What does it take to turn an ordinary person into a monster? To create a mass shooter, a terrorist, a Joker?

According to Joker himself, “One bad day.”

That’s how he tells his own story in Batman: The Killing Joke, a 1988 graphic novel by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland. This classic origin story heavily influenced the controversial new Joker film.

Once, Joker was an ordinary man. He was trying to be a good husband, preparing to be a father, and striving to make it as a stand-up comic. But his jokes were bombing and his family was trapped in poverty. He felt like a failure. He was overwhelmed by humiliation and guilt.

Then a criminal gang offered him a way out. If he helped them with just one crime, he’d be rich. Desperate to turn his life around, he accepted.

But then, the “one bad day” happened. On the day of the planned heist, his pregnant wife died in a freak accident. He tried to back out of the criminal scheme, but the gang wouldn’t let him. Then the heist went bad. Batman showed up. Trying to escape capture, the man jumped into a pool of toxic waste. He emerged looking like an insane clown. Then he started acting like one. And he never stopped.

One bad day broke him. One bad day drove him to madness and murder.

You can imagine what a day as bad as that would do to you. I’m guessing it wouldn’t turn you into a supervillain or a serial killer. But, it might lead to serious mental health problems. Maybe anxiety. Maybe depression. Maybe worse. For a few, a major life tragedy can drive them over the edge.

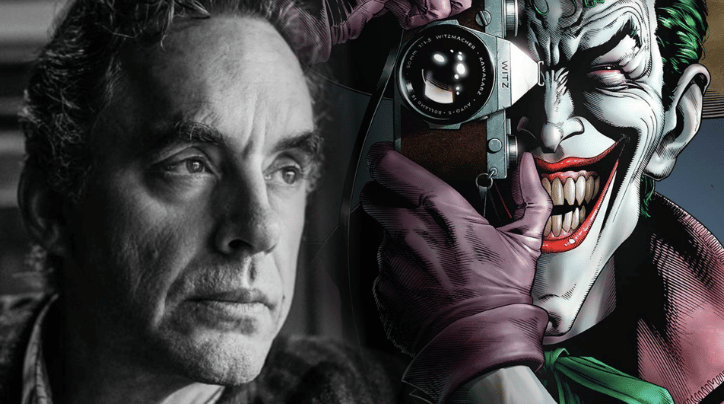

Joker, Meet JBP

This raises important real-life questions. What can we do in the face of tragedy? How can we reduce suffering? How can we prevent evil?

These are challenges that Dr. Jordan B. Peterson has thought about his whole life. Peterson is a clinical psychologist, a college professor, and a YouTube superstar. Many young people say his talks have changed their lives for the better.

He has also studied evil very deeply. He has read the diaries of school shooters and researched genocides and totalitarian dictators.

What if Jordan Peterson met Joker? Imagine Dr. Peterson working as a psychologist at Arkham Asylum, where Joker spends most of his time when he’s not killing people. If Joker was Jordan Peterson’s patient, how would the real-life psychologist analyze the fictional psychopath?

The Killing Belief

First of all, Dr. Peterson would diagnose Joker with a severe case of nihilism. The dictionary defines nihilism as a rejection of “moral principles, in the belief that life is meaningless.” Peterson identifies nihilism as one of the roots of much evil.

In his bestselling book 12 Rules for Life, Peterson wrote that suffering leads some to believe that life is a “joke being played on us.” This makes them resentful toward society, life, even existence itself. For some, this worldview has motivated “mass murder, often followed by suicide.”

For example, Peterson noted that nihilism and resentment motivated Eric Harris, one of the perpetrators of the Columbine High School massacre of 1999. Harris and his partner murdered ten fellow students before killing themselves. The day before the massacre, Harris demonstrated his nihilism when he wrote in his journal:

It’s interesting, when I’m in my human form, knowing I’m going to die. Everything has a touch of triviality to it.

And his overwhelming resentment was on display when he wrote:

“I hate you people for leaving me out of so many things (…) You had my phone, and I asked you and all, but no, no no don’t let that weird looking Eric kid come along I HATE PEOPLE and they better . . . fear me.”

Suffering leads some to embrace nihilism and resentment. And some have used their nihilism and resentment as excuses for monstrous acts.

In The Killing Joke, that is exactly what the Joker did. He used his “one bad day” as an excuse to embrace nihilism and wallow in resentment. He proclaimed:

It’s all a joke! Everything anybody ever valued or struggled for… It’s all a monstrous, demented gag!

Joker also ranted about “life, and all its random injustice” and “the inescapable fact that human existence is mad, random and pointless.” He deliberately chose to go insane, because, “In a world as psychotic as this… any other response would be crazy!”

Joker tried to justify his choice by performing a monstrous experiment. He tried to drive an ordinary man insane by giving him his own “one bad day.” He kidnapped Police Commissioner James Gordon and gave him the worst day of his life. (I’ll spare you the gruesome details.) He wanted to “prove a point”: that the only response to the tragic comedy of life was nihilism and madness.

Everyday Heroes

But Peterson would tell Joker he’s wrong. Ordinary people can maintain morality and sanity even in the face of tragedy. Indeed ordinary people do so every day. As Peterson wrote:

I knew a man, injured and disabled by a car accident, who was employed by a local utility. For years after the crash he worked side by side with another man, who for his part suffered with a degenerative neurological disease. They cooperated while repairing the lines, each making up for the other’s inadequacy. This sort of everyday heroism is the rule, I believe, rather than the exception.

In The Killing Joke, Commissioner Gordon also proved Joker wrong. In spite of being tortured physically and emotionally, Gordon retained not only his sanity but his high ethical standards. After Batman rescued him, Gordon insisted that Joker be arrested “by the book” (legally). Even after everything he went through, Gordon did not fall into overwhelming resentment against the world, or even his tormentor. He held firmly to his code and called, not for vengeance, but for justice and the rule of law.

When Batman confronted Joker, he reported his failure to him.

Incidentally, I spoke to Commissioner Gordon before I came in here. He’s fine. Despite all your sick, vicious little games, he’s as sane as he ever was. So maybe ordinary people don’t always crack. Maybe there isn’t any need to crawl under a rock with all the other slimey things when trouble hits. Maybe it was just you, all the time.

According to Batman, ordinary people can turn away from the dark path of nihilism and resentment, even in the face of tragedy. Jordan Peterson would agree. He wrote:

Some people degenerate into the hell of resentment and the hatred of Being, but most refuse to do so, despite their suffering and disappointments and losses and inadequacies and ugliness, and again that is a miracle for those with the eyes to see it.

A Real-Life Super-Hero

Everyday heroism is indeed miraculous. And yet the human spirit is capable of even more. For example, Peterson wrote of the famous Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who:

…had every reason to question the structure of existence when he was imprisoned in a Soviet labour camp, in the middle of the terrible twentieth century. (…) He had been arrested, beaten and thrown into prison by his own people. Then he was struck by cancer. He could have become resentful and bitter. (…) But the great writer, the profound, spirited defender of truth, did not allow his mind to turn towards vengeance and destruction.

Instead of taking the path of nihilism and resentment, he chose the path of self-improvement, even while sick and imprisoned. That path led him to write a book about the horrors of the Soviet prison system called The Gulag Archipelago. This book was so powerful, so influential, that it contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Empire. Russia still has political prisoners suffering abuse, but probably far fewer thanks to Solzhenitsyn.

Such a heroic response to tragedy would baffle Joker. In The Killing Joke, he said he could tell that Batman must have also had his own “one bad day.” So why, he asked, didn’t Batman “get the joke” of life? “Why aren’t you laughing?” Joker demanded.

“Because I’ve heard it before,” Batman answered, “and it wasn’t funny the first time” (and then threw Joker through a funhouse mirror).

As we all know, Batman did have “one bad day.” When he was a child, his parents were murdered right before his eyes. But unlike Joker, he refused to give in to resentment and hatred. Like Gordon, he retained his human decency. And he went even beyond that. Like Solzhenitsyn, he held himself to even higher moral standards and heroically saved others from suffering the kind of tragedy that he suffered.

Responsibility Is the Key

What’s the difference between Batman and Joker, between Solzhenitsyn and the Columbine killers? Why does suffering turn some people toward heroism and others toward monstrosity?

The biggest difference is responsibility.

Eric Harris surely had to endure some suffering and injustice, perhaps especially at school. But rather than assume any responsibility for his situation, he chose to place all the blame on others.

And Joker’s “one bad day” was largely of his own making. But he took no responsibility for it. Instead, he blamed “the world” and chose insanity as way to suppress such memories altogether.[1]

Batman had a much better excuse to not take responsibility for his own “one bad day.” After all, he was only a child when his parents were murdered. But he assumed responsibility anyway. The memory of that night drove him to do his utmost to save others from such a tragedy.

Solzhenitsyn had a similar response to tragedy. While unjustly imprisoned, he also had a plausible excuse to only think of himself as a victim. Instead, he embraced a level of responsibility many would consider extreme. As Peterson wrote:

During his many trials, Solzhenitsyn encountered people who comported themselves nobly, under horrific circumstances. He contemplated their behaviour deeply. Then he asked himself the most difficult of questions: had he personally contributed to the catastrophe of his life? If so, how? He remembered his unquestioning support of the Communist Party in his early years. He reconsidered his whole life. He had plenty of time in the camps. How had he missed the mark, in the past? How many times had he acted against his own conscience, engaging in actions that he knew to be wrong? How many times had he betrayed himself, and lied? Was there any way that the sins of his past could be rectified, atoned for, in the muddy hell of a Soviet gulag?

Solzhenitsyn pored over the details of his life, with a fine-toothed comb. He asked himself a second question, and a third. Can I stop making such mistakes, now? Can I repair the damage done by my past failures, now?

That was the mindset that empowered him to not only survive but to change the world.

The Choice

To return to the original question, what does it take to turn an ordinary person into a monster?

“One bad day” is Joker’s answer. But he’s only partly right. As Jordan Peterson tells us, it all depends on how one responds to tragedy and suffering.

If a person responds by fleeing responsibility, by sinking into nihilism and resentment, that can indeed lead to monstrous acts that perpetuate tragedy. Even if it doesn’t get that bad, that path can still make ordinary people miserable.

But if we respond by embracing responsibility, we can help prevent unnecessary tragedy and find true meaning in life.

Responsibility is what it takes to turn an ordinary person into a hero.

[1] In The Killing Joke, Joker said:

Remember? Ohh, I wouldn’t do that! Remembering’s dangerous. I find the past such a worrying, anxious place. (…) So when you find yourself locked onto an unpleasant train of thought, heading for the places in your past where the screaming is unbearable, remember there’s always madness. Madness is the emergency exit. You can always step outside, and close the door on all those dreadful things that happened. You can lock them away forever.

Jordan Peterson would tell Joker that was a bad idea. As he wrote:

Memory is a tool. Memory is the past’s guide to the future. If you remember that something bad happened, and you can figure out why, then you can try to avoid that bad thing happening again. That’s the purpose of memory. It’s not “to remember the past.” It’s to stop the same damn thing from happening over and over.

Recurring memories are trying to teach us something. If, like Joker, we run away from bad memories, especially ones fraught with guilt, we can never learn their lessons.

Originally published at The Future of Economic Education.