.

Renegades do the heavy lifting when it comes to free moral agency.

I can play armchair philosopher, and discuss moral paradigms all day. I can pick apart language and how we talk about mores, and come up with dozens of examples. In the end, it’s not nuanced discussion that liberates people, it’s the people who buck taboos who do the hard work.

As someone who’s not a postmodernist, I believe that there is at least a little bit of human nature which is sort of something like “essential”. I do think that moral reasoning is something that most people naturally do most of the time. When a renegade bucks a taboo, somewhere inside themselves is at least a subconscious thought process by which they at least rationalize their action. I maintain that thought is something that people just do, it’s part of everyday action.

When a renegade bucks a taboo, they are advancing a competing moral paradigm. This is true even if they don’t realize it. A renegade can succeed or fail. Nevertheless, they do by action, what I have been trying to do here through words. The assert a different paradigm, society pushes back, the renegades push back again, and boundaries are discovered.

Society, and libertarians especially, should look to the renegades and thank them for making society free. Even moralists should thank renegades. Challenging extant moral norms refines them, makes them correspond more accurately to real conditions. If morality is meant to provide social harmony and positive social outcomes, then renegades are to thank for paying the price which takes us closer to those objectives.

Nevertheless, the way renegade behavior has been dealt with historically is not ideal. Calvinist repression has been harsh and cruel, and I certainly won’t defend it. However, am I saying that we should just let renegades do whatever they want? Of course not! I find the value of renegades to be the tension they create, the moral competition they promote. We can’t roll over to renegades, but we’re hurting everyone if we fight and prosecute them. So what’s the right way to deal with renegades?

First of all, we want moral standards. We should all have our own preferences, experiences, and reason to guide our sense of what’s moral or not. If we lack one leg of that triangle, we’re wrong. Pure reason isn’t enough. Preference without reason is decadent. Experience without reason is bigotry. Reason and preference without experience is sophomorism.

Second of all, we want renegades. When someone is pushing for new moral standards, we should value it. To fight for our one single moral paradigm against all critics is stagnant. Life, society, and civilization are not stagnant. We’re always evolving. Or moral paradigms need to evolve with us.

How do we reconcile these two priorities?

The answer is what I’ve said: positive morality. Don’t try and stop renegades, try to argue why your moral paradigm is better. Don’t squash their preferences, assert the value of yours.

Positive and negative power are present in politics. Negative power is when you shoot someone for not following the rules. Positive power is when people coordinate their behavior. Positive power is considered to be stronger. It’s costly to police a nation, and to force them to pay taxes when they don’t want to. When people believe in taxation, and pay it willingly and enthusiastically, then its much more profitable for the rulers.

Napoleon had legions of troops fighting for the “peoples’ nation” against the mercenaries of petty feudal lords, and he almost conquered all Europe. Positive power overruled negative power.

Positive mores could have a parallel vitality to positive power. Don’t fight renegades. If you disagree with them, stick to your own mores, and prove that they’re better.

Again, in Channing’s words: “We venerate not the loftiness of God’s throne, but the equity and goodness in which it is established.”

Morality can still govern society, but it must rule with love, and not with fear. Be moral, because you’ll love what it will do for the world you live in.

America’s free moral reasoning, positive morality, is going to be what the world needs to survive the massive social changes associated with the ongoing great global liberation from negative moral norms.

Renegades are the canaries, the touchstones. If morality can countenance renegades, then it’s good. If it cannot, then it’s harmful.

I hope Thaddeus Russell keeps fighting the fierce fight for alternative moral ideas. I like the fact that he fights for alternative ideas for their own sake. I hope, however, he transcends his fixation on pure Postmodernism. Foucault’s ideas are still relevant, but his ideology is harmful.

Postmodernism, like Calvinism, introduces doubt. Moral doubt is the basis for the absolute rule of absolute law.

America will survive the times by rejecting amorality, Postmodernism, but most of all, our Calvinist curse. Woven into our cultural, philosophical tapestry is a zealous moralism. Good! Let’s evangelize this principle of individual empowerment. Let’s have America remain a project for good in the world, let’s be worthy of that notion which is America’s ancient identity.

Let’s discard America’s mace of law, and replace it with a beacon of faith. Let’s replace our fear with love. Let’s chuck this empire over the Earth out the door, and concern ourselves each with the moral empire we build over our own minds.

As for me, this is my clear identity. I’m not white, or German, or Scots-Anglish, or a flag waving patriot. Neither Paul Revere, nor G.I. Joe, nor apple pie have a thing to do with my identity. My legacy, and heritage, as far as I care to acknowledge it, is as an ambassador of the mind and soul’s freedom to all the world. To the United States as much as to anywhere else.

Thanks to intellectual renegades, I’ve learned that I need to shed the Calvinism in my soul. To let go of a need to control outcomes.

Still, despite all the intellectualizing of this issue I’ve done, real freedom – and real morality – will come through the actions and striving of moral renegades. Free moral reasoning means the competition of moral ideas. That can’t occur without people willing to enter into the ring, and get bloodied.

Thank you, renegades, morality depends on you.