For the first thirty years of the twentieth century, when there was trouble on the peripheries of the emerging U.S. empire in the form of rebellions, bandits, or resistence, Washington could always rely on one soldier to restore order. Invariably, days after his appearance, newspapers nationwide would carry the identical headline, “The Marines arrived and everything is quiet.”

So how did it happen that, after three decades as a reliable hatchetman, this soldier turned and took aim at the same military, financial, and political leaders whom he had served?

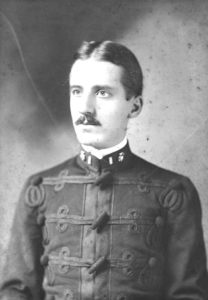

Smedley Darlington Butler was born 140 years ago to the day in West Chester, Pennsylvania, a descendent of the prominent Darlington family of Quakers and the son of Congressman Thomas S. Butler, future Chairman of the House Naval Affairs Committee.

When the United States declared war on Spain in April 1898, the sixteen year old attempted to enlist and was denied because of his youth—his congressman father went so far as to have his name blacklisted among local recruiting stations. Bucking paternal coddling, Butler fled the coop and successfully enlisted in the Marine Corps as a Second Lieutenant by falsely giving the birthdate of his older brother.

When the United States declared war on Spain in April 1898, the sixteen year old attempted to enlist and was denied because of his youth—his congressman father went so far as to have his name blacklisted among local recruiting stations. Bucking paternal coddling, Butler fled the coop and successfully enlisted in the Marine Corps as a Second Lieutenant by falsely giving the birthdate of his older brother.

The spotlight shone on him as soon as he landed at Guantanamo Bay. His reckless courage garnered the attention of Theodore Roosevelt, then commander of the Rough Riders in Cuba. The future president called the young Marine “the ideal American soldier,” simply “the finest fighting man in the armed forces.” Supporters would positively compare Smedley to TR for the rest of his life.

What followed in short order were deployments to the Philippines, China (where Butler was wounded during the Boxer Rebellion), and Honduras. Briefly returning stateside, he married Ethel C. Peters, the daughter of a wealthy railroad executive with whom he would have three children. Joined by his young bride, Butler would return to the Philippines before spending the turn of the decade leading a Marine battalion into battles in Panama and Nicaragua.

In 1914, during President Woodrow Wilson’s intervention in the Mexican Civil War, Major Butler found himself stationed with a battleship squadron off the coast of Veracruz. In coordination with his commanding officer, Butler donned civilian clothes and sneaked to shore. Once in Mexico City, the Marine posed as various alter egos (including a railroad employee, private investigator, and geologist), bluffing his way into inspecting Meixcan troop arrangements before returning to the fleet with vital information. If his disguise had been discovered at any time, he would have been promptly shot as a spy.

The next year, during the American pacification of Haiti, Butler led a storming party of Marines at the Battle of Fort Rivière, scaling a 300-foot embankment before he and two other men crawled through a drain pipe to capture the stronghold from the dozens of rebels inside. He remained in-country for a time to organize and command the Gendarmerie, the enforcement arm of the U.S. occupation (which would continue until 1934).

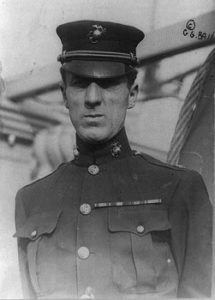

When the United States entered World War I, Butler was deployed to France—not as a fighter, surprisingly, but as an administrator. Promoted to Brigadier General in October 1918, he was placed in charge of the demarcation depot at Brest, the gateway for the U.S. Expeditionary Force. “Thin and wire-tough, with a raptor’s nose and a glare so fierce his men called him ‘Old Gimlet Eye,’” historian Geoffrey C. Ward describes it, Butler transformed the camp from a sea of mud into an orderly way station in a matter of weeks.

After the war, as Commandant of the Marine barracks at Quantico, Butler “had a reputation for blunt, honest talk, complete honesty, impatience, and an insistence on discipline,” writes historian Ellen C. Leichtman. This no-nonsense notoriety led the mayor of Philadelphia to request that General Butler be sent on “loan” from the corps to take control of the city’s police force and sweep away the crime and corruption that had become rampant during Prohibition.

In January 1924 Smedley Butler was sworn in (wearing his Marine uniform) as the Director of Public Safety in Philadelphia. Within one week he and his police raids had shut down or destroyed 973 out of a reported 1,200 underground saloons and speakeasies in the city. “Whether a law is right or wrong, all law has got to be enforced. And if you do not want law enforced, do not call upon a Marine to help you out,” Butler said. When his leave of absence expired in December 1925, the mayor and the city’s social elite (whose Ritz-Carlton booze parties Butler had crashed) were happy to see him leave.

The maverick Marine’s career in his beloved corps ended less than fortuitously. After spending another year in China (not so much a soldier as a consummate diplomat), he was promoted to Major General in 1929 just shy of 48 years old. But when there was an opening for Commandant of the Marines, the highest position in the branch, Butler was snubbed in favor of someone with more seniority but less experience.

Shortly after being passed over, Butler caused an international incident when, giving an address at a club in Philadelphia, he recounted a story of Benito Mussolini being a hit-and-run driver, speeding over a child and continuing on his way. The Italian embassy lodged a formal complaint. Il Duce received an apology from the U.S. government, and Smedley Butler received a court-martial (immediately dropped due to public outrage in favor of a reprimand). In the aftermath, Mussolini’s passenger, Cornelius Vanderbilt Jr., authenticated the chilling story.

Smedley Butler retired from the service on October 1, 1931. In his thirty-three year career he had come under enemy fire in 130 distinct engagements, and with the exception of his daughter’s wedding, would never wear his dress blue uniform again.

From dodging bullets to harvesting ballots, it was only a matter of months before he attempted an entry into politics. In March 1932, acting as a stand-in for Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot (“I am for Smedley D. Butler because he is Smedley D. Butler”) the restored civilian announced a primary challenge to incumbent Senator James “Puddler Jim” Davis.

“The paramount issue today is not whether Pennsylvanians shall drink but whether they shall eat,” Butler shouted at a rally in Pittsburgh. The voters, however, disgusted with Prohibition, disagreed. Butler lost thousands of potential supporters by adhering to a “Dry” platform and the “Wet” but otherwise noncommittal Puddler Jim sailed to renomination—including a five-to-one margin in Philadelphia.

The total cost of his senate campaign was $800, the equivalent of $14,000 today.

After what he referred to as his “big drubbing,” Smedley Butler spent the rest of the year continuing to focus on those undercut by the Great Depression. Promising to do anything to alleviate their situation, “even to parading in my underclothes,” he raised money for the unemployed. When thousands of veterans marched on Washington DC demanding early dispensation of their military bonuses, Butler spoke to and encouraged them, while more famous generals like Douglas MacArthur and George Patton participated in the bulldozing of their makeshift camps.

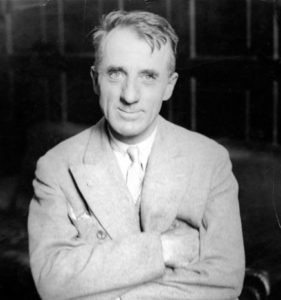

The retired general burst into the national headlines in November 1934 when he alleged that Wall Street financiers, frustrated by the New Deal policies of the Roosevelt administration, offered him three million dollars to lead an army of 500,000 veterans to the capital and overthrow FDR in a coup d’état. Widely dismissed as a hoax in the press, a congressional committee that heard Butler’s testimony was able to corroborate the core of his accusations, although it declined to pursue them due to the wide gap between the plotter’s contemplation and execution.

Reporter Heywood Broun, whose syndicated column was more than naught dismissive of Butler as a headline chaser, is probably fairest in his description of the Business Plot. “I haven’t the slightest doubt that Smedley Butler heard many captains, or at least second lieutenants, of finance talk in terms of millions of dollars and half-million armies to save America from Tugwell and taxes,” wrote Broun. “As an old devotee of free speech let me admit that even the owners of finance and industry have a right to shoot off their faces.”

When originally asked what he would do upon his retirement in 1931, Butler said, “I’ll take to the lecture platform. And I’ll talk about anything I please. There won’t be any muzzle on me then.”

The focal point of these speeches was the deconstruction of his own military career and how U.S. foreign policy had been captured by Wall Street and the burgeoning arms industry. In Butler’s words, when he was leading Marines into Mexico, the Carribean, and China he was acting as “a gangster for capitalism.” He elucidated these thoughts in his 1935 book War Is a Racket. He implored his countrymen to focus on home and hearth, not profit and adventurism;

Think it over, my dear fellow Americans. Can’t we be satisfied with defending our own homes, our own women, our own children? Right here in America? There are only two reasons why you should ever be asked to give your youngsters. One is defense of our homes. The other is the defense of our Bill of Rights and particularly the right to worship God as we see fit. Every other reason advanced for the murder of young men is a racket, pure and simple.

Lamenting the “men who were the pick of the nation eighteen years ago” but who now reside in military hospitals as “the living dead,” Butler called for more democratic participation in foreign policy, particularly by soldiers. He said the Secretary of State should be required to read all diplomatic correspondence over the radio to preclude secret commitments, and that there should be a national referendum prior to a declaration of war.

Originally a progressive Republican during his 1932 senate bid, Butler’s politics grew more radical over the course of the decade. Having previously voted for Roosevelt that November, in 1936 he instead cast his ballot for socialist Norman Thomas (although Thomas disregarded the existence of the “Business Plot”). When Louisiana demagogue and prospective presidential candidate Huey Long, father of the economically populist “Share Our Wealth” program, promised to make Smedley Butler his Secretary of War, Butler called it “the greatest compliment ever paid me.” Long was assassinated in September 1935.

The outbreak of war in Europe did not change his tune. On September 1, 1939, the day Nazi Germany invaded Poland, Butler published an op-ed in the The Gazette of Cedar Rapids, Iowa asking Americans, “Will you be any happier if Poland should reappear as an independent country and your boy is buried in an unknown grave?”

“Listen, you birds, it’s the same old racket,” he told an assembled group of Knoxville businessmen in January 1940. Roaring and joking, Butler promised them that should Adolf Hitler ever land an army in Mexico, “they would find walking wasn’t so good through Texas where there are ten million wildcats to claw them.”

Unfortunately, Smedley Butler would never be given the opportunity to claw Nazis himself. Prematurely exhausted by constant travel and rapid weight loss, he died at the Philadelphia Naval Hospital on June 21, 1940, presumably from cancer. He was 58 years old.

“Such characters as Smedley Butler sometimes enliven the action in public life when it gets stale,” eulogized one newspaper in Bloomington, Illinois. One hundred and forty years after his birth, there remains no modern equivalent to the heroic, outspoken, and quintessentially independent apostate general.

Today his earthly remains reside in his hometown of West Chester, less than an hour outside Philadelphia, under an unusually nondescript headstone for someone who led such a varied life. Today, in person or remote, pay your respects and wish a happy birthday to a fearlessly honest soldier and a thoroughgoing American.