The period 2003-2018 saw Washington annually spending hundreds of millions to tens of billions of dollars supporting regimes across the Middle East and North Africa. While some of the effects and outcomes of these “investments” are obvious, such as the lost wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the destruction of Libya, near destruction of Syria, and the rise of ISIS to name just a few, other outcomes and relationships are less readily apparent. Using a combination of the U.S. government’s own records of foreign aid contributions to each state in North Africa and the Middle East, and metrics calculating the relative protections accorded political rights and civil liberties in those same states, this statistical analysis focuses on the relationships, or lack of relationships, between these primary variables.

Below is a summary of its key findings:

- First, changes in the amount of U.S. aid given had no statistically significant relationship with whether regimes backslid or improved in terms of protecting the civil liberties of their populations.

- Second, changes in the amount of U.S. aid given had no statistically significant relationship with whether regimes backslid or improved in terms of protecting the political rights of their populations.

- Third, similarly, there was no statistically significant relationship between a regime’s improvement or backsliding in the protection of the civil liberties of their populations and the amount of U.S. aid that regime received.

- Fourth, similarly, there was no statistically significant relationship between a regime’s improvement or backsliding in the protecting of the political rights of their populations and the amount of U.S. aid that regime received.

- Finally, how much aid was dispersed, and which states received it, had no statistically significant relationship with whether or not a Democrat or Republican was in the White House.

The dataset utilized for the series of fixed effects (fe) panel regression analyses comprising this study was created by the author using the United States Agency for International Aid and Development (USAID) Greenbook data for U.S. government transfers to the states of North Africa and the Middle East for the years 2003-2018; while for those states’ political rights and civil liberties scores, the author used the annual “Freedom in the World” country by country report published by Freedom House. That report ranks the relative political rights and civil liberties in each state on a 1-7 scale, with lower numbers associated with more political freedom and better protections for civil rights. Lastly, other variables utilized over the course of the analyses included binary variables for which party controls the White House (1 for Republican, 0 for Democrat), whether the state receiving foreign aid experienced a military coup (1 for coup, 0 for no-coup), or whether there was serious civil unrest in a given country (1 for unrest, 0 for no-unrest).1Dataset and Log-File available upon request.

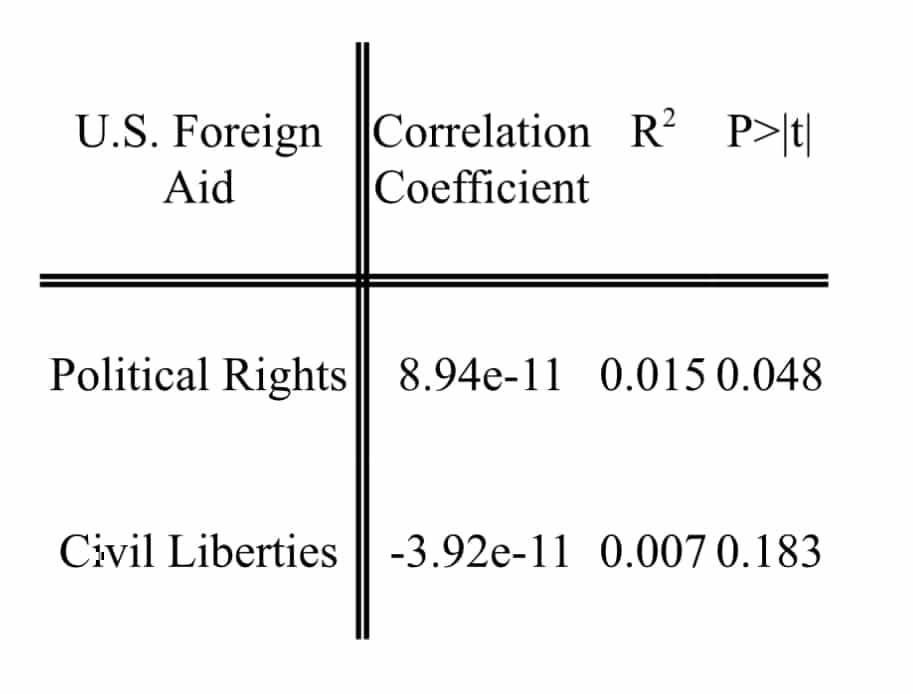

U.S. foreign aid programs, managed by organizations like USAID and supported by the U.S. State Department, aim to promote American values such as political freedom, civil liberties, democracy, and human rights across the globe. By providing assistance in various forms, including development aid, capacity-building, and humanitarian assistance, the United States claims to seek the strengthening of democratic institutions, support of civil society, and empowerment of individuals, thereby contributing to a more stable and prosperous world in line with alleged U.S. values. The first battery of tests put these goals under the statistical microscope; regressing U.S. aid by country with the annual fluctuations in its Freedom House scores for political rights and civil liberties for the years 2003-2018, the results are as follows:

While it is immediately obvious that the likely impact of U.S. aid on civil liberties in a recipient country is negligible, with the p-value failing to clear the standard 5% threshold, the within r-squared value suggesting less than 1% of the variation in the dependent variable (civil liberties) is explained by the independent variable (U.S. aid), and the correlation coefficient representing a number vanishingly small, it is less obvious that U.S. aid’s relationship with changes in the political rights enjoyed in a given country is equally lacking.

While mathematically insignificant in any case, the correlation coefficient again representing a number vanishingly small, the p-value does clear the technical level of statistical significance at .048. However, once the regression is run sans Israel, whose Freedom House scores might be reasonably be argued to be overgenerous given its treatment of the indigenous Palestinian population, it has after all now been officially referred to as “apartheid” by another major NGO, Amnesty International, in 2022, that indication of (slight) statistical significance vanishes, with the p-value corresponding to the subsequent regression rising to 0.052.

In summary, U.S. aid had no clear relationship with the protections of political or civil liberties in the observed recipient countries during the period in question.

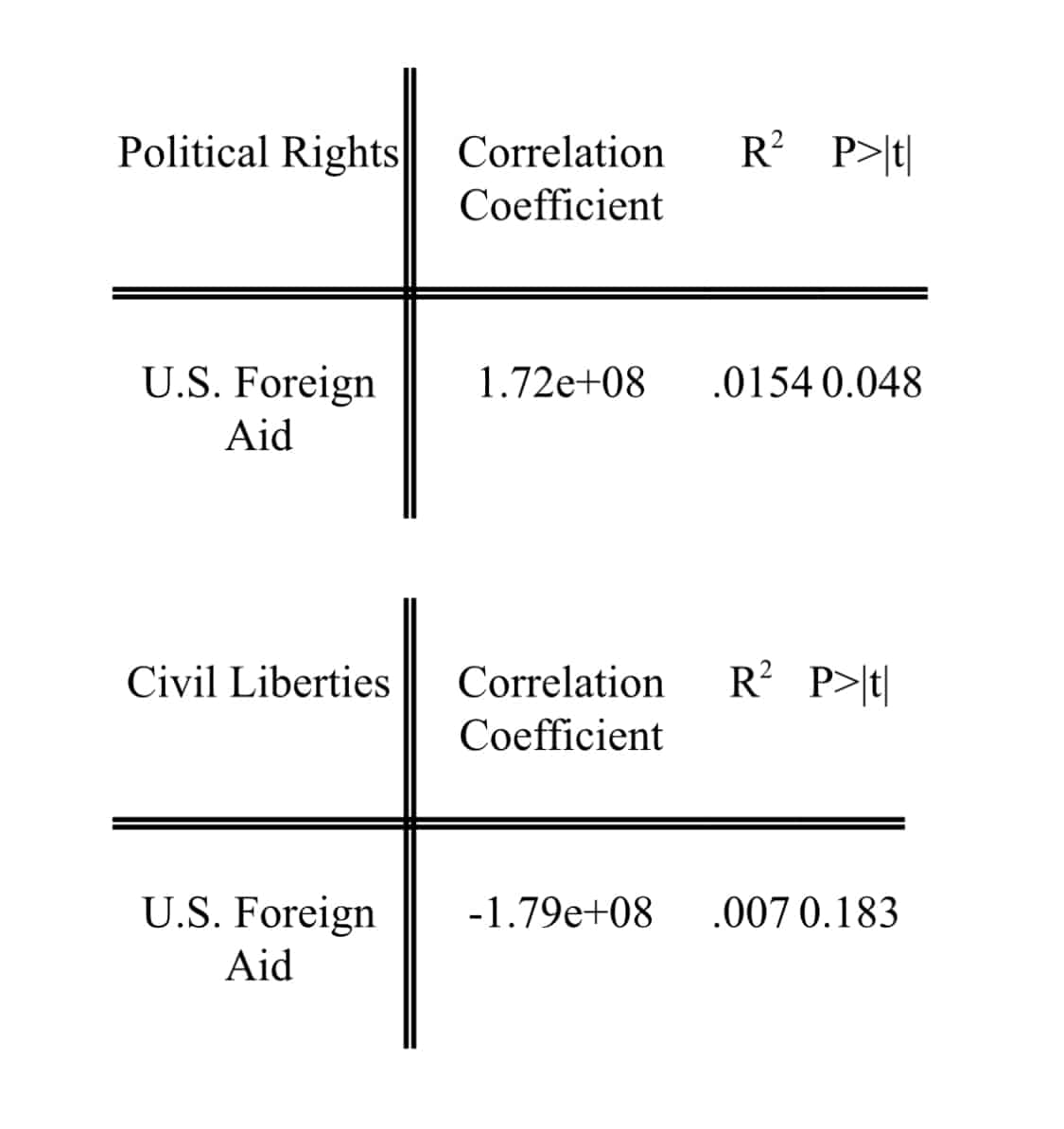

A related set of analyses reveals a similar set of dynamics at play with regards to how changes, positive or negative, in a country’s civil liberties or political rights scores related to changes in the U.S. aid that state received:

Again, while the lack of a statistically significant relationship between a country’s civil liberties score and the amount of U.S. aid received is clear, the lack of a statistically significant relationship between its political rights score and the amount of U.S. aid received is less clearly irrelevant. Once Israel is excepted, however, the p-value of the corresponding regression rises to .052, with a similar r-squared, 0.0157, suggesting that much of what drives the amount of aid given to the states in the sample is explained by unobserved individual characteristics specific to those individual states—and is not in response to changes in the relative protections accorded political rights and civil liberties by a given recipient. For while $172,000,000 is a substantial number, its consideration within the wider context of the other hundreds of millions and billions spent over the decade and half, 2003-2018, in the variety of regimes that received those sums, strongly suggests a country’s political rights score played only the most peripheral role in such considerations.

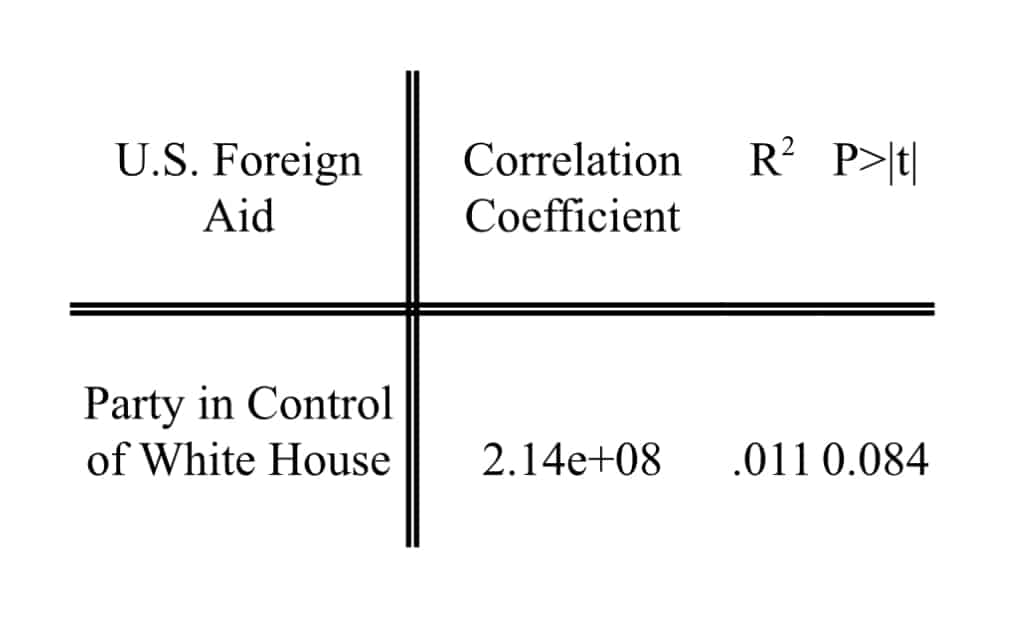

Finally, analyzing the binary variable “Party in Control of White House” reveals no statistically significant relationship between the level of aid given and whether a Democrat or Republican was in control of the White House, with the p-value failing to reach the 5% level of significance and the r-squared value suggesting scarcely 1% of the variation in the dependent variable is explained by the value of the independent variable:

It is worth noting here that, as elsewhere above, the intercept term suggests marginal significance. That is, the intercept is routinely observed to meet the level of statistical significance across the above tests, which suggests, according to the model, that some baseline level of aid would flow to the states of North Africa and the Middle East even were all of their civil liberties and political rights scores to be absolute rock bottom (indicated by a score of “7” per the old Freedom House metrical system).

In short, U.S. aid flowed no matter who was in the White House, whether or not a state respected the political rights or civil liberties of its population, and U.S. aid had no statistically significant effect on whether respect for the political rights and civil liberties of a recipient country’s population increased or decreased.

Despite its proclaimed intention to help promote American values such as political freedom, civil liberties, democracy, and human rights, U.S. aid accomplished little toward achieving those ends in North Africa and the Middle East, from 2003-2018. While one is always free to question Freedom House’s scores, either on the grounds of individual country-level bias or on the basis of methodological disagreement, the results obtained by the above battery of rigorous testing should withstand most such criticisms. For example, even if one accepts Israel’s Freedom House scores as legitimate, as we have seen it changes little. So, too, controlling for the occurrence of military coups, as in Egypt, U.S. aid dips only temporarily before resuming its prior level. It seems clear on the basis of this analysis, then, that more realist logic dictates the allocating of the nearly $40 billion dollars in U.S. aid that annually flows out to regimes around the world. However, given just how bad Washington has proven at playing grand strategy, from handing Baghdad to some of Tehran’s closest friends in the region to turning Libya into an extremist breeding ground, to pushing Russia and China together, that rationale too should ring hollow.

End foreign aid.